Introduction

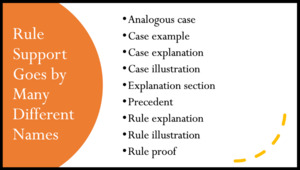

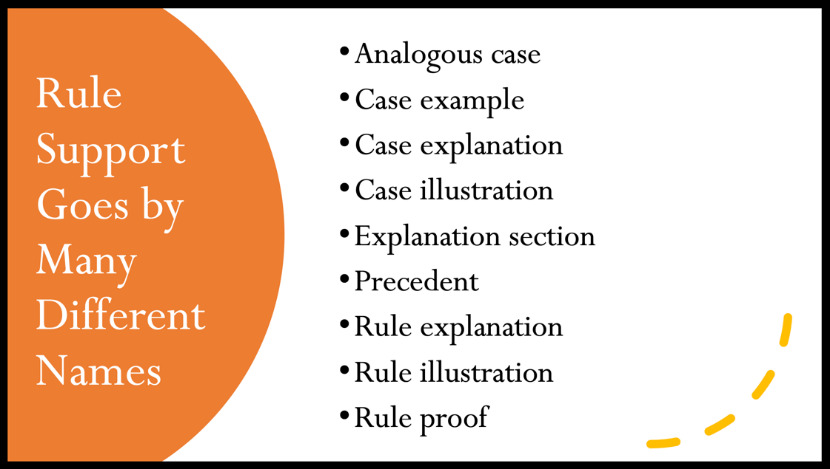

There is a lack of uniformity regarding how law professors address the rule support section, sometimes called case illustrations, rule explanations, rule proof, or a variety of other terms. This broad variance is not limited to the wide array of terminology used to describe this section. Rather, this divergence relates to a fundamental understanding of the meaning and role of the rule support section.

For example, a first-year student in one law school may learn that the rule support section of the IRAC paradigm illustrates the meaning of a rule by providing the facts, holding, and often reasoning of a previous case or cases that address the same issue. However, a student in a different law school may not learn about the rule support section at all. Rather, the student may learn about some rule support concepts, but these ideas will be included in a discussion of the rule section, not the rule support section. A law student in a third law school may learn that the rule support section encompasses both the rule and the rule support section (and maybe even the issue statement as well). When all three students arrive at the same summer internship and attempt to have a thoughtful discussion of how to structure their legal analysis for an assignment, they may each have a very different approach.

In addition to the different conceptualizations of the rule support section that different law students are learning, students are also being confronted with different terminology to simply name the rule support section. For instance, a student may learn about “rule support cases” in her legal writing class, hear about “rule explanation” during a session with academic success, and be asked about “case illustrations” during her individual meeting with the writing specialist. This discrepancy is not limited to first-year academic experiences—the student may be asked about “rule proof” at a law firm internship, “analogous cases” at a judicial externship, and “case explanation” in her clinic.

These examples illustrate a paradox. Despite being theoretically and practically important to legal analysis,[1] the rule support section often does not get the scholarly focus or interest that it deserves compared to other parts of the IRAC paradigm. My empirical analysis of the fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks found that these textbooks name, conceptualize, and describe the rule support section of the IRAC paradigm in very different ways and in vastly differing depths. This wide variance may be indicative of a wider disagreement among legal writing professors regarding the rule support section. Also, this array of approaches is a distinct contrast from how professors and practitioners approach the other components of the IRAC paradigm—the issue, rule, application, and conclusion—which are referred to only by those exact terms[2] and are defined in consistent ways.[3]

To be clear, in my conceptualization, the rule support section uses a prior case or cases to illustrate how the courts have previously applied the relevant rule, but it does not encroach on or even wade into either the rule or the application part of the IRAC structure.[4] The role of the rule support section is to provide one or more concrete case examples to set up the analogical reasoning in the application section by giving meaning to the broad, general rules.[5] Therefore, the rule support section provides a “bridge” between the rule and the application.[6]

This Article explores how the fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks approach the rule support section, focusing on how they present various aspects of the rule support section in similar or, for the most basic and fundamental questions, in different ways. The goal of this Article is to find the common ground as well as the differences across approaches to the rule support section to figure out how to address these variances in our legal writing classrooms. In addition, this Article raises the issue of whether legal writing textbooks are spending sufficient space explaining the rule support section.

In Part I, this Article discusses the basic IRAC paradigm, the concept of analogical reasoning, the importance of the rule support section, and the way that the rule support section is used in practice by judges and advocates. In Part II, this Article describes my methodology for defining, selecting, collecting, and analyzing the legal writing textbooks that I studied.[7] In Part III, this Article explores the results of my empirical analysis and compares various aspects of how legal writing textbooks approach the rule support section. This part delves into the areas where the textbooks diverge in their approach to the rule support section, including the basic questions of how much each textbook discusses the rule support section, how to refer to this part of the IRAC structure, how to conceptualize this section, and what to include in this section. This Part also identifies areas of agreement, but these concern less fundamental instructional points that many textbooks do not actually address. Finally, in Part IV, this Article discusses the pedagogical implications of this empirical analysis, including how legal writing professors may take a textbook’s approach to rule support cases into account when deciding which textbook to use and how legal writing professors may be able to prevent confusion in their classrooms. This section also suggests that some legal writing textbooks may want to discuss the rule support section in additional detail.

I. The Role of the Rule Support Section in the IRAC Structure

The IRAC paradigm is the basic organizational scheme for legal analysis. It instructs a legal writer to include the issue, the rule, the application, and the conclusion. Each of these parts is uniformly defined and understood, and legal writing textbooks discuss the rule and the application sections extensively.

In addition, analogical reasoning is a staple of legal analysis. Lawyers and law students use this type of reasoning to predict what a court will do, or advocate for what a court should do, by comparing a new fact pattern with a previous case or cases with the identical issue.

The rule support section is a pivotal part of the IRAC paradigm, setting up the application section by providing concrete factual details and the related holding and reasoning to compare to the new fact pattern using analogical reasoning. Accordingly, the rule support section creates a bridge between the rule and the application. Also, judges and lawyers use rule support cases frequently in their legal analysis.

