Hollywood writers have a secret. They know how to tell a compelling story—so compelling that the top-grossing motion pictures rake in millions, and sometimes even billions, of dollars.[1] How do they do it? They use a simple formula involving three acts that propel the story forward, three “plot points” that focus on the protagonist, and two “pinch points” that focus on the adversary. In fact, people have been telling stories this way for thousands of years, dating back to the first theatrical works.[2]

Legal scholars have written extensively about lawyers as storytellers and about the importance of telling clients’ stories in a compelling manner.[3] It hardly needs reiterating that “storytelling lies at the heart of what lawyers do.”[4] And structure matters. Lawyers need to think about the way their stories unfold. Their ability to communicate facts clearly to judges and juries, and their ability to persuade them, hinges on it.[5] So why not tell stories in the way people are accustomed to hearing them? Why not use the screenwriter’s method?

This Article argues that lawyers should build their stories in the same way Hollywood writers do, and that doing so will make for better, more understandable, more memorable, more persuasive stories. It deconstructs the storytelling formula used by screenwriters[6] and translates it into an IRAC-like acronym, SCOR. Attorneys who use SCOR will not have to design the architecture[7] of their clients’ stories anew each time they sit down to write. SCOR will do it for them. Using SCOR will therefore make the attorney’s job as a writer easier and quicker—and it will result in more compelling, convincing stories and, ultimately, better client outcomes. It will make the storytelling lawyers do, whether writing a client’s story in a brief or arguing it in an opening or closing statement, easier and more effective. Of course, there is no one, precise formula that will work for all attorneys or all lawsuits, but SCOR can be a useful tool, or at least a useful starting point, in a wide variety of situations.

Part I of this Article gives a brief overview of narrative theory, situating the Article’s own contribution in a branch of that theory concerned with story structure. Part II reveals the screenwriter’s secret for telling compelling stories, identifying and defining the nine dramatic beats, or “story milestones” that appear in a typical movie. Part III analyzes a brief filed in the landmark case of Miranda v. Arizona,[8] showing how the attorneys who wrote it used a SCOR-like story structure. This analysis shows that SCOR comes naturally for writers and that lawyers, like screenwriters, can use SCOR to tell powerful stories. Overall, the Article attempts to guide and inspire attorneys who want to improve their storytelling capabilities.

I. A Brief Overview of Narrative Theory

A brief overview the legal scholarship on narrative theory[9] will situate this Article within an existing body of work.

A. Debates Over Jargon: “Story” Versus “Narrative”

Legal scholars have wrestled with, and sometimes argued about, the meaning of words such as “story” and “narrative.”[10] And they have debated which word is best for the legal academy. The word story is more casual, conjuring up an “everyday concept,”[11] like an “entertaining work[] of fiction.”[12] It is unpretentious and accessible and, in this sense, comports with the prevailing stylistic preference, in legal writing, for plain English. Definitionally speaking, stories “structure . . . information,” putting it into a format that will engage an audience.[13] Stories involve “characters, their goals, and their struggles to achieve their goals.”[14] Stories present “a set of logically and chronologically related events caused or experienced by characters.”[15] But there is a pejorative view of stories and, consequently, a downside for legal scholars attracted to the term: the word “story” can “connot[e] things childish, unserious, or even deceptive.”[16]

The word “narrative” is broader than story. It can apply not only to a statement of the case, where a lawyer is actually telling a story, but to other types of writing lawyers do, like analogizing the facts of precedential cases to the facts of the client’s case[17] or writing a complaint.[18] Narrative is also a less-casual word than story. It is “more abstract and academic sounding. It feels weightier, more serious, more prestigious . . . .”[19] Definitions of narrative differ. Some are quite complex, involving words that themselves have elaborate definitions, such as “theme,” “discourse,” and “genre.”[20] Others are simpler: according to the dictionary, a narrative is “a spoken or written account of connected events,” something “distinct from dialogue.”[21] Some definitions equate narrative and story[22]—a confusing approach, at least for purposes of this discussion, but one that probably reflects the everyday understanding of these words.

Both words, story and narrative—as well as other words not discussed here—have advantages and disadvantages in terms of their use in legal scholarship. This Article relies mostly on the word story and its derivatives because the Article’s focus is on briefs (in particular, preliminary statements and statements of the case) and, to a lesser extent, opening and closing arguments. These are places where lawyers tend to engage in something that looks in a commonsensical and uncontroversial way very much like “storytelling” as we usually understand that term. The word story thus seems appropriate content-wise and its simplicity seems appropriate in terms of readability.[23] Overall, the Article treats story as a particular type of narrative; it uses the phrase “narrative theory” to refer to the study of narratives, including the study of stories.

B. Major Themes in the Legal Scholarship

Legal scholars who write about narrative theory have approached the topic from a number of different perspectives.[24] Enumerating and classifying those perspectives, though, is difficult. There are certainly identifiable themes in the scholarship, but they do not necessarily express perfectly discrete viewpoints. The themes’ boundaries are murky and overlapping. One article, or one era, might evidence several perspectives at once.[25] This section’s summary of the scholarship is consequently imperfect and, as the Article’s primary goal is not to serve as a detailed chronicle of narrative theories, more intuitive than methodical.

All that said, one of the first perspectives on narrative theory was an outsider perspective: legal realists and critical race and feminist scholars used stories to “celebrate diversity” and “challenge and disrupt [the] . . . dominant group’s discourse about the law.”[26] Their scholarship overlaps with another, jurisprudential, perspective, which “explores the narrative roots of human decision-making.”[27] The jurisprudential perspective views “narrative as a preconstruction—an often unacknowledged frame that determines which legal outcomes we will embrace, at least initially.”[28] In this branch of narrative theory, the focus is on decisions, not on rationales or explanations for decisions.[29]

It is another branch of narrative theory—one that might be called “the discourse perspective”[30]—that focuses on explanations. Scholars writing from this perspective analyze, among other things, what lawyers and judges say, and how they reason, in briefs and judicial opinions.[31] They are interested in how we demonstrate adherence to the rule of law, or at least give the impression of adherence to the rule of law, in legal writing.[32] Some discourse scholars focus on prose style: writing that comports in a stylistic way with the legal community’s professional standards. Legal-writing textbooks for first-year law students are written almost exclusively from this perspective.[33]

Another branch of narrative theory focuses on persuasion.[34] This branch explores narrative as a “lawyering tool.”[35] Its proponents often focus expressly on legal-writing instruction, that is, on how storytelling can make law students into effective lawyers.[36] They want to leverage the dramas that naturally play out in lawsuits.[37] They are concerned, for instance, with infusing pathos into briefs. They contend that “a brief that relies purely on a logos-based argument will be lifeless.”[38] But the persuasion perspective has a critical branch, as well, which is concerned with the potential for abuse of narratives in a legal system where cases are supposedly won and lost on their merits (and not, say, on courtroom theatrics). After all, a good storyteller can persuade someone to believe what he is saying even when he is bending the truth or telling outright lies.[39] These scholars question whether too much emphasis on persuasion in the form of narrative, rather than logic, is appropriate.[40] Put simply, “the persuasiveness of a story does not turn on its truth . . . [and i]n the legal context, truth matters. If stories can persuade whether they’re true or not, that’s not good.”[41] In other words, there may be some stories that, for lawyers, just go too far.

Weaving its way through all of these approaches is perhaps another perspective, one that emanates from the cognitive sciences. This branch of narrative theory explores how stories influence human beings at a subconscious level.[42] Scholars writing in the area have discussed stories as “‘a cognitive template against which new inputs can be matched and in terms of which they can be comprehended.’”[43] They have explored the concept of “stock stories,” those tales that are the “ubiquitous” and “commonly accepted cultural scripts” that groups use to define themselves.[44] These stories can be fairy tales like Cinderella, or modern tropes like “the deadbeat dad.”[45] They are immediately recognizable.[46] They help us understand information more quickly—and they bias us, as well.

