Many of today’s law school graduates lack the practical skills that they need to thrive as practicing lawyers.[1] As a result, it is incumbent on law schools—and, specifically, legal writing programs—to redouble their efforts to prepare law students for the realities of modern legal practice.[2] And perhaps no feature of modern legal practice has been more striking than the “meteoric rise of email as a means of professional Communication.”[3] Driven by its speed, efficiency, and convenience[4] over the traditional, formal memorandum,[5] email is now the most popular way for lawyers to provide legal advice.[6] As a result, teaching effective email practices is no longer optional; “students must learn how to write effective emails to a legal audience to be law practice-ready.”[7]

After a somewhat slow start, email has received increased attention in legal writing scholarship and pedagogy in recent years, and email assignments have become a mainstay in many first-year legal writing programs.[8] But while there have been many suggestions about the types of email assignments that could be used, there has been little principled discussion of which types of email assignments should be used and what purposes the different types of email assignments serve.[9]

This Article attempts to contribute to this discussion with several specific goals. First, the Article reiterates the point that email assignments should be an integral part of the first-year legal writing curriculum. Second, it establishes a very basic taxonomy of e-mail assignments and examines the benefits of each type. Third, it argues that relying solely on email assignments that are set in the context of a larger memo assignment may miss opportunities to help students fully develop specific research, analytical, and writing skills that they are likely to need in practice. Lastly, the Article suggests a specific type of email assignment—the “Procedural E-memo”—as an efficient tool for helping students develop a range of practical research, analytical, and writing skills that they are likely to use in sending emails in practice.

While the increased focus on email communication in the legal writing curriculum is a positive development, legal writing faculty must avoid thinking that “e-memos” are a monolithic category. Rather, legal writing faculty should recognize that there are different types of email assignments—and each has important, but distinct, pedagogical benefits. Consistent with the American Bar Association’s focus on student learning outcomes, legal writing faculty should be thoughtful about what kinds of e-memo assignments they are incorporating—and to what ends.[10] By doing so, legal writing faculty can best equip their students with a range of practical skills that they will need to hit the ground running in today’s practice.

I. EMAIL IN MODERN LEGAL PRACTICE, AND THE DEBATE OVER ITS PLACE IN THE LAW SCHOOL CURRICULUM

Over the past two decades, substantive emails, or “e-memos,” have replaced traditional, formal legal memos as the most popular way for attorneys to deliver legal advice.[11] This shift spurred scholarly debate about whether e-memos constitute a distinct legal writing genre and about the email’s place in the first-year legal writing curriculum.[12] With more and more legal writing programs incorporating email into the first-year curriculum, this Section argues that it is time for the debate about email in the first-year curriculum to move on from the question of whether to teach email at all to the question of how to do so in a thoughtful, pedagogically sound way.

Today’s lawyers—and new lawyers in particular—are beset by emails. Beginning with Kristen Robbins-Tiscione’s 2006 survey of Georgetown University Law Center alumni,[13] studies of practicing attorneys have revealed the central role that email plays in daily lives of today’s lawyers.[14] And email’s prevalence permeates all types of legal jobs, practice areas, and office sizes.[15] As a 2016 ethnographic study of law firm associates summed up, “[r]eading and ultimately responding to email occupie[s] a great deal” of young attorneys’ time.[16]

Email’s rise has changed the way that lawyers deliver legal advice. Today’s lawyers simply are not writing many traditional, “formal” memoranda that comprise the bulk of the traditional legal writing curriculum.[17] Instead, “email memos have become the predominant means of communicating analysis between lawyers.”[18] Given the centrality of email in modern legal practice, learning to communicate effectively in email form is a necessary skill for new lawyers.[19]

But despite email’s ubiquity in the modern law office, the legal skills academy was somewhat slower to integrate email instruction into the legal skills curriculum. While Kristen Tiscione’s 2006 survey had revealed that more than 90% of respondents were using substantive email to provide legal advice to clients,[20] a 2013 survey of general legal writing textbooks showed that only 35% discussed “email memos” as a distinct writing category.[21] And a 2011 review showed that of the sources that did cover emails, most focused on “issues of security, etiquette, and professional tone”; “very few [were] about the form and content of electronic communication.”[22] Some of the delay in incorporating email into legal writing courses may have been attributable to mere curricular inertia. But the rise of email also spurred academic debate about whether “e-memos” represent a genre separate and apart from the traditional, formal memorandum and about whether email belonged in the legal writing curriculum at all.

One view—advocated most prominently by Kristen Tiscione and Ellie Margolis—suggests that e-memos constitute a new and distinct legal writing genre.[23] These commentators posit that the change in medium—from paper to email—creates a fundamental shift in the way that legal analysis is conducted and communicated.[24] These scholars argue, for example, that the comparative informality of the e-memo and its lack of prescribed elements creates a more organic format, where writers are free to combine traditional sections like the facts, brief answer, question presented, and conclusion in ways that are more “accessible, efficient, and appropriate.”[25] Tiscione and Margolis also suggest that the medium of email—with its known audience and an expectation of an “ongoing conversation”—creates an opportunity to better anticipate and respond to the reader’s needs.[26] Some commentators have even questioned the ongoing relevance of teaching the traditional, formal memorandum in light of its relative scarceness in modern practice.[27]

The opposing view—advanced by Kirsten Davis—argues that e-memos are not a distinct genre but, instead, that they fall within the flexible confines of the traditional memo.[28] According to Davis, “it is the complexity of the question presented, and not the type of media that should dictate the structure of the memo.”[29] Teaching e-memos as a distinct genre, Davis warns, might encourage students to oversimplify legal analysis to the point that it fails to adequately explain the issues to the reader.[30] And she argues against abandoning the “traditional” memorandum because it serves important pedagogical goals by helping students build the capacity for complex legal analysis.[31]

These discussions about the potential differences between “traditional” memos and “e-memos” were necessary early steps in the development of a shared pedagogy about email’s place in legal writing. But, at this point, the debate over whether e-memos constitute a separate genre is largely unnecessary and, potentially, unhelpful for the academy for two reasons.

First, to the extent the debate focused on the question of whether email memos should have a place in first-year legal writing at all, that question is increasingly being answered in the affirmative. In the years since the traditional-vs.-e-memo debate emerged, “email communications have increasingly become part of the legal writing curricula,”[32] and there appears to be a broad consensus that email assignments should be incorporated into first-year writing courses. In just three years—from 2012 to 2015—the proportion of legal writing programs that assigned e-mail memos in the first year rose from less than half (47%) to nearly two-thirds (65%).[33] So with the clear trend in favor of incorporating email memo assignments into the curriculum in some fashion, the question is no longer “Should we include email assignments in the first year,” but, rather, “How can we do so in the most effective way?”

Second, as discussed in greater detail later in this Article, the traditional memo-vs.-e-memo debate oversimplifies the issue by treating e-memos as a monolithic category. In reality, there are different types of e-memos—just as there are different types of traditional, formal memos. Some involve simple legal issues that call for short, simple responses; some involve complex matters calling for complex analysis.[34] Despite the email format, some e-memo assignments look much more like traditional, formal memos in terms of the sources used and the type and complexity of the legal analysis. By contrast, some e-memos can look completely different in their form, complexity, and type of analysis.

Herein lies the problem: if legal writing professors simply incorporate “e-memo” assignments without considering the distinctions within that category, they may be missing opportunities to develop a broad range of practical emailing skills that students are likely to use in practice. But while many commentators have discussed various ways of using specific email assignments, there has been little recognition—let alone exploration—of the different types of e-memo assignments and the pedagogical benefits that each type might serve. To help address this gap, the following Section surveys the existing literature on e-memo assignments to create a basic taxonomy of e-memo assignments.