A. The IRAC Structure

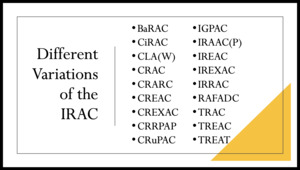

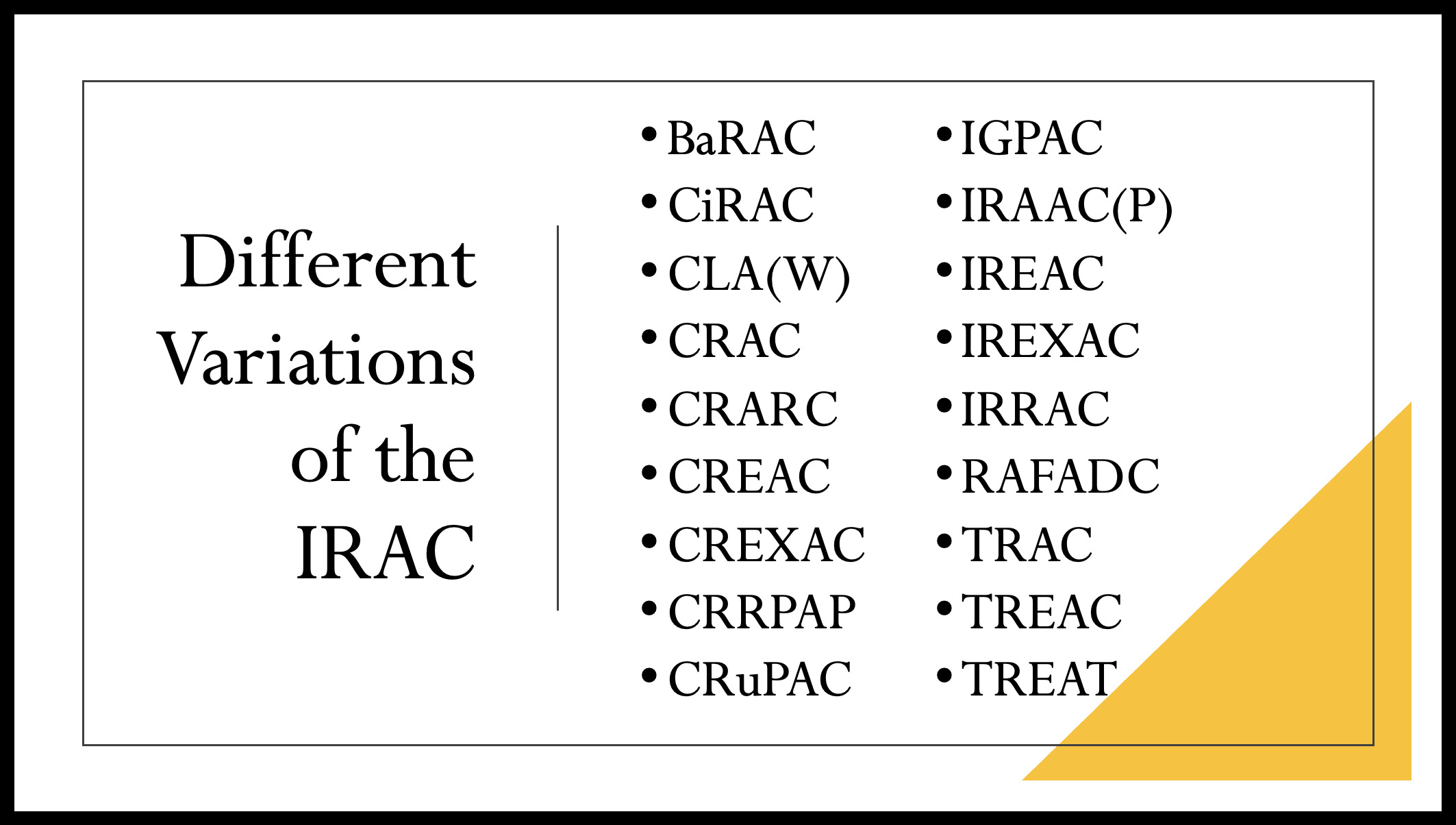

The IRAC or CRAC legal writing paradigm[8] is the basic organizational scheme for legal analysis.[9] The paradigm is also often called IREAC, CREAC, or a variety of other acronyms.[10] Law students learn this structure as the starting place for thinking through and organizing their analysis.[11] Although some scholars are either tepid supporters or active critics of the IRAC paradigm,[12] it remains a useful tool to teach the basics of legal writing, organization, and analysis to new legal writers because it sets up the syllogistic structure of “effective” legal reasoning.[13] It is particularly helpful when students understand that the structure is “a tentative, flexible, adaptable framework” that students can tweak, alter, or potentially even abandon once they truly comprehend legal analysis.[14]

Specifically, the IRAC paradigm is based on deductive reasoning, which starts with a general proposition and ends with a specific conclusion.[15] It involves creating a syllogism to connect two true premises—the major premise and the minor premise—to reach a conclusion that should therefore also be true.[16] A frequently used example is:

Major premise: All men are mortal.

Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.[17]

In the IRAC structure, the major premise is the rule, the minor premise is the application, and the conclusion is the conclusion.[18] Notice that this paradigm, like some of the variations of the IRAC structure, includes no letter or step for the rule support part of the analysis.[19]

According to Brian N. Larson, this deductive argumentation scheme, when applied in the context of legal analysis, looks like:

Major premise: According to legal authority J, in every instance with features ƒ1 . . . ƒn, legal category A applies.

Minor premise: The instant case has features ƒ1 . . . ƒn.

Conclusion: Legal category A applies in the instant case.[20]

Some legal writing professors distinguish between the IRAC and CRAC versus the IREAC and CREAC structures.[21] These professors use IRAC or CRAC as the appropriate paradigm for rules-based reasoning and IREAC or CREAC as the correct structure when the writer’s legal analysis requires a rule support section. I use the two groups of acronyms synonymously and do not distinguish the IRAC, CRAC, IREAC, and CREAC structures from one another, and I will take that approach in this Article.[22] However, it is worth reiterating that the basic IRAC structures fail to include a letter to explicitly refer to the rule support section[23] although many professors and practitioners treat the rule support section as a part of the “R” for the rule section.[24]

In her empirical analysis, Tracy Turner collected and analyzed thirty legal writing textbooks and forty-seven law review articles about the IRAC paradigm.[25] Turner listed the alternative acronyms that she discovered in her review of these sources as well as their meanings.[26] Based on this analysis, Turner concluded that, despite disagreeing about whether to begin with the issue or with the conclusion and where to address policy, the different IRAC varieties were “more detailed” but not “inconsistent” with the basic IRAC structure.[27] The differences between the acronyms “relate more to substance than to organization,” demonstrating “the need to explain and illustrate the rules through discussion of case examples, the need to base conclusions on comparisons between the case at hand and the precedent cases, and the need to address counterarguments.”[28]

Looking at the IRAC structure, law professors and practitioners take a fairly uniform approach to the issue, the rule, the application, and the conclusion sections. The “issue” is generally defined as the legal question that the writer is answering.[29] Depending on a writer’s preferred acronym for the legal paradigm, the writer may start instead with a “conclusion” or a “thesis,” which is uniformly considered to be the answer to the issue.[30] The “rule” section is generally seen as setting forth the legal requirements that govern the relevant issue.[31] The “application” section is conceptualized as the portion of the paradigm where the writer applies the rule to the facts of the client’s case.[32] Finally, the “conclusion” is generally defined as the answer to the issue.[33] Before my empirical research, my impression was that the rule support section is the portion of the IRAC paradigm that is treated the least consistently in the classroom and in practice. One of the goals of my empirical analysis was to determine whether this intuition was accurate.

In addition, first-year legal writing textbooks tend to address the rule section[34] as well as the application section[35] of the IRAC paradigm at length, often devoting at least a whole chapter or subsection of a chapter to these sections and discussing these general concepts throughout the textbook. The textbooks also discuss the issue[36] and the conclusion.[37] However, because these sections are generally shorter and simpler than the rule and application sections, they are often discussed in much less detail. In conceptualizing this research project, I wondered whether legal writing textbooks address the rule support section in as much detail and depth as they address the rule and application sections.

B. Analogical Reasoning in the Law

“Law is created by evaluating the litigant’s story against something outside itself,” including against one or more rule support cases.[38] The theory is that all new cases “must be judged by external criteria that offer some assurance of a result that is reasoned, fair, [and] functional.”[39] If the new fact pattern and the previous case facts are similar and the similarities are legally relevant, then a court should reach the same result in the new case.[40] If the new fact pattern and the previous case facts are different and the differences are legally relevant, then the court should reach the opposite result in the new case.[41]

This type of reasoning is analogical reasoning. Lawyers employ analogical reasoning “daily” to determine what a court will likely conclude and to argue what a court should conclude.[42] Analogical reasoning supports a conclusion or an argument by demonstrating relevant factual similarities or differences between a new fact situation and a previous case or cases.[43]

Returning to Larson’s argumentation scheme, the pattern for analysis by legal analogy looks like:

Major premise: Legal category A applied to cited case, and cited case had features ƒ1 . . . ƒn.

Minor premise: Instant case has features ƒ1 . . . ƒn.

Conclusion: Legal category A applies to instant case.[44]

As another potential variation illustrating analogical reasoning, Mary Beth Beazley suggests revising the Socrates syllogism as follows to track the IREAC format, rather than the IRAC format:

Issue: Is Socrates mortal?

Rule: All human beings are mortal.

Explanation: Human beings include men and women.

Application: Socrates is a man.

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.[45]

A rule support case or multiple rule support cases can illustrate that human beings include men and women.