A final perspective on narrative theory, which could be called the structural perspective, is this Article’s conceptual home. Structural theorists write about story architecture as distinct from story content.[47] They often take a pragmatic or pedagogical approach, as do some of the scholars discussed above. Their position is that “[a] large part of telling an effective story is the order in which the writer presents information.”[48] In their view, good stories need more than just “linear continuity. Simple succession is meaningless. It creates neither a story nor a lawsuit.”[49] Scholars who approach narrative theory from a structural perspective believe that good story structure can increase a client’s chance of winning: Good story structure helps triers-of-fact understand and remember information.[50] And the story that seems most coherent (that is, the story that seems to flow most logically[51]) “will also be the story that seems most probable.”[52] In short, good stories produce “more predictable judgments.”[53]

The scholars above, varied as their perspectives might be, all agree that stories matter, that their importance “in legal discourse is not debatable.”[54] For lawyers in common-law countries like the United States, storytelling is a necessity because stories are “embedded in the rule’s structure, and the rule can be satisfied only by telling a story.”[55] Arguably, “no one can . . . practice law without telling stories.”[56] This is especially true for litigators: the client will win only if the attorney persuades a judge or jury; the ability to persuade a judge or jury hinges on the quality of the attorney’s brief or oral argument; the quality of the brief or oral argument hinges on the quality of the facts section; and the quality of the facts section hinges on the quality of the story it embodies.[57] In fact, one study shows that judges are more persuaded by briefs that rely on stories, in addition to logic, rather than solely on the latter.[58] Ultimately, judges respond to stories, just like any other person does.[59] Thus, “the more useful question is not whether to tell a story, but how to tell it.”[60]

C. This Article’s Contribution

This Article takes a structural approach to narrative theory. It is concerned with the architecture of stories, not their content. It focuses, in particular, on coherence—the relationship between the parts of a story.[61] It drills down deeper into the familiar but also fundamental concept of the three-act story, explaining how screenwriters punctuate those acts with story milestones that could apply equally well to fictional tales told in motion pictures as to real, human dramas told in the context of lawsuits. Ultimately, it takes the position that lawyers who use standard screenwriting methods to tell their clients’ stories will be better advocates.

The Article has two goals. The first is to make it easier for judges and jurors to understand sometimes quite complicated facts where the stakes of winning and losing can be very high and where people’s wellbeing, and sometimes even life and liberty, might be on the line. Judges read hundreds of briefs a year.[62] They are, one might say, “major consumer[s] of legal writing,”[63] and, as such, they “provide an invaluable source of information about the . . . quality of written . . . work . . . and how good and bad brief-writing directly affects the judicial process.”[64] Unfortunately, based on their regular remonstrations of attorneys for poor writing, they do not seem pleased; apparently, “bad briefing is all too common in federal and state courts.”[65]

Part of the problem is poor organization,[66] and this Article addresses that issue. Triers-of-fact can understand an organized story better than a chaotic one. And they can understand a story told in a familiar style better than one (even an organized one) told in an unfamiliar style. That is the very reason lawyers use IRAC or some derivative to organize arguments; it is not necessarily the best or only way to present a logical argument, but it is the agreed-upon way and the way a lawyer’s audience expects it to be done. A lawyer could make a good, logical argument in some way that bore no resemblance to IRAC, but it would probably confuse and annoy her reader. The same is true for client stories: stories that conform to the familiar architecture used in plays, books, and movies will resonate better with judges and juries.

The argument here is similar to that advanced by proponents of stock stories. Stock stories are persuasive, the argument goes, because they “fit with other stories the listener has heard.”[67] The same can be said of screenplay architecture—not in terms of content, like stock stories, but in terms of structure. That structure, divorced from content, functions like a stock story: it “reduce[s] complexity” and “accommodate[s] the limited cognitive capabilities of human beings”[68] to comprehend new information. In short, the architecture discussed in this Article will allow attorneys to take whatever content they might have, whether it fits nicely into a stock story or not,[69] and make it accessible to judges and juries.

It might also make reading or hearing the stories lawyers tell more pleasurable, at least on the level of language if not content.[70] The point is not that lawyers should entertain judges and juries. That is not their job. But they must engage them. And why not use language to its full effect? Why not make reading enjoyable for a judge? Why, as Gertrude Stein put it, “should a sequence of words be anything but a pleasure?”[71] Lawyers must draw their audiences in. And they can do so by telling effective stories. Good storytelling can “capture a busy judge’s attention.”[72] Stated differently (and more humorously), “[i]t is impossible to persuade a judge who is asleep.”[73]

The Article’s second goal is to make one of the hardest jobs a lawyer faces—writing an accurate, understandable, and persuasive facts section[74]—a little bit easier and quicker. It does with fact sections what IRAC does with argument sections. It gives lawyers a flexible, generally applicable template they can use each time they tackle a new case. Instead of sitting down in front of a blank page, having to invent something from scratch, they will have a prefabricated schematic—SCOR—at their disposal. In the 1970s, English professor Betty Flowers identified four writing stages: Madman, Architect, Carpenter, and Judge.[75] The second, Architecture, stage is where writers arrange their thoughts into primary units. SCOR will enable lawyers to skip the Architecture stage entirely when writing a facts section (as IRAC enables them to do when writing an argument section). SCOR will also help them control the fear that many authors experience during the second stage of writing when they are staring at a blank page with no idea how to start. In addition, it addresses an area of weakness in legal-writing instruction: the rigorous attention given in law teaching to crafting an effective argument is largely absent with respect to facts sections.[76]

Writing is hard. No one is born with the ability to organize a story. First drafts do not come out perfectly structured. Some lawyers are natural storytellers, but they still need to work to get their stories right when they go down on paper. As Syd Field, “the master of the screenplay,”[77] put it, “[t]alent is God’s gift; either you’ve got it or you don’t. But writing is a personal responsibility; either you do it or you don’t.”[78] There is no substitute for hard work. The good news is that writing is “a craft that can be learned.”[79] True, it is a skill “that requires initial training, focused study, repeated practice, and conscious evolution throughout the arc of one’s legal education and career.”[80] And, true, it is an endeavor that “lawyers cannot jettison . . . because they lack innate talent, do not enjoy it, or believe they have more important tasks to perform.”[81] But good writers are made, not born. Those who struggle can learn to struggle less with methods like those this Article provides.

The bottom line is that lawyers must tell stories. They can do that job badly, or they can do it well. This Article, I hope, will be one more among many existing articles that will help them do it well. It is not about bending ethical rules. It is not about persuading judges and juries to do something they should not do.[82] It is not, additionally, about imposing a single, rigid way of doing things on everyone. It is simply one tool among many that an attorney can use both to make the job of a lawyer-storyteller easier and to make stories more accessible to judges and juries. The architecture it advocates will work for most cases most of the time.

II. THE SCREENWRITER’S SECRET TO TELLING A GOOD STORY

Legal-writing professor Bryan Garner advises lawyers to “[l]earn to see and express a story in your writing, because in effect you’re a storyteller. You’re telling the story of . . . the case, with a beginning, a middle, and an end.”[83] The last part of that advice, about the “beginning, . . . middle, and . . . end,” comes straight from the realm of creative writing: a story, at root, is a narrative with three acts.[84]

Of course, fiction-writing is different from legal writing. Novelists and screenwriters have license to invent events and situations, but “[l]awyers . . . are bound by the evidence.”[85] One of the first things a lawyer does, then, is fact-gathering, eliciting information from the client, adversary, and others and determining what the evidence actually is. That activity is akin to Flowers’ first stage of writing, the Madman stage, where a novelist “writes crazily and perhaps rather sloppily,” jotting down all of the ideas that will form the basis for her tale.[86] For novelists and lawyers alike, this is a chaotic, pre-story stage. Possibilities abound. However, both at some point must embark on the second stage of writing, the Architecture stage. At that point, the author’s role is primarily shaping the story structure.[87] So, for litigators, once discovery is over and the evidence is set, the question becomes Given the evidence, how do I build a story that will best meet my client’s goals?[88] The client’s story will always be “rich with details,” just like the ideas the novelist produces during the Madman stage, and lawyer and novelist must both avoid getting bogged down in those details.[89] Using a traditional three-act story structure helps novelists avoid the bog and it can help lawyers avoid it, too.

A. Basic Story Architecture: “A Tragedy in Three Acts”

Almost everyone has heard the phrase “a tragedy in three acts.” That is because plays have been written with three acts for thousands of years. Over time, the three acts have become “the basis of Western storytelling.”[90] They are used today, almost without fail, in popular novels and movies. According to screenwriter Freddie Gaffney, “[t]he three-act structure is an established form in mainstream screenwriting.”[91] Different people may give different names to the three acts.[92] Some people even divide stories so they appear to have more than three acts; many narrative theorists have, for instance, recognized a five-part story structure: (1) an initial steady state; (2) a period of trouble; (3) a period involving efforts to rectify the trouble; (4) a restoration of the steady state (or a transformation into a new steady state); and (5) a coda, like a moral of the story, for closure.[93] Arguably, though, a “story must, by definition, . . . adhere to a three-act underpinning.”[94] In the words of screenwriter David Howard, “You can call them other things or count their parts in a variety of ways, but in the end it still comes down to the fact that each of these three things must be there and functioning in order for a story to work.”[95]

Typically, Act I, the beginning of the story, is called the “Setup.”[96] The Setup is where the audience learns about the status quo, or what the protagonist’s life is normally like.[97] Act II, the middle of the story, is called the “Confrontation.”[98] In Act II, the status quo is over and the story begins in earnest. This is the meat of the story. The protagonist has a goal, but must overcome a series of obstacles to accomplish that goal.[99] Act III, the end of the story, is called the “Resolution.”[100] In it, the tension, which has been rising throughout the rest of the story, begins to fall and the audience is given some closure and some idea what the main character’s “new normal” is like.[101] During the Resolution, all story lines are resolved, and no question is left unanswered.[102] Figure 1 illustrates this fundamental and commonplace story structure.