II. A BASIC TAXONOMY OF E-MEMO ASSIGNMENTS

The growth of email in legal writing programs has led to growth in the literature surrounding email pedagogy. Legal writing commentators have described various ways in which email could be incorporated into the first-year curriculum. Broadly speaking, these assignments can be grouped into two categories: “Summary” E-memos and “Standalone” E-memos.[35]

On one hand, legal writing faculty describe using email as an add-on in the context of a longer memo or brief assignment—one that students have already researched or even written. Because these assignments require students to summarize information that was learned in the course of completing another, more complex research or writing task, I refer to these as “Summary E-memo” assignments. Perhaps the simplest form of a Summary E-memo assignment asks students to take the longer, more complex analysis from a formal memorandum and condense it into a shorter, simpler, email format.[36] Another type of Summary E-memo assignment involves having students summarize their research findings as an intermediate step before they have finalized a memo or brief.[37] For example, Ellie Margolis recounts using an email assignment in which she told students that their supervising partner was “going to meet with the client and needed an overview of what they had found so far, even though I knew they hadn’t yet completed the full memo.”[38]

The fact that Summary E-memo assignments are given as part of a larger writing project has two important consequences. First, it Summary E-memo assignments rely on the same underlying research sources as the larger assignment—which, in the first-year curriculum, means predominantly judicial opinions.[39] Second, because the Summary E-memo involves the same legal issues as the larger assignment, the type of legal reasoning involved mirrors the type of legal reasoning required for the larger writing project. In the first-year curriculum, this generally means an IRAC-style analysis requiring the synthesis of rules from various judicial opinions and other sources, followed by an application of those rules to a specific set of facts.[40]

On the other hand, legal writing faculty have also described short email assignments that require students to complete limited independent research and write an email response on a legal issue that they have not previously worked on. Because they are independent of any larger assignment, I refer to these types of assignments as “Standalone E-memo” assignments. For example, Kristen Tiscione suggests a “short e-mail assignment that requires [students] to conduct limited research and draft an e-mail to their supervising attorney within ninety minutes.”[41] Similarly, Sheila Miller describes a “short in-class research exercise where the students are given a legal question and instructions that they have to use free internet sources to get the answer.”[42]

To allow students to research and write a complete and accurate email response, the legal issues involved must, necessarily, be relatively simple. This desired simplicity is generally achieved by using legal questions that involve clear rules (either from enacted sources or from case law) with little need for more complex rule synthesis or for intensive fact-based application. For example, Amy Vorenberg and Margaret McCabe describe a short, procedurally focused memo assignment, requiring students to describe the steps required to evict a tenant under state law.[43] And Charles Calleros describes multiple ways in which short, simple standalone assignments could be used, including “quick research to support negotiations or other transactional work” or a “short, simple office memo assignment, such as the effect of a new statute on prior law, without the facts of a new dispute.”[44]

III. ASSESSING THE BENEFITS OF SUMMARY AND STANDALONE E-MEMO ASSIGNMENTS

As the preceding Section demonstrates, there has been scholarly discussion about what types of email assignments legal writing faculty can integrate into the first-year curriculum. But, to date, there has been little principled discussion about the relative benefits of the different types of email assignments. Ideally, faculty would incorporate a range of email assignments, and students would have multiple opportunities to practice communicating legal analysis in emails in a variety of contexts.[45] Indeed, this is one of the consistent themes that comes out of surveys of practicing attorneys: the recommendation for more frequent, shorter assignments to prepare students for the tasks they are most likely to have as new attorneys.[46] But the reality is that first-year legal writing classes are already overloaded with content, making it difficult to incorporate numerous email assignments.[47] And eliminating traditional, complex memo and brief assignments is also problematic, as those assignments build critical skills in complex legal reasoning.[48]

As a result, some legal writing faculty—strapped for time—may choose to use only a Summary E-memo assignment, perhaps believing that they have “checked the box” by including an e-memo assignment. And, to be sure, that would be better than having no email assignments at all. But it would miss out on opportunities to develop some real-world skills, potentially leaving students with an incomplete skillset for today’s practice.

A. Summary E-memo assignments can efficiently introduce email skills and enhance students’ analytical abilities.

Summary E-memo assignments are valuable additions to the curriculum that benefit students and faculty in several ways. First, they expose students to the process of summarizing complex legal analysis in email form—something students will no doubt have to do for their superiors or clients on occasion. Given the decline of the traditional, formal memorandum, even when lawyers are called on to deliver complex legal analysis, much of that advice is being delivered in a condensed email format.[49] Second, Summary E-memo assignments provide an opportunity to learn and practice effective and professional email skills by exposing students to issues of tone, formality, organization, formatting, and the ethical issues surrounding the use of email to deliver legal advice.[50]

Third, these types of exercises can improve students’ analytical reasoning skills. As Katrina Lee has argued, having students summarize their research findings or distill the argument from a longer memo or brief into a short email can help the students sharpen their analytical abilities, which students can then apply back to the more complex writing project.[51] More specifically, Lee suggests that the “freer, more liberated” process of writing emails “may offer benefits to students’ learning process similar to that of free writing and oral presentation.”[52]

Lastly, Summary E-memo assignments offer efficiencies for both faculty and students.[53] For faculty, using these types of assignments avoids the difficult task of devising new problems and, instead, leverages the time already invested in creating prompts for larger memo or brief assignments. And for students, using legal issues that they have already researched or written about, reduces the number of new legal issues that students need to research, learn, and explain in a first year that is already brimming with legal topics.

Given these efficiencies that Summary E-memo assignments provide for both students and faculty, legal writing professors might be tempted to rely solely on Summary E-memos to introduce emailing skills. Because Summary E-memo assignments serve important pedagogical goals, that would be better than using no email assignment at all. But relying only on Summary E-memo assignments could leave students with an incomplete skillset for today’s practice.

B. Standalone E-memos offer important opportunities to build a more complete range of analytical, research, and skills to more fully prepare students for practice.

Compared to Summary E-memo assignments, short, simple, Standalone E-memo assignments offer distinct benefits that can help students build real-world practice skills. First, Standalone E-memo assignments may better approximate the shorter, simpler emails that many of today’s lawyers are writing. Second, simple Standalone E-memo assignments provide an opportunity to free students from the strict IRAC-based reasoning that dominates the first-year legal writing curriculum. Lastly, the independent research inherent in a Standalone E-memo assignment provides an ideal opportunity to build crucial, real-world online research skills.

1. Shorter, simpler, time-sensitive emails reflect today’s modern legal practice.

Today’s lawyers are not only writing more emails; evidence suggests that they are writing shorter and more straightforward emails. Perhaps spurred on by the ease and relatively low cost of exchanging emails, today’s lawyers are busy—generally working on a large number of shorter assignments, rather than small numbers of longer assignments. For example, in Sheila Miller’s 2014 survey of practicing attorneys, more than one-third of respondents reported handling more than twenty “matters” in a typical week.[54]

For many of today’s lawyers, this translates into much time spent providing relatively short answers to legal questions. Miller’s survey also showed that more than one-third said they send “often,” “very often,” or “always” draft “bottom line answer” memos that address the “legal question with little or no analysis.”[55] And 88% of respondents reported that length of a typical memo was one to five pages.[56] Anecdotal evidence from attorneys reinforces these ideas. For example, in reporting the results of a survey of Georgetown alumni, Kristen Robbins-Tiscione includes a comment from a participant that “most of my ‘memos’ are short emails. I haven’t written a long memo in years, but I am constantly asked to write one-pagers on issues.”[57] And in another article on the value of teaching email in the first semester, Charles Calleros relates a conversation with a transactional attorney whose associates “typically support her by sending e-mail messages conveying brief research findings in response to questions, limited in scope and requiring quick responses, which pop up during negotiations.”[58]

The prevalence of shorter, simpler emails is also consistent with my recent legal experience as a litigation associate in a large law firm before starting to teach legal writing full-time—an experience I have drawn on in trying to design realistic assignments.[59] The emails I wrote often dealt with relatively straightforward substantive matters, procedural questions surrounding litigation, or some combination of the two, such as the steps for having an appellate court relinquish jurisdiction to correct a scrivener’s error in a lower-court judgment or the timeline for responding to an in rem civil forfeiture action.

The limited scholarship on real-world emailing practices, coupled with my own experience, suggests that many of the emails that today’s lawyers are sending share several common traits—traits that distinguish them from the types of Summary E-memos described above and often assigned in first-year legal writing:

Many of today’s legal emails are rule-focused, with little application. Many emails in practice deal with relatively clear rules—either substantive or procedural—meaning that there is less need for extensive application of the rules once the right ones are found. To be sure, such emails often require sorting through multiple layers of overlapping rules—for example, weaving state procedural rules with a particular court’s local rules and, potentially, additional rules from a court division, individual judge, or clerk. But they often do not require synthesizing rules from judicial decisions or engaging in comparison to a known set of facts. Rather, they prioritize clarity and organization over analytical rigor.

Many of today’s legal emails have right and wrong answers. The relative brevity of today’s emails suggests that many of them concern legal issues with straightforward rules and clear-cut answers. The deadline for filing a claim in an in rem civil forfeiture proceeding is not “probably” one date or another. And the steps and forms necessary to evict a tenant are not properly characterized as “best guesses.” There are definitive answers to those questions, and the consequences for getting them wrong can be dire. As a result, many of today’s real-world emails demand high-confidence responses that readers can instantly rely on without having to extensively review supporting materials.