First-year law students learn about analogical reasoning in many, if not most, of their courses.[46] In addition, first-year legal writing textbooks address analogical reasoning in detail.[47]

Some scholars argue that arguments based on analogical reasoning are either not as strong as other forms of reasoning or are not logically valid at all.[48] However, many judges, scholars, and commentators believe that analogical reasoning “lies at the core of the common-law process.”[49] They assert that the “very idea” of analogical reasoning is “distinctively legal reasoning.”[50] Although this type of reasoning is also applied in different fields and disciplines, it is “central to legal reasoning, legal argument, and legal justification.”[51]

Lawyers are trained to possess the “legal experience and expertise” to employ analogical reasoning when addressing legal issues.[52] Because there are a “virtually infinite number of similarities and differences between any two items,” different individuals with different experiences and training will find a range of similarities and differences between the two items.[53] Lawyers, however, are more likely to spot relevant connections based on relevant “legal categories” that go “beyond the appreciation of the nonexpert,” and, therefore, analogical reasoning in the law may be different from and more important than analogical reasoning in other areas and fields.[54]

Analogical reasoning is the basis for the inclusion of the rule support section in the IRAC paradigm—the rule support section sets up the analogical reasoning in the application section. In the application section, a legal writer compares and contrasts the legally-relevant aspects of one or more rule support cases with the new fact pattern. However, this type of analysis would often be illogical without the rule support section bridging the rule section and the application section.[55]

The need for rule support cases to set up analogical reasoning is a contrast with legal issues where the rule on its own answers the relevant legal question. In that situation, a writer should apply rule-based reasoning to address the relevant legal issue because the “express language” of the rule of law provides the required answer to the legal question.[56] There are also other times when a court will apply policy-based reasoning, consensual normative reasoning, or narrative reasoning.[57] In these situations, the rule support section may not be as pivotal or even necessary to the legal analysis.

C. The Importance of the Rule Support Section

The rule support section is often a pivotal part of the success of a legal writer’s analysis. This section provides the basis for a legal writer’s analogical reasoning—it sets up the application section by providing concrete factual examples that the writer will compare to the relevant portions of the new fact scenario.[58] In other words, this step of the legal analysis paradigm provides a “bridge” between the rule and the application.[59]

The rule support section is frequently the “cornerstone” of the entire IRAC structure.[60] In these situations, the rules do not provide the writer with a sufficient basis to analyze the relevant issue because the rules are broad and vague.[61] The legislature passing or the courts writing and refining these rules intentionally chose language that was broad enough to address unknown future factual situations.[62] In these scenarios, a writer simply cannot get from the rule to the application section without the rule support case or cases to set up the application section.[63] In addition, rule support cases represent mini-stories that humanize the law and make it much more understandable, rather than just an amorphous and general rule.[64]

To be clear, a writer does not always need to use a rule support case or rule support cases to set up the application section.[65] For instance, sometimes the rule itself is straightforward and answers the relevant legal question.[66] In that situation, the author is able to employ rule-based reasoning alone to address the relevant issue.[67] Alternatively, sometimes an issue presents a purely legal question and therefore the client’s specific facts are irrelevant.[68] In that case, once the writer states the relevant rule or argues what the correct rule should be, the writer can simply apply the rule to the relevant parts of the fact pattern.[69]

A legal writer’s use of rule support cases will vary depending on the relevant cases and fact pattern.[70] Among other questions, a writer must determine whether to include a rule support section at all; which rule support cases to use; how many rule support cases to include; in what order to present them; how much detail to go into for the rule support case’s facts, holding, and reasoning; and whether to use an explanatory parenthetical instead of a full rule support paragraph. The right approach to these questions often varies greatly depending on the context and the relevant legal issue. In conceptualizing this research, I wondered whether first-year legal writing textbooks sufficiently address these fundamental aspects of drafting the often critically important rule support section.

D. Judges’ and Lawyers’ Use of Rule Support Cases

In addition to being an important part of the IRAC structure in theory, the rule support section is also an important part of legal analysis in practice.[71] Judges and lawyers frequently use rule support cases to set up the analogical reasoning in their application.[72]

In a recent empirical study of judicial opinions and party briefs, Larson demonstrated that judges and practitioners often include rule support cases in their legal analysis.[73] Larson conducted the study to determine the norms of how judges and lawyers actually use cases, not just how lawyers should use cases.[74]

To make up his data set, Larson randomly selected 55 reported and dispositive opinions issued by federal district courts.[75] He then collected the 144 party briefs that led to the relevant 55 court opinions, for a total of 199 artifacts.[76] Next, Larson broke the 199 artifacts down into 1,810 distinct argument segments and coded each case cited within an argument segment as a case use.[77] Because judges and lawyers use cases to support statements about legal rules, to illustrate how the legal rules are used in other cases, to provide policy reasoning, to generalize about previous cases, and to support quotations from a cited case, Larson coded each case use for one or more of these categories of uses, depending on which use applied.[78]

Larson coded a case as “EXAMPLE” if the author cited the case as an example of another case “in this body of law” and included the example case’s facts, holding, or both or explicitly or implicitly compared the facts of the example case with the facts of the case involved in the motion or opinion.[79] Case discussions that started with “In [fill in case name] . . .” were usually coded as “EXAMPLE,” but this formula was not required.[80]

Larson found that lawyers and judges used cases in some ways more than others.[81] Although the opinions and briefs used cases as rules and quotations twice as often they used cases as rule support cases, the judges and advocates used cases for rule support twice as often as they used cases for policy arguments and even more than twice as often as they used cases for generalizations.[82] Interestingly, lawyers used cases as rule support cases more often than judges used cases in the same way.[83]

Also, Larson found that prevailing attorneys used rule support cases in their briefs more than the non-prevailing attorneys used rule support cases.[84] This difference was “practically and statistically” significant.[85]

Larson’s research demonstrates that practitioners and the courts (although less often than practitioners) use the rule support section as an important part of their legal analysis paradigm to set up the analogical reasoning in their application. The rule support section is thus often a pivotal analytical step in both theory and in practice.

II. Methodology

I employed a relatively simple and straightforward methodology to identify and analyze the fifteen first-year legal writing textbooks that I consider in this Article. I aimed to create a non-experimental design to “merely study the world as you find it” by gathering and analyzing existing legal writing textbooks.[86] To complete this task, I identified the fifteen legal writing textbooks that appear to be the most widely used. I then manually reviewed and coded aspects of the selected textbooks for any mention of the rule support section using any of the many possible terms employed to describe this section.[87]

A. Selecting the Data Set

To gather information about how the rule support section is taught, I set out to identify the most popular first-year legal writing textbooks. I defined first-year legal writing textbooks as the legal writing textbooks written for group instruction to first-year law students who are taking Legal Research and Writing. These textbooks are designed to teach the “basics of legal writing.”[88] While they do not need to be read from beginning to end, the textbooks are designed to be “comprehensive,” providing a “form of one-stop shopping.”[89] I included textbooks that teach just predictive writing as well as textbooks that teach both predictive and persuasive legal writing.[90]

I limited my search to textbooks whose latest edition was published over the 10-year period from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2023.[91] For books with multiple editions, which applies to most of the textbooks on my final list, I reviewed the most recent edition available.[92] I also limited the data set to only print textbooks.[93]

Of course, my search parameters excluded many types of legal writing textbooks. For example, I excluded all legal writing books that were written for undergraduate students, prospective law students, LL.M. students, paralegals, practicing attorneys, or aspiring judges or law clerks as well as any textbooks that focus primarily on legal research or legal citation, rather than legal writing. I intentionally left out all specialized legal writing textbooks, including general writing guides, style manuals, grammar textbooks, editing guides, legal writing hornbooks, and books on the ethics of legal writing.[94] I also excluded specialized textbooks that focus only on writing legal memoranda, exam writing, persuasive writing, contract drafting, written and oral appellate advocacy, scholarly writing, bar exam question writing, litigation document drafting, legislative drafting, drafting wills, or judicial opinion writing. I kept out legal writing exercises or case files, “shortened” or “in a nutshell” legal writing books, supplemental legal writing textbooks, reference books, writing advice from judges, legal dictionaries, and legal thesauruses.