Arguably, the three-act structure is universal and all stories contain these attributes of setup, confrontation, and resolution.[103] The structure seems to be embedded in the human psyche, a “natural way[] of understanding” life.[104] Potential sources or affirmations of the three acts seem to be everywhere, like birth, life, and death[105] and morning, afternoon, and evening.[106] Some posit that the three-act structure is an inherent feature of the human mind, a sort of pre-linguistic, psychological imperative.[107] Others posit that it is inherent in language.[108] The structure resonates, they say, because the human condition is the same no matter the time or place.[109]

Gaffney tells aspiring screenwriters to master the three-act structure even if they do not plan to use it: “it is essential that you are aware of how it works and why it works . . . even if you don’t want to be restricted by its constraints.”[110] The same advice could be given to lawyers. The rules of legal writing, and the rules of story architecture, can always be broken. This is especially true for the most gifted writers and advocates. But knowing the rules, recognizing when you are breaking them, and having a good reason for doing so are the hallmarks of excellence, whether in screenwriting or legal writing.

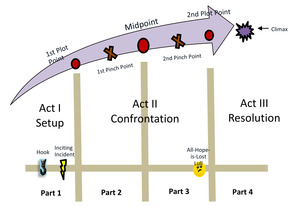

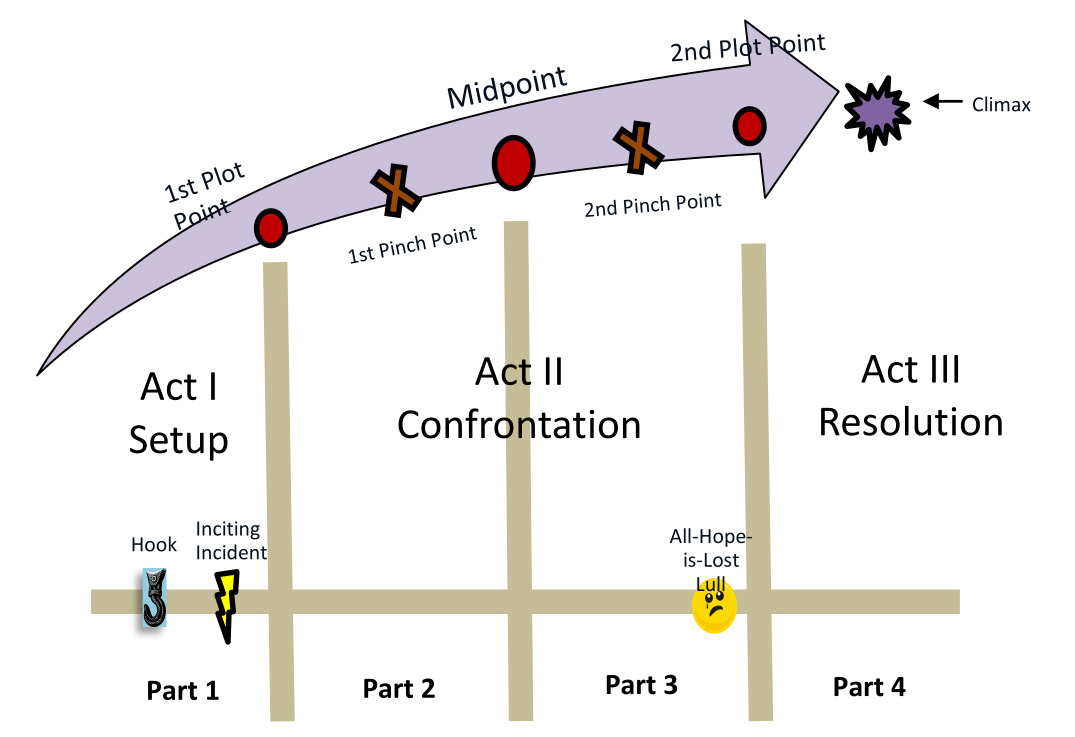

B. Advanced Story Architecture: Story Milestones

Screenwriters start with the basic, three-act architecture, just discussed, but then take it to a higher level, punctuating each act with unique milestones particular to the tale’s beginning, middle, or end. Figure 2 illustrates this advanced story architecture, showing the acts and their milestones, as well as an overarching “story arc” indicative of rising tension throughout the first and second acts and falling tension during the third. As Figure 2 shows, a standard two-hour movie can be divided into four thirty-minute parts where Act I occupies the first thirty minutes (that is, the first quarter), Act II occupies the next sixty minutes (that is, the second and third quarters), and Act III occupies the final thirty minutes (that is, the last quarter).[111] The movie still has three acts, but the acts are different lengths; content-wise, the movie has three acts, but time-wise, it has four quarters.

The following subsections discuss the concepts illustrated in Figure 2 more fully. In the spirit of IRAC, this Article introduces the acronym SCOR to make the lawyer’s job of telling the client’s story easier. SCOR stands for Setup, Confrontation, Outcome, and Resolution. It reflects a model “that has evolved out of successful screenwriting, . . . a formula that is carefully focused on moving the narrative forward . . . with specific events or incidents required to happen” at certain points in the story.[112]

1. “S” is for Setup

The first quarter of a typical movie is occupied entirely by Act I, the Setup; this is indicated in the SCOR acronym by the letter “S.” The Setup is where the author describes the protagonist’s status quo. For a lawyer, the client is the protagonist. Furthermore, assuming the client is involved in a lawsuit, some bad event—the one that gave rise to the lawsuit—has occurred. Consequently, a litigator writing Act I might want to ask herself, “What was my client’s life like before the bad event?” Often, the lawyer will want to paint a rosy picture of her client’s life in Act I. Beyond that, the lawyer needs to consider Act I’s unique milestones: the Hook, the Inciting Incident, and the First Plot Point.

The Hook is the attention grabber. It is a “visceral, sensual, emotionally resonant” scene that “makes a promise of an intense and rewarding experience ahead.”[113] It raises a story question. In other words, “[i]t’s a simple something that asks a question the reader must now yearn to answer, or it causes an itch that demands to be scratched.”[114] The Hook occurs early on in the story.[115]

The second milestone, the Inciting Incident,[116] is probably the hardest to understand. One author defines it as “[a]n event that causes the opening balance to become unglued and gets the main action rolling.”[117] Another defines it as “an abrupt change or complete reversal in a character’s ‘normal’ life that causes serious trouble and conflict.”[118] But these definitions are confusing; they seem to conflate the Inciting Incident with the First Plot Point, the final milestone at the end of Act I.[119] A better view is that the Inciting Incident and the First Plot Point are different.[120] The Inciting Incident precedes the First Plot Point and its sole purpose is to prompt the transformative event. Thus, the Inciting Incident not only happens at a different point in the story than the First Plot Point, it also has a different content and purpose. Another difference, arguably, between the Inciting Incident and the First Plot Point is that the former is something that happens to the main character, and the latter is something he does. During the Inciting Incident, someone or something forces the protagonist to make a choice. It presents the protagonist with a quest, and he can accept the quest or not. The First Plot Point is where he decides.[121] It is the point at the end of Act I where everything changes. In litigation, it is where the bad event occurs. The rosy picture the lawyer has been painting about the client’s status quo is turned upside down. In a fictional story, the First Plot Point can be bad or good, blatant or subtle,[122] but it is, at essence, transformative: it is an event that fundamentally changes the status quo, presents some sort of conflict, produces tension in the audience, and gives the protagonist a goal.[123] It is where the story really begins.[124] Act I itself is not a story; it is simply a setup for the Confrontation. The story begins in earnest at the First Plot Point.[125]

The movie The Wizard of Oz is by some accounts the most significant Hollywood film ever made.[126] It is also a classic quest story: Dorothy, having become stranded in a strange land, is trying desperately to find her way back home. In order to fulfill her quest, she has to overcome numerous hurdles. If the movie is true to the SCOR format, the Setup, or Act I, should be about Dorothy’s status quo, her normal life before the transformative event occurs. To spice things up, though, we expect a Hook, an Inciting Incident, and a dramatic shift represented by the First Plot Point. Does the movie deliver? Absolutely.