Many of today’s legal emails rely on research sources unfamiliar to law students. Today’s “bottom line” emails often rely on research sources different from those law students most commonly use. For example, procedural questions may turn on unfamiliar sources of enacted law—such as court local rules or judges’ administrative or standing orders—that may be more conveniently found on a given court’s official website than on Lexis or Westlaw, if they are available on subscription databases at all.[60] And for practicing attorneys, jurisdiction-specific forms and the previous work of other attorneys who have done similar things can be valuable resources.[61] So legal blogs, firm white papers, and actual filings available through PACER or Bloomberg Law can be valuable tools—at least as a jumping-off point.

Many of today’s legal emails are time-sensitive. Perhaps driven by deadlines or by the perceived ease of drafting an email, today’s real-world email assignments often come with quick turnarounds; clients and supervising attorneys expect fast answers.[62] Response times are often measured in hours—not the days that a traditional first-year legal writing assignment might come with.[63]

2. Standalone E-memo assignments offer an opportunity to free students from rote, IRAC-centric, predictive reasoning.

Using a Standalone E-memo assignment can allow students to practice something besides the full-blown, IRAC-style legal analysis that dominates the first-year legal writing curriculum.[64] First-year legal writing assignments tend to deal with somewhat ambiguous legal issues. Students examine multiple sources—generally cases—to synthesize a rule and then apply that rule to a novel set of facts to predict a likely outcome.[65] Students can be conditioned to think that their analysis will usually be framed as a best guess or a probability—not a certainty.[66] A Summary E-memo assignment that asks students to condense a longer predictive memo into an email may allow students to escape the strictures of the traditional memo format—by, for example, eschewing formal “Question Presented,” “Short Answer,” or “Conclusion” sections.[67] But it likely still involves the complex task of synthesizing and explaining legal rules and then applying those to a given set of facts to predict a likely outcome. And even if students are already familiar with the subject matter, they must think through how best to preserve or re-package their content so that a reader can understand the complex interaction between the existing legal rules and the facts of the particular case. So students may simply be rehashing the same reasoning skills that students have already practiced on the broader memo assignment.

By contrast, shorter, simpler, Standalone E-memo assignments that focus on clear, enacted rules can offer students something different, providing several pedagogical benefits. First, focusing on shorter, simpler rules helps students develop better awareness of the need to tailor the depth of analysis to fit the circumstances—a topic that may be given short shrift in many legal writing courses.[68] Second, clear, simple email assignments allow students to become comfortable with taking confident positions on legal questions—something many novice legal writers struggle with.[69]

Lastly, using clearer rules allows students to focus specifically on developing skills in effective email drafting without being distracted by the substance of more complex legal analysis. Cognitive load theory suggests that students’ ability to learn is hindered when they are asked to hold too much information or complete too many complex tasks simultaneously.[70] Summarizing a traditional, IRAC-style analysis in a Summary E-memo assignment presents such a problem: students must simultaneously decide how to apply newly learned lessons about effective email drafting and think about how best to preserve the essence of the complex rule explanation and application in a shorter email form. By contrast, a Standalone E-memo assignment that uses simpler, rule-focused issues frees students from worrying about applying those rules to a set of facts. This can reduce cognitive load and allow students to focus more squarely on effective emailing skills.[71]

3. Standalone email assignments offer an opportunity to build skills in locating and using novel, online sources of law.

While Summary E-memo assignments rely on the same sources of law and the same research tools that the students are using for their larger writing assignment, Standalone E-memo assignments require students to do novel research, offering opportunities to help students develop practical research skills—particularly with efficient and cost-effective online research tools.

To be practice-ready, law students need to be able to find and evaluate a broad range of legal sources.[72] A short Standalone E-memo assignment provides an ideal opportunity to move beyond the traditional sources of law in first-year legal writing courses—judicial opinions and statutes—and branch out into different sources of enacted law.

More specifically, the opportunity for novel research creates a chance for students to develop skills in using free online research tools. Today’s lawyers must be able to use a range online tools—both subscription-based and free—to conduct cost-effective research.[73] Today’s attorneys commonly use free online sources in their legal research—both for effectiveness and to avoid charges on paid subscription services like Lexis, Westlaw, or Bloomberg Law.[74] So new attorneys need to be familiar with using these tools.[75] While some faculty might assume that today’s tech-savvy law students are competent online researchers, many still need help learning to locate and evaluate free online sources for both primary and secondary authority.[76] And because they become accustomed to having unlimited access to subscription legal databases in law school, new attorneys may not be as inclined to use free online sources as they should.[77] A Standalone E-memo assignment offers an efficient way to integrate these online research skills, particularly by using free, online sources of law.[78]

IV. THE “PROCEDURAL E-MEMO”: A CHANCE TO EFFICIENTLY DEVELOP REAL-WORLD RESEARCH AND EMAILING SKILL

As the above Section has shown, Standalone E-memo exercises serve important pedagogical goals different from those served by Summary E-memo exercises. In light of this—and in reflecting on my own practice experience—I set out to create a Standalone E-memo assignment that would allow students to build skills that they are likely to need early in their careers when navigating the multitude of short, quick-turnaround email assignments they are likely to face in practice.

To avoid overwhelming students with work outside of class, the assignment would have to involve a relatively simple legal issue. And it would have to combine multiple skills in an effort to be maximally efficient in a first-year legal writing course “that is already crowded for time and must teach a multiplicity of basic skills.”[79] Specifically, the goal was to create an email assignment that would

-

Require students to use novel and free online sources of enacted law;

-

Emphasize relatively clear, rule-based, action-oriented advice over complex analysis;

-

Promote professional, effective email practices;

-

Simulate real-world conditions, including realistic time constraints.

The assignment is modeled on my real-world experiences with sending short, clear, action-oriented, procedurally focused emails in the litigation context—leading me to nickname this type of assignment a “Procedural E-memo.” The following sections describe the goals of the assignment, which are designed to take full advantage of the distinct pedagogical benefits of Standalone E-memo assignments within a single class session—an important consideration for legal writing professors struggling to add content to an already-full curriculum.

A. Goals and learning outcomes that may be met by the “Procedural E-memo” assignment.

The assignment has two broad categories of student learning outcomes. First, the assignment seeks to help students develop proficiency in locating and evaluating free, online sources of primary procedural law—in this case, federal court local rules. Second, the assignment aims to help students build skills in drafting effective emails that prioritize clarity and readability over IRAC-style analytical rigor.

1. Build real-world online research skills and familiarity with novel sources of law.

As noted above,[80] students need to become familiar with a variety of legal sources and research tools. And selecting sources of law that are not available on fee-based legal databases allows students to practice time-saving and cost-effective use of free, online resources.[81] Any number of online sources of law could be used to craft a simple, rule-focused Standalone E-memo assignment, such as agency guidance documents,[82] local ordinances,[83] patents,[84] or executive orders.[85]

But one potential source seems particularly well-suited for providing straightforward, action-oriented email assignments: federal court local rules. Such local requirements are widespread in litigation practice,[86] and their overlap with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure makes them approachable to first-year law students studying civil procedure. Lastly, local rules are easily available through individual court websites, encouraging students to use their online research skills to locate the appropriate webpages and then navigate them to locate the relevant information.[87]

With these principles as a backdrop, specific student learning outcomes for the assignment include:

-

Locating federal district court local rules on the court’s website in an efficient manner;

-

Identifying specific local rules provisions that are relevant to a client’s problem; and

-

Evaluating the interaction between the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and district court local rules.