I started compiling my list of textbooks that met my criteria by searching Brooklyn Law School’s library catalogue and the WorldCat library catalogue, which formed the backbone of my search. The WorldCat library catalogue is the “‘world’s largest library catalogue.’”[95] It offers access to the collections from more than 10,000 libraries, including 405 million books and 43 million e-books.[96] I used the subject tag “legal composition,” filtered for “print book” and a publication year between 2014 and 2023, and reviewed those results. I also searched for legal writing textbooks on the websites of legal academic publishers, including Aspen Publishing, Carolina Academic Press, and West Academic Publishing.[97]

Following the approach that Alexa Z. Chew took to determine popularity in her empirical study of legal style books in The Fraternity of Legal Style, I used WorldCat to narrow the data set of first-year legal writing textbooks to only the most popular textbooks.[98] Sales data for books is generally not available from book publishers and retailers.[99] Therefore, I used the number of libraries that held a copy of any edition of each first-year legal writing textbook, both print copies and eBooks, as an indicator of the textbook’s popularity.[100]

Here is a chart of the fifteen first-year legal writing textbooks that I included in the data set, ranked from most to least popular based on WorldCat library holdings as of May 15, 2024:

I eliminated from the final data set any textbooks that were not held in at least 100 libraries according to WorldCat.[101]

B. Review of the Data Set

Because this empirical analysis focuses on the importance of the rule support section in the IRAC paradigm, I drafted the research questions to cover a comprehensive list of potential subjects that a first-year legal writing textbook or a legal writing professor might address related to the rule support section. A textbook that answers all these questions in detail should effectively and thoroughly cover the rule support section and rule support cases. Therefore, the empirical analysis aimed to answer the following research questions:

-

How much space and attention do legal writing textbooks devote to the rule support section? Specifically, which chapters address the rule support section? At one end of the spectrum, are there entire chapters devoted just to the rule support section? Or, at the other end of the spectrum, do authors just mention this section in passing?

-

What terminology does each legal writing textbook use to describe the rule support section or rule support cases, and do they always use the same terminology throughout the textbook?

-

How do legal writing textbooks define the rule support section?

-

How do legal writing textbooks describe the purpose of the rule support section?

-

According to legal writing textbooks, which components should a rule support case discussion include and in what order?

-

When do legal writing textbooks suggest that legal writers include a rule support section?

-

How do legal writing textbooks suggest that legal writers select the most effective rule support cases to include?

-

How many rule support cases do legal writing textbooks suggest that legal writers should include?

-

What do legal writing textbooks advise legal writers regarding the proper order to present rule support cases in?

-

What do legal writing textbooks recommend as the most effective length of each rule support case?

-

How do legal writing textbooks suggest that legal writers write about rule support cases?

-

How do legal writing textbooks instruct legal writers to use explanatory parentheticals in the rule support section?

-

Do legal writing textbooks suggest that rule support cases should be treated differently in different contexts?

Based on these research questions, I reviewed each textbook for any mention of any terminology that might refer to the rule support section. Accordingly, the potential terms included “analogous case,” “case illustration,” “case example,” “case explanation,” “rule explanation,” “explanation of rule,” “rule illustration,” “rule proof,” “proof of rule,” “rule proof and explanation,” “rule support,” or “precedent” in the appropriate context. Even if the textbook writer or writers did not use this exact terminology, I looked for any discussion of the ideas describing and concepts supporting the rule support section, especially in the textbooks where the authors did not explicitly discuss rule support cases.

I did not, however, focus on ideas that are potentially or peripherally related to the rule support section unless a textbook explicitly connected the discussion of these ideas to the rule support section. For instance, most textbooks address the conceptualization of the rule section and the application section of the IRAC, analogical reasoning in general,[102] legal writing advice, citation, and other topics that have an indirect or peripheral connection to the rule support section. If the textbook author or authors did not explicitly tie these concepts to the rule support section or comment specifically on the rule support section, I did not include those ideas in my analysis.

Once I identified the relevant paragraphs, sentences, or even phrases from the textbooks, I sorted the relevant text into one or multiple relevant categories. To match the research questions, the categories included (1) the chapters or topics where the rule support section is discussed; (2) the terminology used; (3) how the rule support section is defined; (4) how the rule support section’s purpose is described; (5) the parts of each rule support case; (6) the order that the parts of each rule support case should be presented in; (7) when a legal writer needs to include a rule support section; (8) how a writer should select which rule support case or cases to use; (9) how many rule support cases a writer should include; (10) the order to present rule support cases in; (11) the suggested length of each rule support case; (12) how a writer should write about a rule support case or cases; (13) how to use explanatory parentheticals for rule support cases; (14) the different treatments of rule support cases in different contexts; and (15) a catch-all for any other observations.[103]

III. An Empirical Analysis of Legal Writing Textbooks

The fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks take a variety of different approaches to some of the most fundamental questions about the rule support section that I identified in my research questions. These questions include the proper nomenclature for the rule support section, the definition of the rule support section, the purpose of the rule support section, and the components of each rule support case.

At the same time, the first-year legal writing textbooks that address other, less central rule support topics employ a more uniform approach. This consistency may arise, at least in part, because fewer textbooks discuss some of these subjects. The answers to these research questions are not nearly as fundamental to teaching about rule support cases and the rule support section as the issues on which the textbooks diverge. Likely because these questions are not as fundamental to understanding the rule support section, fewer textbooks address each issue.

A. Diverse Approaches

My main conclusion is that the first-year legal writing textbooks in this empirical analysis do not take a consistent approach to multiple aspects of rule support instruction, and these aspects involve some of the most basic and fundamental questions about the rule support section. The textbooks diverge on the amount of space and attention devoted to this section, the terminology used to discuss this section, the definition of what this section means, the purpose of this section, and what parts to include in this section and in what order.

1. Depth of Treatment

The textbooks’ depth of discussion regarding the rule support section varies greatly. Some textbooks discuss the rule support section over many pages and in multiple chapters, covering the subject in detail and answering most if not all of my research questions.[104] Other textbooks mention the rule support section only briefly, often missing aspects of what students need to learn about this section.[105] The majority of textbooks are in between these two extremes—discussing the rule support section in detail but not answering some of the questions for which I was coding.

A few textbooks covered the rule support section and rule support cases with a detailed and nuanced approach that answers most if not all of the questions I was coding for.[106] For instance, in The Mindful Legal Writer: Mastering Predictive and Persuasive Writing, Heidi K. Brown goes into a lengthy and involved discussion of both rule support cases and the rule support section in multiple chapters.[107] In particular, she addresses rule support cases, the rule support section, or both in the introduction and in chapters about reading and briefing cases, single-issue and multiple-issue office memoranda, legal citation, receiving writing feedback, self-editing, persuasive letters, persuasive motions, trial-level briefs, appellate briefs, and oral argument.[108] In these chapters, Brown provides detailed descriptions, formulas, examples, and checklists.[109]

Similarly, in The Legal Writing Handbook: Analysis, Research, and Writing, Laurel Currie Oates, Anne M. Enquist, and Jeremy Francis discuss rule support cases in a multitude of chapters.[110] The authors address the rule support section in the very first chapter introducing the student to law school.[111] In this 963-page textbook, they also discuss the rule support section in many additional chapters, including in chapters on mandatory versus persuasive authority; reading cases; research tools and effective research strategies; drafting memoranda, including how to structure a discussion section with an elements analysis, a factor analysis, or a balancing of competing interests analysis; drafting e-memoranda; drafting motion briefs; drafting appellate briefs; revising, editing, and proofreading; effective writing, including words, sentences, paragraphs, and the entire document; preparing for and delivering an oral argument; grammar; and legal writing for English-as-a-second-language writers.[112]

These textbooks are not the only textbooks to spend a considerable amount of time and effort describing the rule support section. In many textbooks, the author or authors include an entire chapter, sub-chapter, or significant portion of a chapter devoted just to the rule support section.[113] The textbooks also address the rule support section in many additional chapters as well.