Act I introduces Dorothy, Auntie Em, Uncle Henry, and the three farmhands who will eventually become the Scarecrow, the Tinman, and the Cowardly Lion. It shows what life in Kansas is like: there is hard work, but also camaraderie. Dorothy, like any young girl, has her complaints, but, all in all, she seems to have a fairly idyllic life. And then we get the Hook: Dorothy’s neighbor, Miss Gulch, wants to euthanize Dorothy’s beloved dog, Toto. She arrives at the farm, produces an official order allowing her to take Toto to the sheriff, forces Toto into a basket, and rides off on her bicycle with the dog in tow. Something sinister has entered the picture and the audience’s attention has been grabbed. Toto manages to escape and return home to Dorothy. This produces the Inciting Incident, a series of scenes starting with Dorothy and Toto running away from home. The pair is only gone a short time, but, importantly, they are off the farm while the cyclone is approaching and the others are getting themselves safely stowed in the storm cellar. If it were not for the running-away scene, Dorothy would have been down in the storm cellar with everyone else when the cyclone hit.

As events would have it, though, Dorothy cannot get into the storm cellar. So, she goes into the house where she is hit on the head by flying debris and rendered unconscious.[127] The house is swept away, with Dorothy and Toto inside, to the magical Land of Oz. This brings on the First Plot Point, that event near the end of Act I that changes everything, the point where the story really begins. SCOR puts the First Plot Point at the end of the first quarter, and this movie is not far off. At just about the right time, several things happen that make clear that Dorothy has been set on a quest: she opens the door to the farmhouse and the black-and-white of Kansas gives way to the Technicolor of Oz, she learns that she has inadvertently killed the Wicked Witch of the East, magical ruby slippers suddenly appear on her feet, she expresses her desire to get back to Kansas, and Glinda the Good Witch tells her that the only way to get back to Kansas is to ask for help from the Wizard of Oz in the Emerald City. That is as clear and as well-timed a First Plot Point as one could hope for. The Setup is over and it is time for the Confrontation. The story has begun!

2. “C” is for Confrontation

The second and third quarters of a typical movie consist of Act II, the Confrontation; this is indicated in the SCOR acronym by the letter “C.” The Confrontation is the meat of the story: the status quo depicted in Act I is over and the protagonist is reacting to the new situation engendered by the transformative event that occurred at the First Plot Point.[128] He has a goal, but he must overcome a series of obstacles in order to accomplish it.[129] His journey is not plotted by a straight line. There are curves in the road and he is busy trying to navigate those curves—sometimes unsuccessfully.[130] However, with each attempt, he is getting stronger. He is acquiring the skills, tools, power, or knowledge he needs to reach his goal. The problem is that the adversary is also getting stronger.[131] Consequently, the five milestones that punctuate Act II focus not only on the protagonist, but on the antagonist as well.

Lawsuits are fertile ground for Confrontation because they necessarily involve an adversarial contest where each side has some strengths and some weaknesses.[132] These strengths and weaknesses can relate to the facts of the case, the governing legal rules, or both. Therefore, a litigator writing Act II might want to ask herself, “What are the outcome-determinative facts?” and “What are the legal principles the client must establish or disprove to win?” These pivotal facts and rules may well become the hurdles the protagonist must surmount in Act II.[133]

A lawyer writing Act II must also ask herself, “Who or what is the antagonist?” Often, the opposing party will be the antagonist, especially for sympathetic clients. In some lawsuits, though, especially those with less-sympathetic clients, the antagonist might be more subtle and may be something unrelated to the opposing party, like mental-health problems, addiction, childhood trauma, or poverty. The SCOR formula does not depend on an archetypal hero-villain situation. All it requires is a client with goals and obstacles to achieving those goals. The client might be flawed and the opposing party might not be the antagonistic force preventing the client from succeeding.[134]

Act II consists of five milestones: the First Pinch Point, the Midpoint, the Second Pinch Point, the All-Hope-is-Lost Lull, and the Second Plot Point. These milestones, like all of the milestones discussed in this Article, give stories added structure beyond the three-act layout and keep audience members engaged and in a state of tension as they await the story’s ultimate conclusion.

The first milestone in Act II, called the “First Pinch Point,” features the antagonist. Linguistically, “Pinch Point” may sound a lot like “Plot Point,” but do not confuse the two. Plot Points always feature the protagonist.[135] Pinch Points always feature the antagonist.[136] In fact, the First Pinch Point is the audience’s first opportunity to clearly view the adversary.[137] The adversary can be obvious, like a fire-breathing dragon, or subtle, like a drug addiction. Regardless, the First Pinch Point makes clear what the protagonist is up against and how formidable the adversary is.

Act II’s next milestone, the Midpoint, is essentially a Plot Point; it is called the “Midpoint” simply because it happens to fall squarely in the middle of the story. Like a Plot Point, the Midpoint features the protagonist. The Midpoint is where the protagonist gets something—some information or skill or power—that makes it appear he will finally be able to reach his goal.[138] But appearances can be deceiving. The protagonist has been getting stronger, but so has the antagonist.

This brings the story to the Second Pinch Point, which, like any Pinch Point, features the adversary. This is the audience’s second clear view of the antagonist and it shows that the opponent is still a worthy foe, despite the protagonist’s increasing strength.[139]

The Second Pinch Point is closely related to the milestone that follows it, the colorfully named All-Hope-is-Lost Lull.[140] This is where the audience is poised for a climax, expecting the protagonist to win, but experiences a letdown. The climax does not happen. The protagonist does not succeed. And the audience has its doubts he ever will succeed.[141]

The final milestone in Act II, the Second Plot Point, occurs at the end of the Act. Being a plot point, it features the protagonist. It is where the protagonist gets the final thing necessary to succeed.[142] It is usually a crisis point.[143] The audience members know, now, that the protagonist has the ability to succeed, but they do not know if he will succeed.

The Wizard of Oz provides a good illustration of Act II. If the movie follows the SCOR format, Dorothy should face numerous hurdles as she tries to succeed in her quest of returning to Kansas. Does this happen? You bet! As anyone who has seen the movie knows, Dorothy has to figure out which road leads to the Emerald City, fight off flying monkeys, acquire the Wicked Witch’s broom, and navigate many other obstacles before succeeding in her goal. And every time she successfully navigates one obstacle, an even more difficult one appears. She gets stronger with each triumph, but so does the Wicked Witch. Each side keeps upping the ante. In other words, the overall texture of Act II—as Confrontation—is exactly as the SCOR formula would have it.

Act II’s milestones also fall into place quite nicely. The First Pinch Point occurs at precisely the right time, halfway through the second quarter, when the Wicked Witch of the West throws a fireball at the Scarecrow, nearly destroying him. This is the audience’s first clear view of the antagonist’s capacity for evil. Then, the Midpoint occurs, as it should, at the halfway mark, where Dorothy slaps the Cowardly Lion in the face, standing up to what seems at this point in the story (before the Lion is exposed as a coward) like a wild and ferocious animal.[144] She shows tremendous courage, the sort of gumption that might mean she can actually defeat an opponent as strong as the Wicked Witch and, ultimately, find her way back to Kansas.[145]

The next milestone, the Second Pinch Point, again features an antagonistic force, but, this time, it is not the Wicked Witch. Instead, it is the Wizard of Oz, who is revealed as a fraud, an ordinary man masquerading as an extraordinary wizard. He can only offer one way back to Kansas: flying there in a hot-air balloon. This is where the All-Hope-is-Lost Lull occurs. As the Wizard, Dorothy, and Toto are about to depart in the hot-air balloon, Toto sees a cat, jumps out of the balloon’s basket, and runs off. Dorothy follows and the hot-air balloon leaves without her. It seems that Dorothy has finally failed in her quest, that she has exhausted every possible route for getting back home. But the next milestone, the Second Plot Point, delivers new hope, exactly as it should. This is where Glinda the Good Witch tells Dorothy that she has always had the power to get home, that the ruby slippers will take her there. It is the end of Act II where the protagonist gets the final bit of information that allows her to succeed in her quest. The viewers are now poised for a climax. They do not know whether Dorothy will succeed or fail in her attempt to reach Kansas but, either way, the movie is about to reach its emotional peak.

3. “O” is for Outcome and “R” is for Resolution

This brings the story to its last quarter, which is occupied entirely by Act III. At the beginning of Act III, the protagonist either reaches, or fails to reach, his goal.[146] This is the Outcome of the protagonist’s quest, indicated by the letter “O” in the SCOR acronym. The rest of Act III, the Resolution, is indicated by the letter “R.”