2. Instill effective, professional emailing practices.

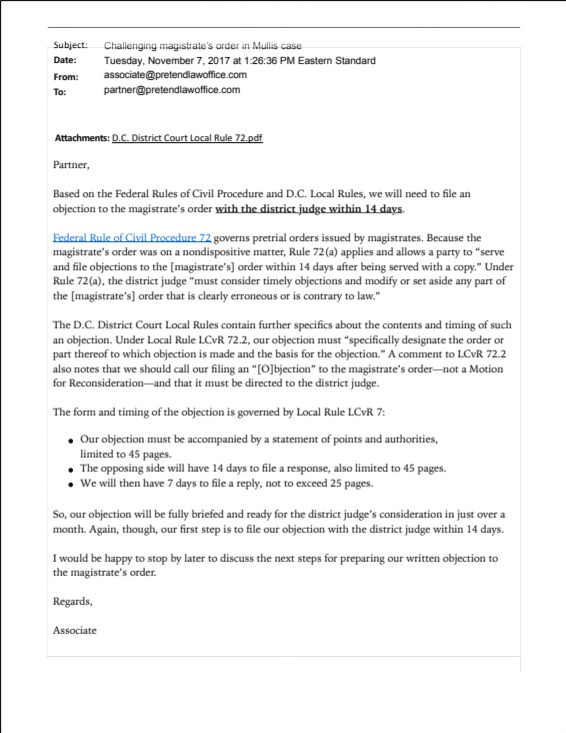

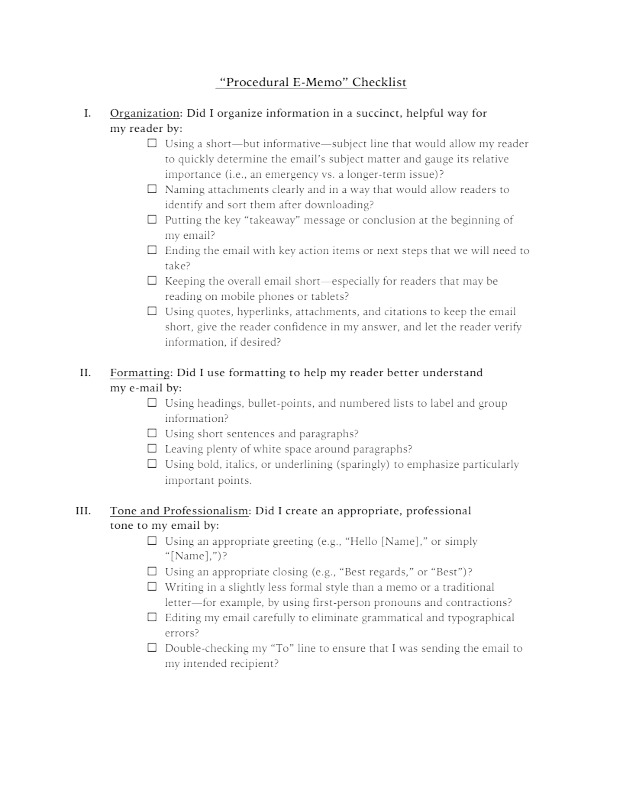

The other main goal of the assignment is to help students build their skills in conveying legal advice in effective emails. While there are a number of topics that could be covered, the most salient student learning outcomes can be grouped into several categories: (a) organization and awareness of the reader’s needs, (b) formatting considerations, and (c) etiquette, professionalism, and ethical considerations.

Organization and awareness of the reader’s needs. As with any piece of legal writing, writers must be aware of the reader’s needs, and readers have their own unique expectations for reading an e-memo.[88] Attorneys and clients will rely on Procedural E-memos to take very specific actions that they must have confidence in. So students should be mindful of the reader’s need for quick, clear, and actionable answers. In terms of student learning outcomes, students should demonstrate the ability to

-

Use informative—but concise—subject lines to allow readers to quickly determine the relevance and importance of the information[89];

-

Employ thoughtful naming practices for attachments to help readers track files after downloading them[90];

-

Use key words in subject lines and messages to facilitate electronic searching later[91];

-

Put the takeaway point or conclusion of the email at the beginning[92];

-

Begin or end the email with clear, actionable next steps[93];

-

Keep the overall length of the email short[94]—being mindful that many readers will be reading emails on smartphones[95]; and

-

Use quotes, hyperlinks, attachments, and citations to deliver high-confidence answers that a reader can immediately trust.[96]

Formatting considerations. In recent years, Legal writing scholars and commentators have explored the impact of formatting on the effectiveness of legal writing.[97] And these formatting considerations are doubly important for electronic documents, including emails, where the inherent distractions of digital devices[98] and smaller cell-phone screens[99] present their own challenges to a writer trying to convey information to a reader. In terms of specific learning outcomes, students should be able to use formatting elements that make for effective emails, including

-

Liberal use of headings, bullet-points, and numbering[100];

-

Shorter sentences and paragraphs[101];

-

Thoughtful spacing between paragraphs to create “cushions” of white space[102]; and

-

Strategic use of bolding, italics, and typography to emphasize key points.[103]

Etiquette, ethics, and professionalism. Lastly, the assignment also offers a chance to remind students about general email etiquette, as well as the more specific ethical and professionalism considerations that surround the use of email in legal practice. While it may be tempting to think that today’s students’ extensive exposure to email has led them to develop good email habits, “law professors cannot assume from students’ familiarity with email that they know how to use it professionally.”[104] So specific student learning outcomes could include the ability to properly use traditional correspondence practices, such as greetings and closings,[105] and the ability to produce a polished, error-free email that reflects the lawyer’s obligation to communicate in a professional manner.[106] At the same time, email messages generally call for slightly less stylistic formality—for example, in the use of contractions[107] or the use of first names in greeting, where appropriate.[108] Students can also be introduced to the potential ethical issues involved with forwarding and replying to email, inadvertent disclosure, and confidentiality.[109]

B. The “Procedural E-Memo” Assignment

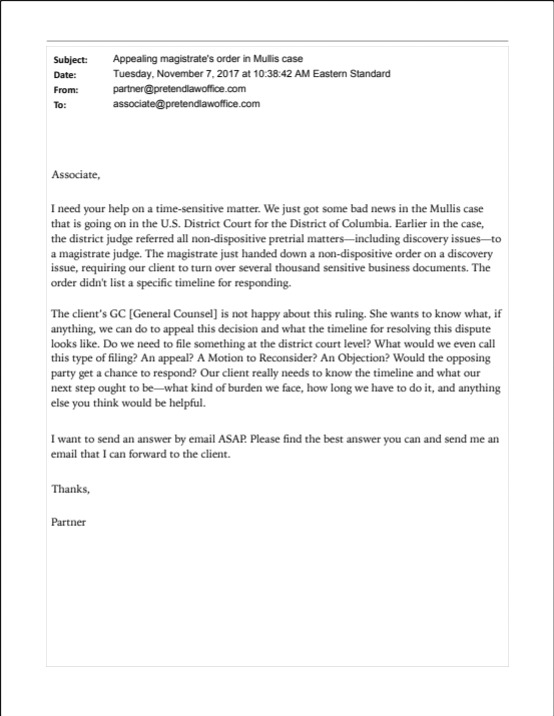

Introductory lecture. (15-20 minutes) The assignment begins with a brief lecture that touches on (a) the key organizational, formatting, and ethical considerations described above, (b) the concept of local court rules, and (c) commonly used non-subscription-based research sources, including government websites, unofficial codes, dockets, and legal blogs. After that, the students are presented with an email from a partner, asking the student to determine the answer to a litigation-related procedural question in federal court. The online course management system that we use at our law school allows me to pre-schedule an email to arrive in the students’ inboxes at a particular time. So when we are finished with the lecture, students check their inbox to see an email from a partner.[110] Having the students receive their prompt via email—instead of through a paper copy or a PowerPoint slide—lends an air of realism to the assignment, an important consideration, given that the assignment is designed to simulate a real-world research and writing task. Providing the prompt via email also allows the professor to model effective (or ineffective) email practices that can provide a jumping-off point for a discussion or for a point of comparison.

Subject matter. As noted above, district court local rules provide fertile grounds for a procedurally focused, Standalone E-memo assignment.[111] While any number of procedural questions are possible, two are particularly well suited to this assignment: (1) describing the process for filing un-redacted documents under seal,[112] and (2) describing the timeline and procedure for objecting to a magistrate’s order in a discovery dispute.[113] These two legal issues work well for a couple of reasons. First, while both issues are relatively simple, they require students to weave together multiple, overlapping provisions in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and federal local rules to deliver a complete answer. Second, while students may be generally familiar with federal rules from a Civil Procedure course, the specific rules implicated by these two issues—Rule 5.2 and Rule 72(a), respectively—are a bit too esoteric to be covered in much detail in most courses. The problems are set in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia—a place where many of our school’s students are likely to practice—although many other jurisdictions likely have similar rules.

Small-group research and discussion. (15-20 minutes) After they read through the prompt, the students spend 10-15 minutes in pre-assigned research groups looking for the answer, using any online resources they like. Students then reconvene and discuss their findings in a class-wide discussion. First, students are prompted to discuss their research methods—what sources they used, how they located them, and how they decided they were reliable. Then, they discuss the substance of their findings, with the goal of reaching a class-wide consensus on the relevant rules and the answer to the question. Because the issue is procedural in nature, the answer should be clear, and the students should be able to have high confidence in their answers.