In contrast, in Legal Writing and Other Lawyering Skills, Nancy L. Schultz and Louis J. Sirico, Jr. do not explicitly address the concept of the rule support section.[114] In fact, when the authors first introduce the IRAC structure, they state that it includes only the issue, rule, application or analysis, and conclusion; they do not mention the concept of the rule support section at all.[115] The textbook does allude to the concept of the rule support section but never explicitly states that it has its own name or role in the IRAC structure.[116] For instance, in a checklist of information that “any good legal analysis must contain,” the authors note that the writer must “[d]iscuss the facts, holdings, and rationales of all important relevant cases,” but the authors do not state that this information is part of the rule support section.[117] The textbook also includes multiple examples of rule support cases without labeling them as their own specific section of the IRAC structure.[118] The authors do discuss some of the questions that I analyzed, but none of this information is stated specifically with reference to rule support section.[119]

Similarly, in A Practical Guide to Legal Writing and Legal Method, John C. Dernbach, Richard V. Singleton II, Cathleen S. Wharton, and Catherine J. Wasson describe the idea of rule support cases but do not make them their own section.[120] Instead, the authors include them as a part of a larger rule section.[121] The textbook addresses some of the issues that I coded for but these statements are not specific to the rule support section. Instead, they are a general “explanation” of the law in the rule section.[122]

2. Terminology

The fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks do not use the same terminology to consistently refer to the rule support section or the rule support cases.[123] The textbooks’ terminology choices demonstrate multiple different types of inconsistency—inconsistency in the terminology across the textbooks, lack of any terminology to discuss the rule support section in individual textbooks, and inconsistency within some individual textbooks.

Inconsistency Across Textbooks. The textbooks call this section of the IRAC paradigm many different names, including analogous case, case illustration, case example, case explanation, rule explanation, explanation section, rule illustration, rule proof, proof of rule, rule proof and explanation, and precedent.

The term “rule explanation” is by far the most popular term to describe the rule support section. Six textbooks use the term mostly or always,[124] and six textbooks use the term from once up to a few times.[125] The term “rule support,” which is my preferred term, does not appear in any textbooks. In between, the terms “analogous case,” “case illustration,” “explanation section,” “precedent,” “rule illustration,” and “rule proof” are each used either mostly or always in one textbook.[126] Also, the term “case example” is mentioned once in one textbook,[127] and the term “case explanation” is mentioned once in one textbook and a couple of times in another textbook.[128]

Lack of Specific Terminology. Some textbooks do not use any specific terminology to discuss the rule support section.[129] For instance, in Legal Writing and Other Lawyering Skills, Schultz and Sirico do not explicitly pick a consistent term for the rule support section.[130] In an example IRAC, the authors label the rule support section as simply the “Major Premise: (Relevant legal authority or rule)”[131] but in other examples of rule support cases, the authors do not label them as their own specific section of the IRAC structure.[132]

Inconsistency Within an Individual Textbook. Textbook authors generally have their own clear preference for which term to use to describe the rule support section. Most textbook authors choose one term and use that term exclusively throughout the textbook.[133] Alternatively, many textbooks use one term predominantly but also use additional terms once or twice when introducing the general concept of the rule support section or at other points in their instruction.[134]

However, some textbooks regularly employ a variety of terms or switch between terms.[135] For instance, in Legal Method and Writing, Charles R. Calleros and Kimberly Y.W. Holst employ a variety of terms to refer to the rule support section, but they do not adopt a particular term or even use any term consistently. The authors use the term “rule illustration” a few times;[136] use different terms for rule support cases when labeling examples and in the text, including “[c]ase analysis,” “[i]n-depth analysis,” and “[i]n-depth case analysis”;[137] and use the term “[p]recedent” in a sample outline to label the rule support section.[138] They also acknowledge that other professors may use the terms “rule proof and explanation,” “rule explanation,” and “explanation or proof of the rule.”[139]

Calleros and Holst note that, “[f]or convenience, this book will use the terms ‘light analysis’ and ‘in-depth analysis’ to refer to the opposite extremes” of the depth of analysis “spectrum.”[140] In this context, the authors explain that a legal writer engages in “light analysis” when the writer “simply state[s] a proposition of law and cite[s] to supporting authority.”[141] However, a legal writer engages in “in-depth analysis” when the writer “analyze[s] legal authority more thoroughly, such as by discussing the facts, holding, and reasoning of case law.”[142]

3. Conceptualization

The overall conceptualization of the rule support section is another area that differs widely across first-year legal writing textbooks. This variance manifests itself in both how the textbooks define the rule support section and how they describe its purpose.

Competing Definitions. The textbooks that define the rule support section present four approaches. First, the majority of legal writing textbooks view the section narrowly—as the place to demonstrate the meaning of a rule by providing a summary of the relevant facts, holding, and sometimes reasoning of a case or cases applying the relevant rule.[143] Second, a couple of textbooks define the rule support section more broadly to include both the narrow definition of the rule support section plus at least part if not all of the rule part of the IRAC paradigm.[144] Third, some of these textbooks also include the statement of the issue or the conclusion as a part of the rule support section.[145] Finally, one textbook conceptualizes the rule support section as a part of the larger rule section.[146]

The majority of the textbooks in this empirical study define the rule support section as the part of the IRAC paradigm where a legal writer demonstrates the meaning of a rule by providing a summary of the relevant facts, holding, and sometimes reasoning of a case or cases applying the relevant rule.[147] For instance, in The Mindful Legal Writer: Mastering Predictive and Persuasive Writing, Brown defines the rule support section as the part of the IRAC paradigm where the writer “clearly explain[s] and illustrate[s]” the rule to the reader “through carefully selected case examples.”[148] Similarly, in Legal Writing for Legal Readers: Predictive Writing for First-Year Students, Mary Beth Beazley and Monte Smith explain that, “[w]hether th[e] rules come from statutes or common law, the legal writer almost always uses cases to explain” the rule and to “illustrate[] how [the] rule has been or could be applied.”[149]

Textbooks often contrast the rule section with the rule support section to distinguish what the rule support section is.[150] For example, in A Lawyer Writes: A Practical Guide to Legal Analysis, Christine Coughlin, Joan Malmud Rocklin, and Sandy Patrick note, “While rules explain how courts determine whether a particular standard is met, ‘case illustrations’ show how those standards were met in actual cases” and therefore “rules are generally partnered with case illustrations” but are a separate and distinct part of the IRAC structure.[151]

Similarly, in Legal Writing and Analysis, Michael D. Murray and Christy H. DeSanctis explain that the rule support section must be “distinct” from the rule section.[152] The authors state that the rule section “articulate[s] the legal standards that govern the issue” while the rule support section “facilitate[s] [the] reader’s understanding of how the rule will operate in” the client’s case “by illustrating and explaining how it has worked in prior situations.”[153]

Alternatively, a few textbooks describe the rule support section more broadly, encompassing parts of the rule section.[154] For instance, in Legal Writing and Analysis, Linda H. Edwards and Samantha A. Moppett describe the rule support portion of the IRAC paradigm as the step “explaining where the rule comes from and what it means.”[155] In other words, the “basic” version of the rule support section is complete “[o]nce you have formulated the rule, supported your formulation with citations to authority, and shown how the courts have applied the rule in the past.”[156]

Similarly, in Legal Writing, Richard K. Neumann, Jr., Sheila Simon, and Suzianne D. Painter-Thorne conceptualize rule support as “proof—using authority such as statutes and cases—that the main rule on which you rely really is the law in the jurisdiction involved.”[157] The authors explain that the “reader needs to know for certain that the rule exists in the jurisdiction and that you have expressed it accurately.”[158] In order to accomplish this objective, a writer must “[e]xplain how the authority supports the rule, analyze the policy behind the rule, and counteranalyze reasonable arguments that might contradict your interpretation of the rule” and may include a “subsidiary rule [to] help explain the main rule.”[159]