The Resolution is where the tension, which has been rising throughout the rest of the story, begins to fall and all loose ends are tied off. It is where the audience gets closure.[147] The protagonist has undergone a fundamental change and Act III shows what his new normal is like. Importantly, “no new expositional information may enter the story. . . . If something appears in the final act, it must have been foreshadowed, referenced, or already in play. This includes characters—no newcomers are allowed.”[148] This is especially apparent in the mystery genre. Fans of mysteries expect to be able to solve the mystery themselves. If the author, in solving the mystery in Act III, introduces new information, the reader feels cheated. A tacit agreement between reader and writer, that no outcome-determinative information will be delivered in Act III, has been broken.

In The Wizard of Oz, Act III is quite identifiable. It begins, of course, right after the Second Plot Point, where Glinda explains to Dorothy that she has always had the power to get home. This is where the climax occurs: Dorothy clicks her heels three times and says “There’s no place like home” and then she is back in her own bed, in her own room, in Kansas, with Auntie Em tending to her. At that moment, in a dramatic aesthetic flourish, the movie changes from Technicolor back to black-and-white. Dorothy is surrounded by all of the same characters that surrounded her in Oz—the Scarecrow, the Tinman, the Cowardly Lion, and even the Wizard—but they have all returned to their more mundane rolls as farmhands and, in the Wizard’s case, an itinerant fortuneteller. When she tells her fantastical story about Oz, her family and friends laugh in disbelief. The viewer is left to speculate whether Dorothy was just having a dream about Oz or actually visited the magical realm. Either way, Dorothy has been deeply changed by her quest. She has a new appreciation for her life in Kansas.

For legal writers, Act III is probably the most difficult act to write. The rule about avoiding “new expositional information” is easy because lawyers are already familiar with it. In a memorandum or brief, the facts section must include all material, outcome-determinative facts—all of the facts, in other words, needed in the A of IRAC. An attorney cannot spring some new fact, one that makes a difference in who wins or loses, one that has not been substantiated by citation to verifiable evidence in a facts section, in the A of IRAC. This is part of the repetition, required in memoranda and briefs, that seems so unwarranted to many beginning legal writers.

But Act III otherwise presents lawyers with more of a conundrum than the other acts do. A lawyer cannot resolve her client’s story in Act III in the same way a screenwriter can. She cannot simply write it the way she wants it to be because legal rules “dictate how . . . real-life stories should end.”[149] In fact, many narrative theorists believe that judges furnish the resolutions to legal stories.[150] At best, they say, a lawyer can only invite the desired resolution, not write a true Act III:

until the trial ends or the case settles, there is no resolution. The goal of the lawyer, then, is much like the fiction writer’s, but with a twist—to portray the characters and conflict in such a way that the resolution the lawyer seeks “fits,” and . . . the judge will naturally choose that resolution over the competing resolution offered by the opposing party. And here is a further twist—the resolution that fits a lawsuit must meet certain standards. Instead of poetic justice, judges seek actual justice.[151]

This author is not so sure. Yes, there may be times when lawyers must leave Act III for judges to write, or when they choose to do so for strategic reasons. But it is probably more often the case that lawyers can produce traditional, well-developed, screenplay-like resolutions by viewing themselves as writing one chapter in the client’s story rather than the client’s whole story. After all, a chapter can be a complete vignette—a story-within-a-story—with all three acts.

Lawyers taking this approach might write their final acts in terms of policy or slippery-slope arguments. Or they might write their final acts to raise story questions that the judge must answer. For example, in a death-penalty case, like Furman v. Georgia,[152] the story would hinge on whether the “main character live[s] or die[s].”[153] In a gay-marriage case, like Obergefell v. Hodges,[154] it would hinge on whether the main character is able to “[g]et married.”[155] In an election dispute, like Bush v. Gore,[156] it would hinge on whether the main character “[w]in[s] the election.”[157] For a criminal defendant, it would hinge on whether the main character “[r]eturn[s] home safely.”[158] These quotations were all taken verbatim from a book on screenwriting; they demonstrate that the exact same stakes at issue in motion pictures are at issue in an even more relevant and poignant way in real-life lawsuits. And they offer ideas for an Act III that can still function as Resolution even it does not serve as closure for the entire case. In short, legal writers can treat Act III in the same way that many contemporary screenwriters do: use “the final moments of act three to set up a sequel . . . usually . . . by leaving a storyline unresolved.”[159] Movies that have sequels still have final acts, and so can a story told by an attorney prior to the case’s ultimate outcome.

III. THE SCOR FORMULA IN LANDMARK SUPREME COURT BRIEFS

The last section revealed the screenwriter’s secret for telling compelling stories. It identified all of the story milestones that appear in a typical movie, and then it defined them, using an old standby, The Wizard of Oz, to illustrate and bring life to those definitions. It also presented a simple acronym, SCOR, to help attorneys use story milestones in briefs and oral arguments.

This section analyzes a landmark Supreme Court brief, filed in the well-known case of Miranda v. Arizona,[160] showing how it generally adheres to a three-act story structure and evidences most of the story milestones required by SCOR. The attorneys who wrote the brief certainly did not have SCOR in mind and probably were not versed in screenwriting methodology. Their seeming unconscious adherence to standard screenplay architecture consequently supports the idea that this architecture is fundamental to Western storytelling and may even be embedded deeply in the human psyche.

The brief provides a good exemplar for readers wishing to use the SCOR formula in their own legal writing—especially those who might be representing somewhat unsympathetic clients. And it bolsters the argument that lawyers should be more conscious of standard story architecture and use it more deliberately and strategically, at least in some cases.

A. Miranda v. Arizona, Petition for Certiorari

Miranda v. Arizona is the iconic case that prevents prosecutors from using certain inculpatory statements at trial unless the defendant was informed of her rights to counsel and against self-incrimination before making the statements.[161] The case is so famous, it has its own commonplace, the “Miranda warning.”

The defendant, Ernesto Miranda, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, was convicted of kidnapping and raping Patricia Weir. His case made its way through the Arizona court system, eventually reaching the Supreme Court of Arizona, where Miranda lost. Miranda’s attorneys then wrote a Petition for Writ of Certiorari, asking the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case. The Petition starts with a statement of facts, titled merely “Statement,” which conforms to the SCOR recipe surprisingly well.

As an initial matter, though, before delving into SCOR, it is important to note that the Statement’s authors had to make choices about who would be their protagonist and who would be their antagonist, and that these choices were intertwined with their client’s identity and their professional roles. From the prosecution’s perspective, and probably from the typical reader’s perspective, the protagonist is the victim, Weir, and the antagonist is the criminal who hurt her, Miranda. But from defense counsel’s perspective, things are different. The protagonist is Miranda; the rules of professional conduct require as much; it goes without saying that a criminal defendant’s attorney must “zealously assert[] the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system.”[162] For defense counsel, furthermore, the antagonist is not the People, the prosecution, or, obviously, the victim.[163] It is, rather, a flawed justice system. This will almost always be the situation for defense counsel in a criminal case: the antagonist will not be a person. It will be some nefarious force, like drug addiction, mental illness, poverty, or injustice.

Assessing the Statement vis-à-vis the SCOR layout, Act I, the Setup, should humanize the protagonist and show what his life was like before the bad event, and the Statement delivers. It begins by introducing Miranda in as sympathetic a light as possible, as “a 23 year old indigent.”[164] It then proceeds to the first story milestone that any Setup should have, the Hook. In fact, it wraps the Hook into that same, initial sentence, expressly acknowledging that Miranda has been charged with a terrible crime: the “kidnapping and rape of . . . Patricia Weir.”[165] Then, exactly where the end of Act I (and the First Plot Point) should be, the Statement declares that “the police took a confession from the defendant without ever advising him of his right to counsel.”[166] This is, from the perspective of defense counsel at least, the point at which Miranda’s quest for justice begins. It fundamentally changes Miranda’s status quo and gives him a goal.[167]

With that, Act II, the Confrontation, begins. SCOR dictates that the First Pinch Point feature an antagonistic force, and the Statement seems, again, to deliver. It first describes Miranda’s confession, given without the benefit of what we would call today a “Miranda warning.” Then, precisely where one would expect the pinch point, the Statement explains that this “confession . . . [was] received in evidence” at trial.[168] It is one thing to take a confession without reading someone his rights. It is another to introduce the confession at trial. This is a pinch point that could have been developed by a screenwriter. It gives the reader a clear view of the antagonist in the form of an unfair trial and a flawed system of justice.