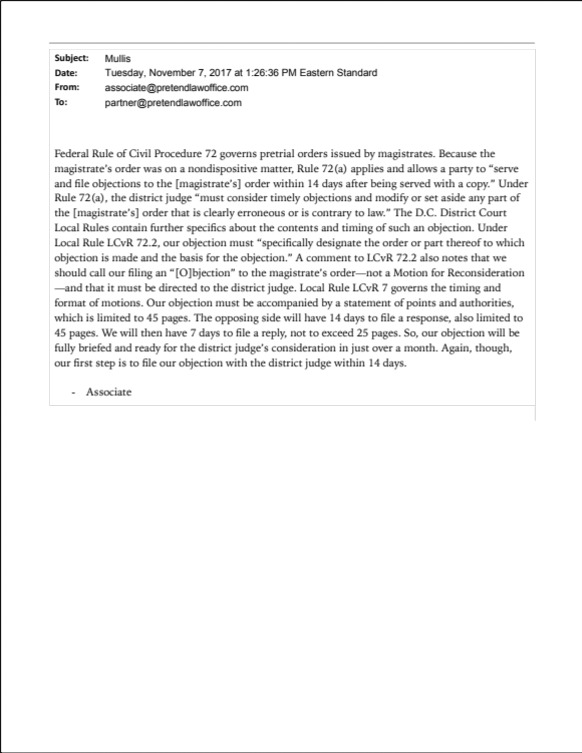

Crafting the email response. (15-20 minutes) With the answer relatively clear from our class-wide discussion, the students have the remainder of the class to craft an email response that incorporates the lessons on effective email practices. Depending on the length of class and the complexity of the issues involved, students could research and then write an email from scratch—but that has proved too much for our one-hour class sessions. So, as an alternative, students can be given a substantively correct but poorly organized/formatted via email that the professor has drafted ahead of time.[114] That way, students can cut-and-paste the substance of the answer into a new document and then reorganize and re-format the email to make it more effective. This further reduces cognitive load by allowing students to focus—during that segment of the assignment—specifically on effective email organization and formatting rather than on the substance of the analysis.[115] Allowing students to work in groups also eases the burden of drafting an individual email for each person and allows students to learn from one another’s ideas.[116]

If time remains after students submit their emails, it can be helpful to have a short, class-wide discussion on what the students did to make their emails more effective. To the extent that there are commonalities among the groups, it drives home the importance of those elements. And if there are differences, it allows the students to discuss the merits of different approaches.[117] Providing sample or model email responses for students to review after class can allow students to self-assess their work and to improve for future email tasks.[118] But students may struggle to understand what separates the quality of their work from the quality reflected in the model.[119] So giving students multiple, annotated responses that highlight the positive aspects of the model and giving students the chance to review the model answers in groups can maximize the chances that students can learn from model answers.[120] And a checklist or grading rubric can be another useful tool—either for the professor to effectively and efficiently assess student learning outcomes or for students to self-assess their own learning.[121]

Timing. In terms of timing, I have chosen to do the assignment at the end of the fall semester for two primary reasons. First, the students’ experience in writing a full, complex memo assignment provides a relevant reference point for showing the differences between the structure and complexity of a traditional, formal memo and the more limited analysis of the procedurally focused e-memo.[122] Second, some students will be emailing with potential summer employers or doing short internships over winter break, and the exercise allows them to practice effective and professional email skills right before applying them in a real-world setting. But this assignment could also be done at the beginning of the semester as a way to introduce the concept of legal rules without the added complication of fact-based application.[123]

Reflections. Generally, students have reacted positively to the assignment and have produced high-quality responses. As mentioned above, asking students to draft an entire email response from scratch was simply too onerous for a single, one-hour class session, and many students expressed that they felt rushed to complete the assignment. The following year, this problem was largely solved by giving students a substantively correct, but poorly formatted email and asking them to edit it to be more effective. This proved far more manageable in a single class period and resulted in higher-quality email responses. Indeed, I have been extremely impressed with the quality of the email responses, which are clear, concise, and largely satisfy the learning outcomes surrounding organization, formatting, and tone. And the assignment has produced one helpful spillover benefit: focusing so explicitly on email formatting and organization has made me much more cognizant of my email practices when communicating with students. I am much more careful when crafting emails to individual students and class-wide announcements in an effort to ensure that I am modeling the same best practices that I teach.

CONCLUSION

Now that there is broad recognition of the importance of teaching email in the first-year curriculum, legal writing faculty must consider what types of email assignments they are using and the pedagogical goals that those assignments serve. Summary E-memo assignments are valuable additions to the curriculum, but relying solely on them misses opportunities to help students build additional skills they will need as attorneys. Standalone E-memo assignments—and in particular, the Procedural E-memo assignment described in this Article—offer efficient ways for students to build important skills in practical online research and in writing the clear, focused, time-sensitive emails that are so prevalent in today’s practice. I hope that this Article will inspire other legal writing faculty to think creatively about expanding the use of email assignments in their courses to better prepare students for the modern practice they are about to enter.

For example, a 2015 survey conducted by LexisNexis found that “95% of hiring partners and senior associates who supervise new attorneys” believe that “recently graduated students lack key practical skills at the time of hiring.” LexisNexis, Hiring Partners Reveal New Attorney Readiness for Real World Practice (2015), https://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20150325064926_large.pdf.

See, e.g., Ellie Margolis & Kristen Murray, Using Information Theory Literacy to Prepare Practice-Ready Graduates, 39 U. Haw. L. Rev. 1, 17 (2016) (“The call to produce “practice-ready” graduates has become an increasingly prevalent part of the discussion on legal education.”); Ann Sinsheimer & David J. Herring, Lawyers at Work: A Study of the Reading, Writing, and Communication Practices of Legal Professionals, 21 Leg. Writing 63, 65 (2016) (“[T]he rising costs of legal education and an increasingly competitive legal employment market have put additional pressure upon law schools to do more to prepare their students for legal practice.”); Sheila F. Miller, Are We Teaching What They Will Use? Surveying Alumni to Assess Whether Skills Teaching Aligns with Alumni Practice, 32 Miss. C.L. Rev. 419, 421 (2014) (suggesting that legal writing faculty “develop strategies to ensure the teaching is relevant to the current practice of law”).

Kendra H. Fershee, The New Legal Writing: The Importance of Teaching Law Students How to Use E-mail Professionally, 71 Md. L. Rev. Endnotes 1, 1 (2011); see also Linda H. Edwards, Legal Writing and Analysis 147 (4th ed. 2015).

See Helene S. Shapo, Marilyn Walter & Elizabeth Fajans, Writing and Analysis in the Law 182 (6th ed. 2013) (“[Emails] are less expensive in terms of billing time and they accommodate the recipient’s need for a fast response.”); Kirsten K. Davis, “The Reports of My Death Are Greatly Exaggerated”: Reading and Writing Objective Legal Memoranda in a Mobile Computing Age, 92 Or. L. Rev. 471, 473 (2013) (“In today’s legal practice culture of on-screen reading and writing, lawyers complain memos are expensive, time consuming, and perhaps even ill-suited for reading on screens and mobile devices.”); Fershee, supra note 3, at 2 (“The reasons for the newly emerging preference for e-mail are multilayered and driven by client demands for cost-savings and efficiency . . . .”).

By “traditional, formal memorandum,” I largely adopt Kristen Tiscione’s definition: “a formal written memorandum that used to be sent through the mail to clients, usually containing a prescribed number and order of elements: a question presented or issue, brief answer or summary of analysis, statement of facts, discussion or analysis, and conclusion.” Kristen K. Robbins-Tiscione, From Snail Mail to E-Mail: The Traditional Legal Memorandum in the Twenty-First Century, 58 J. Legal Educ. 32, 32 n.1 (2008). For purposes of this Article, when distinguishing between “traditional, formal memoranda,” and e-memos, I focus on the formality of the presentation—the prescribed form or the number of traditional sections—not on the method of delivery. In other words, I see no difference between a “traditional, formal memorandum” delivered to the reader in paper form and the same document delivered in electronic form—for example, by emailing a PDF document.

See Kristen K. Tiscione, The Rhetoric of E-mail in Law Practice, 92 Or. L. Rev. 525, 540 (2013) (noting that email has “for the most part . . . become the best way to fulfill the attorney’s ethical duties, meet client demands, and stay in practice”); Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5, at 32–33 (noting that, according to a survey of practicing attorneys, “substantive e-mail ranks first as the graduates’ method of choice for communicating with clients”).

Katrina June Lee, Process over Product: A Pedagogical Focus on Email as a Means of Refining Legal Analysis, 44 Cap. U. L. Rev. 655, 664 (2016).