In addition, at least one textbook uses the term to encapsulate the entire first “half of the [IRAC] paradigm.”[160] In Legal Writing: Process, Analysis, and Organization, Edwards and Moppett conceptualize the rule support section to “state the issue, state the rule [to] govern [the issue], explain that rule, and use case authority to illustrate it.”[161]

These broader conceptualizations are contrasted with the application section, not the rule section, to give them meaning.[162] In Legal Writing and Analysis, Edwards and Moppett explain, “If you keep application out of the spot reserved for [rule support], you will learn what rule [support] is not, which is vital to learning what rule [support] is.”[163] Echoing the same sentiment, Neumann, Simon, and Painter-Thorne in Legal Writing state that “[i]f you were to draw a line across the page” where the writer “stops explaining the law generally and starts applying the law to the facts,” then “at that point, above the line would be rule [support] and below it would be rule application.”[164]

Finally, one textbook views the rule support section as simply a smaller piece of the larger rule section. In A Practical Guide to Legal Writing and Legal Method, Dernbach, Singleton, Wharton, and Wasson explain that in the rule section, a writer should “state the general rule and then describe cases relevant to your conclusion that apply the rule” for common law problems.[165]

Purpose. The overall conceptualization of the purpose of the rule support section is another area that varies widely across textbooks. Given the legal writing textbooks’ different approaches to the definition of this section, it is not surprising to find that the textbooks also describe the purpose of this section in different ways.

A textbook’s conception of the rule support section’s purpose is tied into how the author or authors define the section generally. For the majority of the textbooks, which define the rule support section narrowly, the authors consistently describe the rule support section as a place to “give content to the legal rules” by “examining the facts” of the rule support cases and demonstrating the “types of facts that satisfy or do not satisfy” the relevant rule or rules.[166] The “factually rich illustrations will help the reader understand how the courts are incrementally drawing the line between satisfaction and nonsatisfaction of the legal rule.”[167]

In contrast, the textbooks that have a broader definition of the rule support section also have a broader conceptualization of the purpose of the rule support section. For instance, Neumann, Simon, and Painter-Thorne in Legal Writing note that the goal of the rule support section is to “explain and prove the rule because the reader will refuse to believe you until you establish that the rule really is controlling law and you educate the reader on how the rule works.”[168] This purpose includes proving that “the rule is law in the jurisdiction where the dispute will be decided,” showing that the author stated the rule “accurately,” explaining “how the rule operates,” describing the policy behind the rule, and demonstrating that any counteranalysis is not persuasive.[169]

4. Parts and Organization

The first-year legal writing textbooks that provide instruction about the parts of each rule support case agree on the basic components of this section. However, they provide different prescriptions for execution.

The textbooks that explicitly address this issue agree that, at a minimum, each rule support case should explain (1) the facts of the relevant case, (2) the holding of the relevant case, and (3) if provided, the court’s reasoning supporting its holding in the relevant case.[170] A court does not always provide its reasoning and instead often “simply states the relevant facts and the conclusion that results from those facts.”[171] In that situation, a legal writer will not include a “separate description of the court’s reasoning” but just the facts and holding.[172] However, if a writer has a “good guess at why the court reached its conclusion but the court has not been explicit,” the writer is allowed to include that conjecture as long as he or she indicates that this hypothesis is the writer’s educated guess.[173]

The textbooks that address the proper order of these parts of the rule support case instruct that a writer should follow the exact order of (1) facts, (2) holding, and (3) reasoning.[174] Others suggest that legal writers may flip the order of the reasoning and the holding.[175]

Most of these textbooks advise a writer to start the rule support section with a thesis statement, a topic sentence, or a “hook.”[176] This sentence states the “legal principle” or “new information” about the rule that the rule support case shows, identifies “the crux of why the case is important,” or begins with a “transition sentence that makes it clear you are continuing the same topic.”[177]

Alternatively, according to A Lawyer Writes: A Practical Guide to Legal Analysis, this introductory sentence can state the court’s holding.[178] However, Coughlin, Rocklin, and Patrick acknowledge that starting the rule support case with the court’s holding will create a potential redundancy where the writer may state the holding as both the thesis sentence and as the court’s reasoning.[179] The authors explain that “stating the court’s holding twice is fine” because these sentences at the start and end of the rule support case make “effective bookends that reinforce the point” of the rule support case.[180] However, they caution writers to “avoid sounding repetitious” by not repeating the holding “verbatim” in both sentences.[181]

Some textbooks offer additional variations on the components of the rule support case. For instance, in Legal Writing for Legal Readers: Predictive Writing for First-Year Students, Beazley and Smith note that one of four elements that a reader should be able to “glean” from any rule support case description is the “relevant issue.”[182] Although a legal writer does not have to “devote a sentence” to the element or even state the issue “directly,” legal writers must “[b]e sure that readers can identify which of the case’s many issues and sub-issues” the rule support case is being used to illustrate.[183] Because there is a presumption that “the issues in cases you describe in a given section are situated in the same legal context as the client’s issue,” a legal writer may need to “correct” this assumption if appropriate.[184]

Not surprisingly, the textbooks that have a broader conceptualization of the rule support section include additional pieces in the rule support section of the IRAC paradigm. These textbooks advocate including some combination of statutes, other legal authority, policy, and counteranalysis in this part as well.[185] In Legal Writing: Process, Analysis, and Organization, Edwards and Moppett include the overall issue statement as a part of this section also.[186]

Some textbooks suggest that legal writers end the whole rule support section, but not each individual rule support case, with a “rule summary.”[187] In Legal Writing for Legal Readers: Predictive Writing for First-Year Students, Beazley and Smith note that if the rule support section is “so complicated that readers may have lost track of the rule you are explaining,” the writer may want to “restat[e] the rule in a way that clarifies what facets of the rule are particularly relevant to the client’s case” before beginning the rule application.[188] This rule summary may be needed if the rule support section “includes two or three descriptions of cases in which the rule has been applied” because the “alien facts” from the rule support case “may fill readers’ short-term memory, crowding out the rule itself.”[189] The rule summary should be only one to two sentences.[190] The authors explain that a “good default rule” is to include a rule summary although not every rule support section requires one.[191]

Similarly, in Legal Writing: Process, Analysis, and Organization, Edwards and Moppett suggest that if the rule support section is “long and complex,” it is worth ending the section with “a short summary of its key points.”[192] The authors note that this summary will serve as a “jumping-off point for rule application.”[193]

B. Areas of Uniformity

The fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks are more uniform regarding their approach to some less fundamental questions about the rule support section. The textbooks that discuss the issue tend to similarly confront initial rule support writing decisions, including when to use rule support cases, how to select which rule support cases to use, the most effective number of rule support cases to include, and the best order to present rule support cases in. The textbooks also agree about how to draft the rule support section, including the proper length of each rule support case and how to write about rule support cases, how to use explanatory parentheticals in the rule support section, and the varied treatment of rule support cases in different contexts.

However, only a few textbooks actually address these specific and less fundamental topics. This lack of discussion may explain at least in part why there is more uniformity in the way the first-year legal writing textbooks address these topics.

1. Initial Decisions

The first-year legal writing textbooks take a relatively uniform approach to when to include a rule support section, how to select which rule support cases to include in that section, the right number of rule support cases to include, and what order to discuss those rule support cases in.