The next story milestone in the SCOR formula is the Midpoint, where something happens that makes it more likely that the protagonist will succeed in his quest. At just the right time, the Statement delivers a block quote, set off visually from the rest of the text, that reads a lot like a Midpoint. The quote is from Miranda’s defense counsel, at trial: “We object [to introduction of the confession] because the Supreme Court of the United States says a man is entitled to an attorney at the time of his arrest.”[169] This statement, indicating that the highest court in the land supports Miranda’s position, makes it seem likely that Miranda will prevail—exactly as a Midpoint should.

After the Midpoint, the SCOR formula requires a Second Pinch Point focused once more on the antagonist, and the Statement does not disappoint. A few lines after the Midpoint, the Statement asserts that the confession attributed to Miranda “uses language inconsistent with [his] . . . education.”[170] It insinuates, in other words, that the police put words into Miranda’s mouth. This makes the failure to issue a Miranda warning seem almost minor. The defense is suggesting that the confession is not authentically Miranda’s. This is a pinch point if ever there was one. The specter of police corruption in terms of eliciting a false confession (even from a person who may have been factually guilty) represents as antagonistic and evil a force as a Hollywood screenwriter could invent.

After the Second Pinch Point, SCOR envisions a Second Plot Point, where the protagonist gets the final thing needed to succeed in the quest.[171] Success will not necessarily materialize, but it might. The Statement, again, delivers. The Second Plot Point describes Miranda’s win at the intermediate appellate court—“[o]n appeal, admission of the confession . . . [was] assigned as error in view of Spano v. New York”—and cites to the U.S. Supreme Court.[172] Miranda thus appears to get the final thing he needs to fulfill his quest: vindication by an appellate court based on a binding, U.S. Supreme Court decision.

The next milestone, the Climax, could go either way. It looks like the protagonist will succeed, but he may not. In this brief, in fact, the Climax does go the other way. Miranda fails in his quest for justice. He loses on appeal at the state high court: “[t]he Supreme Court of Arizona declared [Spano and another case that supported Miranda] . . . inapplicable.”[173] This Climax, where Miranda fails in his quest, is essentially the end of the story, as the Statement’s remaining seven lines simply summarize the state court’s rationale in holding against Miranda. This ending leaves the reader hanging, raises a story question about whether the state court got it right, and invites the U.S. Supreme Court to correct an injustice. Maybe it is up to that Court to finish Act III or maybe it is up to that Court to write a sequel. Regardless, the Statement is a wonderful example of how attorneys can craft the final act, the most difficult one for a legal writer to conceptualize.

B. Other Landmark Briefs

All in all, Miranda’s Statement follows a structure remarkably like the SCOR structure described in this Article. So, too, do the fact statements contained in the subsequent briefs filed in the case.[174] Miranda’s main brief[175] may even do a better job in Act I of humanizing Miranda, probably because the attorneys were working with a more generous page limit and could accordingly develop that section more thoroughly. In any event, Act I in the main brief focuses more obviously on Miranda’s life before his arrest and, in particular, on his quite serious mental health problems. It explains that he dropped out of school in the ninth grade. And it quotes a court-appointed psychiatrist saying that he suffered from an “emotional illness” and describing him as “a schizophrenic reaction, chronic, undifferentiated type.”[176] It includes a fascinating footnote, consisting of Miranda’s bizarre answers to questions about the meaning of various aphorisms, including his view that “people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” means “a person with one woman shouldn’t go to another woman.”[177]

The main brief’s Act III[178] is also more developed than Act III in the certiorari petition, better reflecting a standard movie-like resolution. It focuses on Miranda’s sentence “of twenty to thirty years” for one crime and “of twenty to twenty-five years” for another crime, and ends with the conclusion that Miranda “thus faces imprisonment of forty to fifty-five years.”[179] In short, it shows what the protagonist’s “new normal” is like, instead of focusing, as the certiorari petition did, on the state court’s rationale (which was just an extension of the Climax and not, at least in a standard sense, resolution). The main brief’s Act III shows how the bad event changed the protagonist, just as the final act in a motion picture would.

The stories Miranda’s counsel told, in the certiorari petition as well as in the main brief, show that the three-act structure can work, even when the client does not in any way resemble an archetypal hero. They show how Act I in a defense-side criminal brief might paint a picture of the client’s life before the bad event in somber hues, rather than in the rosy hues Act I would have in a typical civil case. They also show how a lawyer can weave a theme—say, that mentally ill people are especially vulnerable to police intimidation—into the SCOR structure.[180]

They show, finally, how Act III, that most difficult act to write, can be either abbreviated or well developed. Attorneys can end Act III in an abbreviated way as Miranda’s attorneys did in the certiorari petition, by stopping their narrative at the Climax, right after Act II. (In Miranda’s case, this meant discussing the losing appeal at the Supreme Court of Arizona without providing wind-down in the form of a description of Miranda’s new normal.) Alternatively, attorneys can end Act III in a more traditional and well-developed way, presenting both a Climax and a wind-down, as Miranda’s attorneys did in the main brief. There, the story’s Climax was the admission of Miranda’s confession over his counsel’s objection. The wind-down was a picture of Miranda’s new status quo: forty to fifty-five years of prison. Thus, even though the Supreme Court wrote Act III for the Miranda case as a whole, defense counsel wrote it for the shorter story of Miranda’s loss at the state’s high court.[181]

As a final note, this author reviewed many other landmark Supreme Court briefs before settling on Miranda v. Arizona, including (but not limited to) briefs from Cohen v. California, Gideon v. Wainwright, Planned Parenthood Assoc. v. Ashcroft, Shelly v. Kramer, Terry v. Ohio, and Simopoulos v. Virginia. A few of these briefs did not reflect the SCOR structure in any obvious way at all. Others seemed to reflect it, but not in a particularly compelling way. That said, though, the briefs as a whole seemed to be surprisingly adherent to a SCOR-like layout. Their story structures appeared not only to have three acts, but to have standard story milestones, as well. If nothing else, something important often happened at the juncture where SCOR requires a First Plot Point (a quarter of the way into the story), a Midpoint (halfway into the story), and a Second Plot Point (three quarters of the way into the story). Moreover, the briefs often began with Hooks and ended with some attempt to wind the story down.

Of course, the author may have brought her own predispositions to this conclusion. SCOR is not an exact science; it is subjective. The identification of story milestones could be influenced by personal biases, or even wishful thinking. Human beings can unconsciously impose a structure where there is none. One person might see story milestones where someone else would not. At the end of the day, this Article does not purport to be the product of a formal methodology and these comments about landmark briefs are anecdotal. Wishful thinking, though, can only take a story analyst so far. If there truly was nothing substantive where the story milestones should have been, it would be hard to convince anyone, even oneself, otherwise.

IV. CONCLUSION

People are storytellers. As one scholar put it, “we are ‘hard-wired’ for story.”[182] Stories are inherently interesting; they command people’s attention.[183] And stories necessarily involve structure. A random combination of words or sentences is not a story. For lawyers, good storytelling, and mastery of story architecture, is crucial:

Successful resolution of [a] dispute depends, in considerable part, on how well the storyteller imbues the client’s story with narrative coherence, correspondence, and fidelity. And these, in turn, depend upon the storyteller’s grasp of narrative theory and skillful use of the basic techniques of storytelling . . . : sequence, characters, point of view and theory, scene, detail, and tone.[184]

Ultimately, an effective story must have a tripartite, three-act structure. This structure may be embedded in the human psyche or inherent in the nature of language. At minimum, it is so much a part of Western, and probably worldwide, culture and custom, that it is, put plainly, the necessary prerequisite for a story. Its origins do not matter. Regardless whether it is an innate part of the human mind or is simply deeply seated there because people have been telling stories this way for thousands of years, when a lawyer tells a story with this familiar layout, she is playing a tune that resonates with her audience.

True, SCOR seems like a formula, and some readers might be asking, “Why would I want to use a formula? Formulae are bad, right?” Not necessarily. As an initial matter, the premise, that formulae are bad, is probably wrong, at least for legal writing. The legal writer’s main goal is clarity, not creativity. A mystery writer may want to confuse the reader, giving numerous possible suspects, say, in a murder mystery. For lawyers, though, it is different. Lawyers want the reader to follow along every step of the way. They want the reader to understand what they are saying, with perfect clarity, in every section of a memorandum or brief and in every part of an oral argument. They want to fulfill the audience’s expectations. They want to make things easy on the audience.[185] Formulae like IRAC and SCOR help them achieve that goal. They give lawyers an off-the-shelf blueprint for writing analysis, argument, and facts sections. They make the writing process, and the comprehension process (for audiences), easier.