See infra notes 9–24. This Article focuses on teaching email skills in first-year legal writing courses, as opposed to upper-level legal writing courses or doctrinal courses. This is largely because the bulk of scholarship on email pedagogy has been in the context of first-year legal writing courses, and this Article is, in part, a response to that prior scholarship. Because first-year legal writing courses are already loaded with content, it may be possible that the some of the ideas and assignments discussed in this Article would fit more comfortably in upper-level courses. This Article’s broader point is that students should be exposed to a range of email assignments at some point in the curriculum—whether in the first-year legal writing course or at some other point.

One example is a 2016 article by Katrina Lee, which discussed the pedagogical benefits and rationales for using email assignments in the middle of larger memo-writing project to help students develop better legal reasoning abilities. See Lee, supra note 7; infra notes 51–52 and accompanying text.

ABA Section of Legal Education & Admission to the Bar, Managing Directors Guidance Memo: Standards 301, 302, 314, and 315, at 3 (2015), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/governancedocuments/2015_learning_outcomes_guidance.authcheckdam.pdf (advocating for a focus on student learning outcomes as a way of ensuring that law schools are “intentional about curriculum development”).

See infra notes 13–19 and accompanying text.

See infra notes 23–31 and accompanying text.

See Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5, at 32.

See Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 2; Miller, supra note 2; Susan C. Wawrose, What Do Legal Employers Want to See in New Graduates?: Using Focus Groups to Find Out, 39 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 505, 538–39 (2013).

Kristen Tiscione’s 2006 survey of Georgetown Law alumni was skewed toward large-firm attorneys, with nearly half (43.6%) of respondents practicing in firms with more than 200 attorneys, and just a quarter (26.4%) in firms with fewer than 25 attorneys. See Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5, at 52. But subsequent studies have been more diverse in terms of the types of attorneys surveyed and the size of offices in which they worked. For example, more than half (52%) of the respondents in Sheila Miller’s survey of University of Dayton School of Law alumni worked in offices with fewer than 10 attorneys; more than one-third (38%) worked in government or in-house legal offices. Miller, supra note 2, at 425–26. And the nineteen participants in Susan Wawrose’s focus groups were similarly diverse, comprising lawyers in the Dayton, Ohio area from large, mid-sized, and small firms, in-house counsel, a public defender, and a legal aid attorney. Wawrose, supra note 14, at 515–16. Most recently, the 2016 ethnographic study conducted by Ann Sinsheimer and David Herring followed associates at large and medium-size Pittsburgh area law firms, a solo practice, and a nonprofit agency. See Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 2, at 70.

Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 2, at 78.

Id. at 99 (“In contrast to what is taught in the traditional first-year legal writing class, these associates [that were observed during an ethnographic study] wrote few formal legal memoranda. Instead, they more often summarized research findings in informal email communications to supervising attorneys.”); Ass’n of Legal Writing Directors & Legal Writing Inst., Report of the Annual Legal Writing Survey 2015, at xi, http://www.alwd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/2015-survey.pdf (noting that “the office memorandum has always been the writing assignment used most by writing programs” that in the 2014–2015 school year, 100% of legal writing programs reported using an office memorandum assignment).

Ellie Margolis, Is the Medium the Message?, 12 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric: JALWD 1, 9 (2015) (emphasis added).

See Kristen J. Hazelwood, Technology and Client Communications: Preparing Law Students and New Lawyers to Make Choices that Comply with the Ethical Duties of Confidentiality, Competence, and Communication, 83 Miss. L.J. 245, 285–86 (2014) (arguing that email-based assignments are “crucial to a well-rounded legal writing curriculum”) (emphasis added).

Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5, at 32.

Katie Rose Guest Pryal, The Genre Discovery Approach: Preparing Law Students to Write Any Legal Document, 59 Wayne L. Rev. 351, 368–69 (2013).

Ellie Margolis, Incorporating Electronic Communication in the LRW Classroom, 19 Persps: Teaching Legal Res. & Writing 121, 121 (2011).

See Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5; Margolis, supra note 18; see also Alexa Z. Chew & Katie Rose Guest Pryal, The Complete Legal Writer 133 (2016).

See Tiscione, supra note 6; Margolis, supra note 18.

See Tiscione, supra note 6, at 532–33; Margolis, supra note 18, at 8–9.

See Tiscione, supra note 6, at 530–31; Margolis, supra note 18, at 9–10.

See Tiscione, supra note 6, at 543.

Davis, supra note 4, at 486.

Id. at 508.

Id. at 487 (“By engaging in the summarizing, short-form writing that lawyers (or their clients) apparently want in reading e-mail or informal memos, writers run the risk of giving readers what they should not want—poorly thought-through legal analysis.”).

Id. at 486.

Lee, supra note 7, at 655; see also Tiscione, supra note 6, at 525 (“[M]any legal writing professors have incorporated professional e-mail into their first-year courses.”).

Ass’n of Legal Writing Directors & Legal Writing Inst., Report of the Annual Legal Writing Survey 2015, at xi, 13, http://www.alwd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/2015-survey.pdf; Ass’n of Legal Writing Directors & Legal Writing Inst., Report of the Annual Legal Writing Survey 2012, at 13, http://www.alwd.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/2012-survey-results.pdf.

Cf. Davis, supra note 4, at 487 (“[A] memo, whether electronic, formal, informal, or streamlined, should use the number of words and paragraphs necessary to convey a solid, well-thought-out legal analysis.”).

To the extent this Article relies on a survey of published accounts of email assignments, it may, obviously, miss other, unreported ways that email has been incorporated into the curriculum. But the published articles in this area—over a long period of time and across schools and publications—appear to have a high degree of overlap on the types of email assignments that have been used, suggesting that it is representative of the types of assignments that are most common in first-year writing programs.

See Margolis, supra note 18, at 124 (describing an assignment assigned in conjunction with the students’ final memorandum of the semester, requiring students “to attach to their memos an e-mail summary of their analysis”); Kirsten A. Dauphinais, Using an Interviewing, Counseling, Negotiating, and Drafting Simulation in the First Year Legal Writing Program, 15 Transactions: Tenn. J. Bus. L. 105, 121 (2013) (“In some years, we have promoted yet another of the practical aspect of legal communication in requiring the students to condense the client letter’s legal advice into an email.”); Fershee, supra note 3, at 18 (“An easy way to assign practice to students is to ask them to condense an assignment already completed in the more traditional format, such as a client letter, into a shorter, more concise, clear e-mail and send it to you.”); Miller, supra note 2, at 443–44 (“A good assignment might be to ask students to take their formal memo and use it as the basis for an e-mail to a client . . . .”); Charles Calleros, Traditional Office Memoranda and E-mail Memos, in Practice and in the First Semester, 21 Persps.: Teaching Legal Res. & Writing 105, 108 (2013) (describing one possible email assignment as “a client advice letter summarizing analysis from a traditional office memo”). Alyssa Dragnich describes another variation of this type of assignment, where students—after briefing a trial motion—have to email their client to report how the presiding judge has ruled on the motion. Alyssa Dragnich, Teaching Ethics Through a Client Email Communication Assignment, 26 The Second Draft, Fall 2012, at 14, 14.

See Lee, supra note 7, at 669 (“I often assign email writing in the midst of my students’ work on the longest legal writing project of the semester.”).

Margolis, supra note 18, at 123.

See, e.g., Ralph L Brill, et al., Sourcebook on Legal Writing Programs 16 (1997) (describing that learning how to “read a series of cases and extract from them their common doctrine and policy” are “part of any first-year [legal writing] course”); Amy Vorenberg & Margaret Sova McCabe, Practice Writing: Responding to the Needs of the Bench and Bar in First-Year Writing Programs, 2 Phoenix L. Rev. 1, 6 (2009).

See, e.g., William M. Sullivan, et al., Educating Lawyers: Preparation for the Profession of Law 107 (2007) (noting that in many schools’ first-year legal writing courses, “[s]tudents use simulated files of materials in order to develop full-blown legal memoranda that require students to relate a specific set of facts and procedures to a dispute at the trial level”); Vorenberg & McCabe, supra note 40, at 6–7.

Tiscione, supra note 6, at 541–42.

Miller, supra note 2, at 442.

See Vorenberg & McCabe, supra note 40, at 24.

Calleros, supra note 37, at 108 (emphasis added); see also Christine Coughlin, Joan Malmud Rocklin & Sandy Patrick, A Lawyer Writes: A Practical Guide to Legal Analysis 297 (2d ed. 2013) (providing example of simple e-memo straightforwardly describing statutory requirements for witnesses to a valid will); Wawrose, supra note 14, at 549 (describing how the author implemented a series of “three-hour’ research and response problems” in the second-semester of her legal writing course in response to focus groups with practicing attorneys).