When to Include. Most textbooks imply but do not explicitly state when a legal writer should include one or more rule support cases in his or her legal analysis. As a preliminary matter, a few textbooks acknowledge that not all IRAC structures require a rule support section.[194] However, in “most instances,” a rule support section is “necessary” and should be omitted “only when the rule standing alone is absolutely clear.”[195]

To determine whether to include this section, a legal writer should ask three questions.[196] First, a legal writer should determine whether the rule is “difficult to understand.”[197] If so, the rule support section can help a reader comprehend the meaning of a rule by providing examples of how a court has previously applied the rule.[198]

The second question is whether the rule “insufficiently align[s]” with the client’s fact pattern.[199] If so, rule support cases “paired with analogies [can] fill [a] gap between [the] rule of general applicability” and the new fact pattern, “bring[ing] the law and [the] facts into alignment.”[200]

Finally, a writer should determine if a rule does not “align” with the client’s facts.[201] In that case, the legal writer will want to clarify why there is a lack of alignment by making a distinction,[202] which can “show that a gap exists between the law and [the] facts” and therefore the writer “cannot apply the law to [the] facts and draw a conclusion.”[203]

Selection. The textbooks that address how to select the most effective rule support cases to use in a writer’s IRAC paradigm agree on a set of guidelines for choosing which cases to include. The textbooks suggest that a writer include cases that are factually and legally analogous to the client’s fact pattern as well as cases that are distinguishable.[204] As a secondary consideration, the textbooks also suggest including cases from the governing jurisdiction that are from a higher court, more recently decided, and published, as opposed to unpublished.[205]

In addition, Brown in The Mindful Legal Writer: Mastering Predictive and Persuasive Writing suggests that a writer should select cases that “apply the rule in the most straightforward way; that give especially interesting or vivid illustrative facts to bring the rule to life; or that you personally understand the best and, therefore, can describe the most effectively.”[206] In addition, given professor-set and court-mandated word- and page-count limits, legal writers must “strike a balance of illustrating the applicable rule thoroughly yet succinctly so the audience readily understands the law without being overwhelmed or inadvertently confused.”[207]

Number of Cases. The first-year legal writing textbooks that address the proper number of rule support cases to include in the rule support section of one IRAC paradigm agree that it depends on the circumstances. At one end of the spectrum, if two potential rule support cases say the exact same thing, the legal writer should select only one case to use as the rule support case to make that point.[208] In addition, if a writer finds only one or two potential rule support cases, the writer will, “by necessity,” want to include those cases.[209]

However, if there are multiple potential rule support cases available, a writer will have to be “selective”—a reader does not have the “patience” to read about “5, 10, or 20 cases,” and the writer does not have the space to discuss all those cases.[210] Therefore, when deciding which and how many rule support cases to include, a writer should consider the complexity of the issue, the number of relevant rule support cases that are available, and the page limit or word-count limit.[211]

In general, a writer should include “several representative cases to illustrate” the rule, which will increase a reader’s “depth of understanding.”[212] To be more specific, a writer should include between two to four separate rule support cases.[213]

Order of Cases. Only a few textbooks provide writers with advice for the order to present rule support cases in. Those that do note that a writer should begin the rule support section with the cases that are most similar to the client’s case.[214] The writer should then include “any cases that are unlike [the] client’s facts” if “those cases add something relevant” to the analysis of the client’s issue.[215]

2. Writing Advice

The first-year legal writing textbooks provide relatively consistent advice regarding the proper length for each rule support case. Multiple textbooks also provide additional tips for how to write the rule support section.

Length. The textbooks that address the issue uniformly agree that the length of each rule support case varies greatly.[216] A rule support case may be one sentence long, it may require three pages of text, or it may be “somewhere in between.”[217] A writer should “vary the depth” of his or her explanation to “suit the amount of skepticism [] expect[ed] from the reader.”[218] When trying to “strike an effective balance,” a legal writer should focus on the “dual goals of clarity and concision.”[219]

Among other factors, the length of the rule support case depends on the complexity of the relevant issue and the importance of the case in the writer’s legal analysis.[220] A case with complex facts, legal issues, or both requires a “more extensive discussion than a less complex case.”[221] Also, a case that is “central” to a writer’s analysis should be presented in more detail than a case “used only for a collateral point.”[222]

The textbooks advise a legal writer to avoid “explor[ing] an issue in more depth than a reader needs” and suggest that the writer only include “what is relevant to the reader’s understanding of the issue or issues.”[223] However, new legal writers should “err on the side of making a more complete analysis” if they are unsure how much information to include.[224]

Additional Writing Tips. Many legal writing textbooks provide a plethora of detailed additional tips for how exactly to write the rule support section and the rule support cases in that section. There is not sufficient room in this Article to discuss all the helpful advice, but here are some useful and representative examples about how to write about the fact portion of a rule support case:

-

A writer should include all the legally-relevant facts and provide specific, concrete details.[225]

-

A writer should include a few generalized background or storytelling facts.[226]

-

A writer should write the facts in past tense.[227]

-

A writer should write the facts in chronological order.[228]

Multiple textbooks provide advice about writing the holding portion of a rule support case, including:

-

A writer should simply state, “The court held that . . .”[229]

-

A writer should be precise in his or her description of the court’s holding, especially when the court does not decide the case on its merits.[230]

-

A writer should generally not focus on the procedural outcome unless it is specifically relevant to the client’s situation or it is needed to precisely explain that the appellate court affirmed or reversed the lower court’s decision.[231]

The textbooks also suggest the following guidance for writing about the reasoning portion of a rule support case:

-

A writer should use the phrase “The court evaluated[,] determined[,] reasoned[,] emphasized[, or] explained” to introduce the court’s reasoning.[232]

-

A writer can include “several” sentences in the reasoning section and should connect the reasoning to the relevant rule.[233]

Finally, multiple textbooks provide general advice for writing the rule support section, including:

-

A writer should start the first rule support case in the rule support section with a transition like “For example, in [case name], . . .” or “For instance, in [case name], . . . .”[234]

-

Between rule support cases, a writer should use transitions like “Similarly/In addition/Additionally/Likewise/Further, in [case name], . . .” for similar cases or “In contrast/Conversely, in [case name], . . .” for contrasting cases.[235]

-

A writer should not use proper nouns to describe the case parties or any other relevant actors.[236] Instead, a writer should use general terms to describe the key players’ role in the rule support case, such as “employer,” “employee,” “landowner,” “tenant,” “buyer,” and “seller.”[237]

-

A writer should not mention anything about his or her client in the rule support section.[238]

3. Explanatory Parentheticals

The legal writing textbooks that discuss the issue uniformly agree that explanatory parentheticals are a useful tool to include in the rule support section.[239] In particular, for less important or duplicative rule support cases, explanatory parentheticals are a great way to efficiently include additional information from one or more rule support cases without writing an entire rule support paragraph for each one.[240] These explanatory parentheticals include the same information as a rule support paragraph—the facts, holding, and sometimes reasoning of the rule support case—but in significantly less space.[241]

In fact, in Legal Writing and Analysis, Murray and DeSanctis advocate that legal writers should use an “explanatory synthesis” structure as a default rule support section organizational scheme, instead of including multiple rule support paragraphs.[242] For this approach, the structure starts with a “[p]roposition about how the law works” followed by a string of case cites, each with its own explanatory parenthetical showing how that case “illustrates the proposition about how the law works.”[243] Murray and DeSanctis advocate that this approach is preferable because it allows a writer to include more rule support case examples in less space.[244]

4. Sensitivity to Context

Many first-year legal writing textbooks specifically address how a writer should treat rule support cases in a variety of objective contexts, including email memoranda,[245] formal office memoranda,[246] “short” memoranda,[247] oral reports to a supervisor,[248] client letters,[249] formal opinion letters,[250] and client emails.[251] Numerous textbooks use the formal interoffice memorandum as a default context for introducing and discussing the rule support section.[252] In addition, a few textbooks address how judges also often include rule support cases in their judicial opinions.[253]

Regarding persuasive drafting, some textbooks discuss the rule support section or rule support cases in the context of persuasive briefs in general, not in the context of a specific type of persuasive document, or provide guidance about persuasive writing in general.[254] In addition, some textbooks address the rule support section and rule support cases in the specific persuasive context of letters to opposing counsel;[255] trial-level motions,[256] including motions to dismiss,[257] discovery motions,[258] motions for summary judgment,[259] and posttrial motions;[260] opposition briefs;[261] appellate briefs;[262] and oral argument.[263]

IV. Pedagogical Implications

This Article describes the lack of uniformity across the fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks regarding how the textbooks address some fundamental questions about the rule support section. This diversity of approaches demonstrates the richness of our field and should be celebrated. These variations reflect the different but thoughtful and well-reasoned philosophies, pedagogical choices, and preferences of legal writing professors.[264]

Although these valuable differences are a positive, the variance raises the issues of how to reduce potential student confusion within the legal writing classroom and how to address the issue outside the legal writing classroom. After all, this diversity of approaches to the rule support section is not just a legal writing issue but also impacts doctrinal and clinical faculty. Moreover, given the importance of the rule support section, it raises the question of whether some legal writing textbooks should consider fleshing out their rule support instruction to address additional aspects of the rule support section that they may not currently address.