In addition, formulae can be done well or badly. Take today’s most-popular television programs, even the most innovative ones. Make no mistake about it, they are formulaic. Sometimes, the formula is obvious, like in Law & Order, but, sometimes, it is used at such a high level, like in Dexter or Breaking Bad, that viewers never even notice it. In the latter programs, the formula is, as it should be, “invisible and unobtrusive.”[186] Legal writers can use formulae at a high level, too. They need not be ham-fisted in their use of SCOR; they can use it more subtly. And of course, there is no one, precise formula that will work for all attorneys or all lawsuits. SCOR is not the only game in town. Writers have different preferences for both the writing process and story architecture.[187] Nevertheless, for legal writers, just like screenwriters, the three-act structure can be a useful starting point, and it can help simplify the early stages of story development.[188]

Ultimately, the lawyer’s “job [is] to make . . . stories come alive, and we should use all the tools at our disposal, including ones taken from the world of fiction and storytelling.”[189] This does not mean abandoning other tools at our disposal, like precedent, reason, and analysis.[190] Additionally, even though there is considerable leeway for storytelling in the context of litigation,[191] lawyers must not bend the truth. We should present stories in all of their complexity and avoid the temptation to unthinkingly follow a pre-determined narrative at the expense of the truth.[192]

This Article stands for the proposition that “there is a middle ground between abandoning the principles of narrative for cold hard facts and logic and trying to shoehorn . . . clients’ real-life stories into archetype, myth, and heroic journeys.”[193] It contends that SCOR is an appropriate method for lawyers to use because lawsuits are ideal vehicles for the screenwriting approach. “All drama is conflict.”[194] Conflict characterizes every lawsuit. Therefore, every lawsuit involves drama and every lawsuit is at least a candidate for the story architecture discussed here.

See Mark Hughes, Top 10 Most Profitable Movies of 2013 (So Far), Forbes (Aug. 20, 2013, 8:00 AM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2013/08/20/top-10-most-profitable-movies-of-2013-so-far.

Syd Field, Screenplay, The Foundations of Screenwriting, A Step-by-Step Guide from Concept to Finished Script 3 (Delta Trade Paperbacks rev. ed. 2005); Elliot Grove, Raindance Writers’ Lab Write + Sell the Hot Screenplay 26 (2009).

See, e.g., Stephen Paskey, The Law is Made of Stories: Erasing the False Dichotomy Between Stories and Legal Rules, 11 L. Comm. & Rhetoric: JALWD 52, 55-56 (2014) (providing a brief survey of that scholarship).

J. Christopher Rideout, Storytelling, Narrative Rationality, and Legal Persuasion, 14 Legal Writing 53, 53 (2008).

See infra § I (discussing the structural approach to narrative theory).

Although I use the term “screenwriters” throughout this Article, I am really referring to (at least) four groups of people: screenwriters, television writers, novelists, and playwrights.

This Article uses the term “architecture” in the sense used by Betty Flowers in her renowned article on the four stages of writing: the “architecture stage” is where the author “select[s] large chunks of material . . . to arrange them in a pattern that might form an argument. The thinking here is large, organizational, paragraph level thinking—the architect doesn’t worry about sentence structure.” See Betty S. Flowers, Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge: Roles and the Writing Process, 58 Language Arts 834-36 (1979), available at http://www.ut-ie.com/b/b_flowers.html

. Professor Flowers’ article posits that there are four stages of writing and that authors can improve their writing, understand the writing process, and avoid writer’s block by studying them. In a nutshell, the four stages are the “madman” stage (which is chaotic and idea-driven), the “architecture stage” (described above), the “carpenter stage” (where sentence-level wordsmithing occurs), and the “judge” or “janitor” stage (consisting of final edits). The article has influenced many writers, including legal-writing expert Bryan Garner. See Bryan Garner, Legal Writing in Plain English: A Text with Exercises 5 (2001).

384 U.S. 436 (1966).

This Article uses the phrase “narrative theory” in place of “narratology,” i.e., “the branch of knowledge or criticism concerned with the structure and function of narrative and its themes, conventions, and symbols.” Concise Oxford English Dictionary 948 (10th ed. 2002). “Narrative theory” seems to comport more with the modern preference for plain language than “narratology” would.

See, e.g., Linda H. Edwards, Speaking of Stories and Law, 13 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 157, 158-67 (2016) (discussing the words “story” and “discourse,” but also related words such as “narrative,” as well as the practice of choosing definitions generally). For a good discussion of the pros and cons of the word “storytelling” versus the word “narrative,” see Derek H. Kiernan-Johnson, A Shift to Narrativity, 9 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 81, 82 (2012).

Kiernan-Johnson, supra note 10, at 81 (citing Ruth Anne Robbins, An Introduction to Applied Storytelling and to This Symposium, 14 Legal Writing 3, 14 (2008)).

Kenneth D. Chestek, Judging by the Numbers: An Empirical Study of the Power of Story, 7 J. ALWD 1, 3 (2010).

Id. at 9 (citing Kendall Haven, Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startling Power of Story 15 (2007).

Id.

Paskey, supra note 3, at 63.

Kiernan-Johnson, supra note 10, at 86; see also Chestek, supra note 12, at 3.

Robbins, supra note 11, at 12.

See Elizabeth Fajans & Mary R. Falk, Untold Stories: Restoring Narrative to Pleading Practice, 15 Legal Writing 3, 16 (2009) (using term “narrative” in discussion of complaint drafting).

Kiernan-Johnson, supra note 10, at 86.

See Christy H. DeSanctis, Narrative Reasoning and Analogy: The Untold Story, 9 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric 149, 158 (2012) (discussing theme, discourse, and genre); see also Linda L. Berger, How Embedded Knowledge Structures Affect Judicial Decision Making: A Rhetorical Analysis of Metaphor, Narrative, and Imagination in Child Custody Disputes, 18 S. Cal. Interdisc. L.J. 259, 267 (2009) (relying on psychiatrist/psychologist Jerome Bruner’s definition of “narrative”).

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, supra note 9, at 948.

Kiernan-Johnson, supra note 10, at 85; see Concise Oxford English Dictionary, supra note 9, at 948.

Moreover, any negative connotations associated with the word “story” are unlikely to arise due simply to context: this Article takes a serious approach to storytelling. Of course, there may be readers who perceive stories as inherently childish, and scholarship around storytelling as frivolous, but merely substituting the word “narrative” for “story” is unlikely to change their minds. In addition, although the ethical dimensions of storytelling are beyond the scope of this Article, it is essential that lawyers apply the same ethical considerations to legal stories based on the screenwriting paradigm as they would to other such stories.

Various legal scholars have mapped out the scholarly terrain on narrative theory more thoroughly than this Article does. See Chestek, supra note 12, at 7 n.24 & 26 (listing numerous articles and books on the topic); Edwards, supra note 10, at 158-68 (presenting a “conceptual map” of the field). See generally Paskey, supra note 3, at 55-56 (dividing narrative scholarship into three eras).

Edwards, supra note 10, at 159-60.

Paskey, supra note 3, at 55; see also Edwards, supra note 10, at 161 (expanding on Paskey’s work); Binny Miller, Telling Stories About Cases and Clients: The Ethics of Narrative, 14 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 1, 1 (2000) (discussing legal realists).

See Edwards, supra note 10, at 159, 162 (classifying outsider perspectives on narrative theory as jurisprudential at root).

Id. at 163.

Id.

See id. But see Paskey, supra note 3, at 64 (viewing discourse as something more structural than prose: “the distinction between story and discourse is a distinction between content and form,” plot versus presentation, what versus how).

Edwards, supra note 10, at 163.

Id.

Id. at 164.

Chestek, supra note 12, at 2; Edwards, supra note 10, at 159; Rideout, supra note 4, at 54 n.10 (presenting excellent collection of citations to authors who have written about storytelling and persuasion).

Edwards, supra note 10, at 165.

Paskey, supra note 3, at 56.

Id. at 55-56.

Chestek, supra note 12, at 6.

See, e.g., Steven J. Johansen, Was Colonel Sanders a Terrorist? An Essay on the Ethical Limits of Applied Legal Storytelling, 7 J. ALWD 63, 63-64 (2010); Paskey, supra note 3, at 54.

Chestek, supra note 12, at 4; Jeanne M. Kaiser, When the Truth and the Story Collide: What Legal Writers Can Learn from the Experience of Non-Fiction Writers About the Limits of Legal Storytelling, 16 Legal Writing 163, 164 (2010).

Johansen, supra note 39, at 68.