Cf. Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 2, at 123 (recommending, based on three-year observational study of law-firm associates, that “[l]egal educators should consider developing exercises that require students to compose emails in various contexts”); Wawrose, supra note 14, at 547 (“One of the major structural changes to the first-year LRW syllabus our research suggests is the inclusion of short research and writing assignments to supplement the traditional memo and brief assignments often used in first-year LRW classes.”).

See Wawrose, supra note 14, at 541 (reporting that when focus group participants were “asked to make suggestions for the first-year legal writing curriculum, all agreed it would be better to have several short assignments in first-year legal writing class, rather than one or two lengthier memos and briefs”); Miller, supra note 2, at 444 (“One of the most consistent comments from both the follow-up interviews and the open-ended questions was to have more and shorter assignments in the first year research and writing class.”).

See Margolis, supra note 22, at 123 (noting “the challenge of working [an email] assignment into the curriculum of my fall semester LRW class, which already packs in more work than the two credits allotted to the course”).

See Miller, supra note 2, at 444 (recommending email assignments to supplement, not replace, traditional memo assignments, because the analytical skills involved in more complex assignments are “crucial”); Davis, supra note 4, at 488–89 (arguing that the process of writing a traditional memoranda helps lawyers undertake the complex legal analysis necessary for competent representation); Calleros, supra note 37, at 106 (advocating for email assignments, while recognizing that “the traditional office memorandum has important pedagogic value and should remain as a central teaching tool”).

See, e.g., Margolis & Murray, supra note 2, at 15 (“[T]he inescapable fact is that email memos have become the predominant means of communicating analysis between lawyers.”).

See infra Section IV.A.2.

See Lee, supra note 7, at 668–70.

Id. at 665.

For example, Ellie Margolis describes how she has students do a summary e-mail assignment in place of writing brief answers, in part because she “did not want to add to the students’ workload or my own by adding in this assignment without removing anything else.” See Margolis, supra note 22, at 123.

Miller, supra note 2, at 427.

Id. at 434–35.

Id. at 437.

Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 5, at 47–48.

Calleros, supra note 37, at 106.

Cf. David L. Armond & Shawn G. Nevers, The Practitioner’s Council: Connecting Legal Research Instruction and Current Legal Research Practice, 103 Law Libr. J. 575, 578 (2011) (suggesting that “law librarians with recent practice experience” can “draw on their experience in a contemporary legal research practice setting to enhance their instruction”) (citing Nolan L. Wright, Standing at the Gates: A New Law Librarian Wonders About the Future Role of the Profession in Legal Research Education, 27 Legal Reference Services Q. 305, 332–33 (2008)).

See, e.g., Thomas Y. Allman, Local Rules, Standing Orders, and Model Protocols: Where the Rubber Meets the (E-Discovery) Road, 19 Rich. J.L. & Tech. 1, at 4–5 (2013).

See, e.g., James D. Petersen & Jennifer L. Gregor, Attorneys at Work: A Flexible Notion of Plagiarism, Law 360 (Oct. 7, 2011, 12:23 PM) (“Lawyers do a lot of copying. Why charge a client to create a document from scratch when you can draw concepts, structure, and wording from a form agreement in a book [or] a brief prepared by a colleague . . . ?”); K.K. DuVivier, Nothing New Under the Sun—Plagiarism in Practice, Colo. Law., May 2003, at 53, 53 (suggesting that because “[f]iled legal documents become public records, and traditionally have not been considered privately owned intellectual property[,] . . . a good attorney can learn by trying to emulate” other attorneys’ filings).

See Margolis, supra note 22, at 123 (recognizing that in a “real-life scenario, an associate would likely have a day, or a few hours” to draft a brief email summarizing research findings); see also Wawrose, supra note 14, at 534 (reporting comments from focus group participants: “I need answers over lunch sometimes. I mean, [I] leave court and come back at one[,] I need a memorandum in an hour.”) (alteration in original).

See Wawrose, supra note 14, at 549 (advocating for realistic assignments that allow “students to become comfortable with producing assignments requiring quick turnaround”).

See generally Tracy Turner, Flexible IRAC: A Best Practices Guide, 20 Leg. Writing 233 (2015) (evaluating the various frameworks used to teach law students to engage in complex legal analysis).

See Miller, supra note 2, at 437–38.

See Cathy Glaser et al., The Lawyer’s Craft: An Introduction to Legal Analysis, Writing, Research, and Advocacy 166 (2002) (“Because [legal] analysis is an art, not a science, some lesser degree of certainty is often appropriate.”); Teresa J. Reid Rambo & Leanne J. Pflaum, Legal Writing by Design: A Guide to Great Briefs and Memos 177–78 (2013) (suggesting that “few legal questions have easy ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers”).

See, e.g., Tiscione, supra note 6, at 532; Margolis, supra note 18, at 28.

Vorenberg & McCabe, supra note 40, at 7–8 (“Neither first-year writing programs nor legal-writing texts focus attention on how the novelty or complexity of a given issue should dictate the structure and depth of analysis. Instead, students learn to explain and synthesize the law and then apply it; they are generally not instructed on how to vary their analysis according to the complexity and nature of the issue.”).

See, e.g., Wawrose, supra note 14, at 539–40 (noting that “new attorneys need to take a position,” citing focus-group responses that “the main writing problem that we have to fix in new [attorneys] is that they . . . don’t take sides”).

See Terri L. Enns & Monte Smith, Take a (Cognitive) Load Off: Creating Space to Allow First-Year Legal Writing Students to Focus on Analytical and Writing Processes, 20 Leg. Writing 109, 111–12 (2015) (insisting that first-year legal writing students often struggle because “they cannot learn as many things as we want them to learn, all at the same time”); Terrill Pollman, The Sincerest Form of Flattery: Examples and Model-Based Learning in the Classroom, 64 J. Legal Educ. 298, 301–02 (2014) (noting that “attempting many sophisticated tasks at once can make learning slow, difficult, and laborious”).

Cognitive load could further be reduced by separating the research and writing tasks in a Standalone E-memo assignment or by giving students the substance of the email and asking them to re-format the email to be more effective. See infra note 115 and accompanying text.

For example, Competency I.B.3. of the American Association of Law Librarians’ Principles and Standards for Legal Research Competency provides that students should be able to “[i]dentif[y] appropriate resources to locate the legislative, regulatory, and judicial law produced by . . . government bodies.” Am. Ass’n L. Libr., Principles and Standards for Legal Research Competency (2013), http://www.aallnet.org/Documents/Leadership-Governance/Policies/policy-legalrescompetency.pdf [hereinafter AALL Principles].

See, e.g., AALL Principles (noting in Competency II.B.3.b. that students should “[u]nderstand[] the operation of both free and subscription search platforms to skillfully craft appropriate search queries”).

See, e.g., Michele M. Bradley, Emphasizing the “R” in LRW: Customizing Instruction for Real-World Practice, 30 The Second Draft, Fall 2017, at 3, 4–5 (discussing the widespread use of Google and other free resources as a starting point for legal research); see also Miller, supra note 2, at 432 (showing survey results of recent law school alumni that 44% of respondents “always,” “very often,” or “often” used “Google, Wikipedia or other non-law related websites” in the course of their research, while 49.6% “always,” “very often” or “often” used “[n]on-commercial law related websites,” including “court or government websites”); Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 2, at 84 (explaining that associates observed as part of ethnographic study “were conscious of the cost of commercial databases like Westlaw or Lexis and tried to use free sources whenever possible”); id. at 76 (reporting observations of associates’ use of “county websites containing property assessments” and Wikipedia to gather background information).

See, e.g., Wawrose, supra note 14, at 533 (reporting focus-group comments from a legal aid employer who “found it ‘really helpful’ when new hires bring ‘creativity’ to the table to reduce costs by using free resources”); see also Ellie Margolis, Surfin’ Safari—Why Competent Lawyers Should Research on the Web, 10 Yale J. L. & Tech. 82, 115–16 (2007) (arguing that “the standard for competence in legal research will soon” include online non-legal materials such as legal blogs and news sources, given increased numbers of judicial citations to such sources).