A. Reducing Student Confusion

The lack of uniformity implicates the issue of how to prevent confusion for law students, especially first-year students, when they are confronted with different terminology and different conceptualizations of the rule support section in their different courses, clinics, externships, and internships. To head off potential student confusion in these various situations, a legal writing professor should consider a textbook’s approach to the rule support section when selecting a textbook and should teach students about the variety of rule support approaches and terminology as early as possible.

1. The Danger of Inconsistent Approaches and Terminology

The range of different approaches to and terms used to describe the rule support section creates potential confusion for first-year law students, who lack a common conceptualization and language to discuss the rule support section of the IRAC paradigm.[265] Overwhelmed by the complexities of learning legal analysis and substantive legal content for the first time, first-year law students are often thrown off by anything that feels different or inconsistent between their various courses, their law school activities, or their legal internship or externship experiences. Although this lack of consistency may not be an issue for practicing lawyers and judges, it is a significant challenge for law students, especially in their first year of law school when they are still learning the process of legal synthesis and of translating legal analysis into the IRAC paradigm.

This issue may arise almost immediately in the legal writing classroom if a professor is using a legal writing textbook that employs different rule support terminology or a different approach to the rule support section than that professor teaches. The students may be confused that what their professor is teaching them is not consistent with the information that the students are learning in their textbook readings before class.

Alternatively, if a professor is using a textbook with a consistent approach to the rule support section, this issue may not arise right away in the legal writing classroom because the professor is able to teach his or her own variation of the rule support section. However, students are not just exposed to these questions within the legal writing classroom. Students often discuss the IRAC structure and its components, including the rule support section, in their doctrinal classrooms, in their seminars, in their clinics, in their summer job interviews, in their externships, and in their internships.[266]

If a student is first introduced to a different approach to the rule support section in one of these contexts outside the legal writing classroom, the lack of uniformity may confuse the student. The student may question the validity of part or all of what the student learned in his or her legal writing classroom. The student may feel less confident in his or her legal analysis skills in that classroom, clinic, interview, externship, or internship.

2. Textbook Selection

To prevent confusion in the legal writing classroom caused by a potential conflict between the lessons in the textbook and the lessons in the classroom, a professor should consider selecting a legal writing textbook based on its approach to rule support cases. When making this decision, a professor can take a variety of approaches. As one option, the professor may select a textbook that uses the professor’s preferred terminology for the rule support section. If a professor prefers the term “rule explanation,” there are a plethora of textbooks that primarily or only use that terminology.[267] However, if a professor prefers the term “analogous case,” “case illustration,” “explanation section,” “precedent,” “rule illustration,” or “rule proof,” there is only one textbook that primarily or exclusively uses each of those terms.[268] Therefore, that professor would be more limited in his or her textbook choices if the textbook’s nomenclature is a dispositive issue for that professor. The professor will have to determine if the textbook’s terminology should be the most important factor.

Second, a professor may choose to select a textbook based on that textbook’s overall approach to the rule support section. If the professor defines the section narrowly, he or she may want to choose a textbook with a narrow conceptualization of this section.[269] However, if the professor sees the rule support section as a broader concept that encompasses part or all of the rule section or maybe even the issue, he or she may choose a textbook that aligns with this approach.[270]

Third, a professor may opt for a legal writing textbook that favors a particular approach to one aspect of the rule support section. For instance, if a professor prefers to use explanatory parentheticals as the main organizational structure in the rule support section, that professor may want to choose a textbook that takes that exact approach.[271]

Fourth, a professor may select a legal writing textbook based on that textbook’s focus on the rule support section. If the rule support section is important to the professor, he or she may choose one of the textbooks that spends a significant amount of time addressing the rule support section and its many facets.[272] However, if the rule support section is not as important to the professor, he or she may pick a textbook with less focus on this part of the IRAC paradigm.[273] Regardless of which one or more of these factors a professor chooses to prioritize when selecting a legal writing textbook, the professor should consider making a conscious decision regarding which textbook best fits that professor’s rule support section approach.

3. Getting Ahead of Confusion

To avoid potential confusion between what students learn in their legal writing classroom and what they encounter in their other courses, clinics, internships, or externships, legal writing professors should teach students about the different potential names for and conceptualizations of the rule support section as soon as possible. Awareness is the first step to preventing student confusion. Therefore, it is essential that professors present the possibility of different approaches to rule support cases, as well as other substantive and stylistic differences, to their students. Once students are aware of the different approaches to naming and conceptualizing rule support cases, they will be able to comfortably confront those differences in their other classes, their clinics, their externships, and their summer jobs.

Legal writing professors should introduce the diversity of approaches to the rule support section, including the terminology for and conceptualization of this section, early in the first semester. Professors probably should not present this more nuanced subject when they first introduce the IRAC paradigm to their students. However, as the students start to feel comfortable with the rule support section, legal writing professors should, at a minimum, consider flagging the different terminology used for the rule support section. This approach could be as simple as including a PowerPoint slide in that lesson’s deck that lists the various ways to name the rule support section. For instance:

Legal writing professors often include a similar PowerPoint slide to demonstrate to students the different possible acronyms for the IRAC paradigm.[274]

Multiple textbooks flag the different terminology used for the rule support section, letting their reader know that the reader’s individual professors may use different terminology than the textbook author or authors employed.[275] Legal writing professors should also raise this issue in their classrooms.

Although it is a more difficult task, it is also worth noting the differences in approaches to the more substantive aspects of the rule support section. Legal writing professors should acknowledge that other professors as well as practitioners and judges may take a different approach to how to define the rule support section, what the purpose of the section is, and what to include in the section. Again, this lesson does not have to take a large chunk of classroom time.

It is a valuable lesson for law students that not all professors and practitioners take the same approach to many questions that arise in the practice of law. Students need to learn to mold their style and approach to the style and approach of their work supervisors until they are experienced and senior enough to form and institute their own preferences.

By raising the different terminology for and approaches to the rule support section, a professor can prevent future student confusion when the student invariably comes across a professor, lawyer, or judge who takes a different approach to the rule support section, whether that approach is only slightly different or more fundamentally different. If a student knows to expect this variation, the student will not be thrown off by these individual preferences.

B. Outside the Classroom

In addition, the terminology used to describe the rule support section, the basic conceptualization of this section, and the other areas of divergence are topics to discuss within the legal writing community. Although this Article provides a comprehensive empirical analysis of how the fifteen most popular first-year legal writing textbooks address the rule support section, it is just the start of this discussion. As a legal academy, we should attempt to determine if the wide variance between approaches to the rule support section is indicative of a wider disagreement among legal writing professors regarding this section.

Also, this diversity of ways to define and name the rule support section suggests that the rule support section may involve more complex skills than we originally thought. We may need to pay more attention to the rule support portion of the IRAC paradigm, digging into this section in our scholarly discussions as well as in our classrooms.

In addition, we should work to refine our own understanding of our individual approaches, which will help us confirm if we are taking the best approach and allow us to teach the other approaches to our students. We should also consider the best way to prevent student confusion while maintaining our ability to teach the rule support section in the way that we each prefer.

The diversity of approaches to the rule support section is not just a legal writing issue. It is important to talk to our law school colleagues about how to address the potential student confusion that is created by the lack of uniformity. The goal of that dialogue is not to force doctrinal or clinical professors to change their approaches but to acknowledge those differences and to figure out how to warn students about the divergent approaches to avoid confusion. Again, this process will allow each of us to also refine our own understanding of the rule support section and to determine how fundamental our differences are.

C. Approach to Next Textbook Edition