E.g., Chestek, supra note 12, at 29 (studying how judges and others respond to stories); Edwards, supra note 10, at 161 (discussing this branch of narrative theory); Nancy Pennington & Reid Hastie, A Cognitive Theory of Juror Decision Making: The Story Model, 13 Cardozo L. Rev. 519, 520 (1991). Scholars writing from the cognitive perspective have also discussed more practical concerns, arguing, for example, that law professors should integrate storytelling into their classrooms to improve learning outcomes. See, e.g., generally Jo A. Tyler & Faith Mullen, Telling Tales in School: Storytelling for Self-Reflection and Pedagogical Improvement in Clinical Legal Education, 18 Clinical L. Rev. 283 (2011) (discussing clinical classes); Lea B. Vaughn, Feeling at Home: Law, Cognitive Science, and Narrative, 43 McGeorge L. Rev. 999 (2012) (focusing on doctrinal classes).

Steven L. Winter, The Cognitive Dimension of the Agon Between Legal Power and Narrative Meaning, 87 Mich. L. Rev. 2225, 2235 (1989) (quoting Rumelhart & Ortony, The Representation of Knowledge in Memory, in Schooling and the Acquisition of Knowledge 131 (R. Anderson, R. Spiro & W. Montague eds. 1977)).

Edwards, supra note 10, at 160, 172; see also Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 20 (discussing stock stories); Rideout, supra note 4, at 67-69 (same). Some scholars use terms other than “stock story” to refer to concepts that are either identical or very similar. See, e.g., Berger, supra note 20 at 260, 262, 264, 270 (using terms “meta-stories,” “schema,” “scripts,” and “master stories”); Chestek, supra note 12, at 15 (using phrase “deep frame”); Rideout, supra note 4, at 83 (using term “mythos”); see also Gerald P. Lopez, Lay Lawyering, 32 UCLA L. Rev. 1, 3 n.1 (1984) (describing synonyms for “stock stories” and listing various sources on the topic).

Edwards, supra note 10, at 172.

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 20.

Paskey, supra note 3, at 63.

Brian J. Foley & Ruth Anne Robbins, Fiction 101: A Primer for Lawyers on How to Use Fiction Writing Techniques to Write Persuasive Facts Sections, 32 Rutgers L.J. 459, 475 (2001).

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 17.

See Chestek, supra note 12, at 34.

Coherence occurs when ideas flow in logical succession. James C. McDonald, The Allyn & Bacon Sourcebook for College Writing Teachers 179 (1996) (discussing the more specific notion of paragraph coherence); see also Rideout, supra note 5, at 64 (defining story coherence as “how well its parts fit together”).

Rideout, supra note 4, at 64 (citing Robert Burns, A Theory of the Trial 167 (1999)).

Id. at 66.

Steven J. Johansen, This is Not the Whole Truth: The Ethics of Telling Stories to Clients, 38 Ariz. St. L.J. 961, 977 (2006).

See Paskey, supra note 3, at 52 (focusing overall in the entirety of the article on statutory rules, but speaking broadly enough to encompass common-law rules, as well).

Id. at 54.

See Foley & Robbins, supra note 48, at 460-61.

Chestek, supra note 12, at 19-22, 29.

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 4.

Id. (emphasis added).

See Johansen, Not the Whole Truth, supra note 54, at 981 (discussing coherence).

Heidi K. Brown, Breaking Bad Briefs, 41 J. Legal Prof. 259, 275-76 (2017).

Northon v. Rule, 494 F. Supp. 2d 1183, 1188 (D. Or. 2007).

Brown, supra note 62, at 261-62.

Id.

Id. at 276.

Johansen, Not the Whole Truth, supra note 55, at 981; see also Susan Chesler & Karen J. Sneddon, Tales from a Form Book: Stock Stories and Transactional Documents, 78 Mont. L. Rev. 501 (2017) (focusing on transactional writing).

Lopez, supra note 44, at 9-10.

Kaiser, supra note 40, at 163-77 (criticizing stock stories as not always meshing with the real-life stories).

Obviously, many of the stories underlying lawsuits, perhaps even all them, are unpleasant.

Brooks Landon, Building Great Sentences (book on CD by Great Courses) (quote available at http://www.penguin.com/ajax/books/excerpt/9781101614020).

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 15-16.

Chestek, supra note 12, at 34; see also Foley & Robbins, supra note 48, at 459 (“Don’t bore your reader.”).

Brown, supra note 62, at 261.

See Flowers, supra note 7.

Foley & Robbins, supra note 48, at 462.

Field, supra note 2, back cover.

Id. at 14.

Id. at 16.

Brown, supra note 62, at 262.

Id. at 263.

“A lawyer who chooses to use stories to persuade may look to the same ethical principles to which she has always looked.” Johansen, Colonel Sanders, supra note 39, at 84.

Bryan Garner, Advanced Legal Writing & Editing 45 (Rev. ed. 2002) (emphasis added).

See Craig Batty & Zara Waldeback, Writing for the Screen 31 (2008) (defining “story” in the context of a discussion on screenwriting); Foley & Robbins, supra note 48, at 475-76 (discussing stories in the context of legal writing and observing that “[t]he common way of organizing a story is, as Aristotle wrote almost 2,500 years ago, in three parts: the beginning, the middle, and the end”); see also Aristotle, Poetics VII (335 BCE) (“A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end.”).

Paskey, supra note 3, at 64.

See Flowers, supra note 7.

Paskey, supra note 3, at 64.

Id. at 66.

Miller, supra note 26, at 12-13.

Jack Epps, Jr., Screenwriting Is Rewriting: The Art and Craft of Professional Revision 86 (2016).

Freddie Gaffney, On Screenwriting 92 (2008).

For example, the first act could be seen as tying a knot, the second as tightening it, and the third as untying it, or the first act as inspiration, the second as craft, and the third as philosophy. David Howard, How to Build a Great Screenplay, A Master Class in Storytelling for Film 255 (2004). Another way of viewing the three acts is to: “[g]et your hero up a tree; throw rocks at him; [and] get him down from the tree.” Epps, supra note 91, at 86 (quoting George M. Cohan, a Broadway playwright).

E.g., Antony G. Amsterdam & Jerome Bruner, Minding the Law 113-14 (2000); Edwards, supra note 10, at 175 & n.124; Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 18-19 (presenting five parts of a story and then reducing them to “steady state . . . conflict and . . . resolution”); Cathren Koehlert-Page, Like A Glass Slipper on A Stepsister: How the One Ring Rules Them All at Trial, 91 Neb. L. Rev. 600, 647 (2013) (discussing seven parts to a story, but also talking about three acts).

Howard, supra note 92, at 256.

Id. That said, there may be different story paradigms beginning to emerge in Hollywood. See Field, supra note 2, at 7-8; see also Grove, supra note 2, at 27 (discussing Field’s open-mindedness about this phenomenon).

E.g., Larry Brooks, Story Engineering: Mastering the 6 Core Competencies of Successful Writing 146 (2011). Some writers have different names for Act I, but the function of Act I is still to describe the status quo before the story begins in earnest. See, e.g., Gaffney, supra note 91, at 93 (describing Act I as the “Exposition”).

Brooks, supra note 96, at 147. Act I “establishes the characters’ ‘normal’ abilities in their ‘normal’ situation.” Gaffney, supra note 91, at 93 (2008). Legal scholars agree. See, e.g., Chestek, supra note 12, at 11; Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 18.

E.g., Field, supra note 2, at 24-25. Some writers have different names for Act II, but its hallmark is still confrontation. See, e.g., Gaffney, supra note 91, at 93 (describing Act II as the “Development”).

Gaffney, supra note 91, at 92 (discussing the need for the protagonist to have setbacks in order to make things interesting).

E.g., Field, supra note 2, at 26. Some writers have different names for Act III, but its function is always to wind the story down. See, e.g., Gaffney, supra note 91, at 93 (describing Act III as the “Solution”).

See Field, supra note 2, at 26.

Gaffney, supra note 91, at 94.

Field, supra note 2, at 3; see Berger, supra note 20, at 267 (using terms “steady state . . . crisis . . . redress”).

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 19.

Id.

Field, supra note 2, at 29.

Rideout, supra note 4, at 58-59.

Fajans & Falk, supra note 18, at 19 (citing Amsterdam & Bruner, supra note 93, at 115); Rideout, supra note 4, at 55, 57-58.

Field, supra note 2, at 8.

Gaffney, supra note 91, at 92.

Field, supra note 2, at 21.

Gaffney, supra note 91, at 92.

Brooks, supra note 96, at 166.

Id.

See id. (“the earlier the hook, the better”); see also generally Maureen Johnson, You Had Me at Hello: Examining the Impact of Powerful Introductory Emotional Hooks Set Forth in Appellate Briefs Filed in Recent Hotly Contested U.S. Supreme Court Decisions, 49 Ind. L. Rev. 397 (2016) (taking an in-depth look at the use of hooks in legal briefs).