See Patrick Meyer, The Google Effect, Multitasking, and Lost Linearity: What We Should Do, 42 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 705, 731 (2016) (arguing that law schools “must teach students how to find and appropriately use [online] free options as part of our training”); Katrina June Lee, et al., A New Era: Integrating Today’s “Next Gen” Research Tools Ravel and Casenext in the Law School Classroom, 41 Rutgers Computer & Tech. L.J. 31, 46 (2015) (“Students and lawyers alike need to understand which sources supply official authenticated sources of law and need to corroborate what they learn through free online research.”) (citing Aliza B. Kaplan & Kathleen Darvil, Think [and Practice] Like a Lawyer: Legal Research for the New Millennials, 8 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric: JAWLD 153, 186 (2011)).

See Lee, supra note 76, at 43 (citing Sanford N. Greenberg, Legal Research Training: Preparing Students for a Rapidly Changing Research Environment, 13 Leg. Writing 214, 266 (2007)).

See Miller, supra note 2, at 441–42 (describing a research assignment where students must use free, reliable online sources, such as government agency websites).

Caroline L. Osborne, The State of Legal Research Education: A Survey of First-Year Legal Research Programs, or “Why Johnny and Jane Cannot Research,” 108 Law Libr. J. 403, 409 (2016).

See supra Section III.B.3.

See Meyer, supra note 76, at 732 (encouraging law schools to train students to use “reliable free Internet sources,” such as Findlaw, Cornell’s Legal Information Institute website, and “the plethora of free government websites that host primary law”).

See, e.g., Search for FDA Guidance Documents, .U.S. Food & Drug Administration, (last updated Oct. 25, 2017), https://www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/guidances/.

See, e.g., Charlottesville, Virginia – Code of Ordinances, .Municode (last updated Aug. 11, 2017), https://library.municode.com/va/charlottesville/codes/code_of_ordinances.

USPTO Patent Full-Text and Image Database, .United States Patent and Trademark Office, http://patft.uspto.gov/netahtml/PTO/search-bool.html (last visited Nov. 6, 2017).

Executive Orders Disposition Tables Index, .National Archives (last reviewed Aug. 18, 2017), https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/executive-orders/disposition.

See Carl Tobias, Local Federal Civil Procedure for the Twenty-First Century, 77 Notre Dame L. Rev. 533, 533 (2002) (noting that “[l]awyers and parties face, and federal judges apply, a bewildering panorama of requirements,” including “[a] stunning array of local measures—including local rules; general, special, and scheduling orders; [and] individual-judge practices”).

See Meyer, supra note 77, at 732 (encouraging legal skills faculty to help “students become familiar with the layout of [free online legal] sites” and “how to properly use their search features”).

See Chew & Pryal, supra note 23, at 133 (noting that e-mail memos come “new conventions and new audience expectations”).

Edwards, supra note 3, at 160 (suggesting that subject line should “state the email’s subject and purpose in terms that will be specific enough to communicate well but not too detailed to be read at a quick glance”); Chew & Pryal, supra note 23, at 136 (urging use of “short yet informative” subject lines and suggesting that “eight words is approximately the maximum number of words that most smartphone email clients can show on their screens”); Shapo, supra note 4, at 343 (recommending “treating your subject line as a brief summary of the message”).

See Coughlin, supra note 45, at 299 (encouraging writers to name attached documents “in a way that is easy to save and find again later”).

Cf. Mary Beth Beazley, Writing (and Reading) Appellate Briefs in the Digital Age, 15 J. App. Prac. & Process 47, 63 (2014) (explaining the importance of using key words in digital documents).

See Edwards, supra note 3, at 160 (“Your reader is expecting to see the email’s point within the first two or three sentences.”); Coughlin, supra note 45, at 298 (urging legal writers to “state your bottom line up front” in emails); Shapo, supra note 4, at 343 (encouraging use of summary that “concisely states the gist and point of the e-mail”); Margolis, supra note 18, at 123; Wayne Schiess, E-Mail Like A Lawyer, 89 Mich. B.J. 48, 50 (2010) (“If you’re not asking a question but making a point, use the first sentences of the e-mail message to summarize your point.”).

Edwards, supra note 3, at 47 (“Often the email will end with some reference to the next appropriate steps.”); Tiscione, supra note 6, at 537 (“The interactive nature of e-mail makes it natural for the writer to suggest at the outset the next steps needed to strengthen her analysis.”).

See Edwards, supra note 3, at 160 (“Usually an email shouldn’t be longer than one screen on a traditional computer monitor.”); Coughlin, supra note 45, at 298 (suggesting that “the optimal length for an e-mail is one screen” due to the lack of landmarks on rolling digital screens); Shapo, supra note 4, at 343.

See Calleros, supra note 37, at 105 (suggesting that e-memos be “no more than one or two single-spaced pages so that a recipient on the move can read it without difficulty by scrolling down the screen of a compact hand-held electronic device such as a BlackBerry® or iPhone”).

Margolis, supra note 18, at 21–22 (“From the lawyer’s perspective, including hyperlinks can be a way of establishing credibility, sending the implicit message . . . that the source has been used correctly and accurately . . . .”).

See, e.g., Margolis, supra note 18; Ruth Anne Robbins, Painting with Print: Incorporating Concepts of Typographic and Layout Design into the Text of Legal Writing Documents, 2 J. Ass’n Legal Writing Directors 108 (2004); see also Matthew Butterick, Typography for Lawyers (2d ed. 2015).

Mary Beth Beazley, Writing for a Mind at Work: Appellate Advocacy and the Science of Digital Reading, 54 Duq. L. Rev. 415, 429 (2016) (“Some scientists hypothesize that digital devices impose more of a burden on our cognitive load simply due to the need to pay attention to the many functions of those devices.”).

See, e.g, Margolis, supra note 18, at 18 (reporting results of 2013 ABA survey, showing that “89% of lawyers responding use mobile devices to check their email”).

See id. at 18 (suggesting that “more-frequent headings, use of lists and bullet points, and using white space and text proximity” can create “substantive and visual cues about organization”); Tiscione, supra note 6, at 532–33 (noting that emails using “visual cues or markers such as lists, bullets, or headings to highlight parts of the text . . . are arguably more effective”); Davis, supra note 4, at 521 (“Certainly, memos conveyed in the body of an e-mail, for example, would benefit greatly from the generous use of headings.”).

Davis, supra note 4, at 521 (recommending that digital writers use “well-constructed, concise paragraphs to aid the reader who might be using a small screen”).

Beazley, supra note 99, at 444; Margolis, supra note 18, at 17.

See Beazley, supra note 99, at 444 (suggesting use of bolding for headings in digital documents); Davis, supra note 4, at 521 (2013) (noting that all writers writing in digital formats “should pay extra attention to the use of boldface type and bullet points for emphasis of important points, to text structure signals that show the relationship between ideas”).

Hazelwood, supra note 19, at 282 (citing Fershee, supra note 3, at 12–14).

See, e.g., Edwards, supra note 3, at 161–62.

Id. at 161 (“Emails usually should be slightly less formal than traditional professional writing but more formal than a social message.”); Chew & Pryal, supra note 22, at 136 (“[T]he the persona you present in your memo can and should be less formal than the persona you present in other legal documents.”); Robbins-Tiscione, supra note 4, at 44 (“Although e-mail is by nature informal, students should not perceive it as a more casual form of communication than a memo to another attorney.”) (internal quotation marks omitted); see also Sinsheimer & Herring, supra note 1, at 73 (noting, based on observations of law-firm associates, that “their composing process for email exhibited meticulousness and a high degree of concern for word choice and tone”).

See Edwards, supra note 3, at 161 (suggesting that contractions in emails “often make the message easier to read” and that omitting contractions “can make the message seem stilted, awkward, and arrogant”).

Id. (noting that in emails, a first name or last name can be used “according to the situation”).

See Hazelwood, supra note 19, at 286–89 (listing a number of ethical issues surrounding email that legal writing courses could raise, including third-party access/interception, metadata, data retention, and inadvertent disclosure); Dragnich, supra note 36 at 15 (discussing how an email assignment could include lessons about confidentiality, attorney-client privilege, and “contemporary issues such as information security and removal of metadata prior to transmitting documents”); Tracy Turner, E-mail Etiquette in the Business World, 18 No. 1 Persps.: Teaching Legal Research & Writing 18, 19–20 (2009) (discussing ethical and professional email issues, including when to use email versus other forms of communication, forwards and replies, and CC and BCC use); see also Shapo, supra note 3, at 345 (“If you are forwarding a message to another attorney, for example, check that there is nothing in the thread that is not for the eyes of that recipient. In fact, if the thread does not contain information that the recipient needs, delete the thread.”).

See infra, Appendix A: Rule 72 Email Prompt; cf. Lee, supra note 7, at 669 (describing an email assignment where students receive the prompt from a fictitious partner by way of a transcription of a realistic voicemail message).

See supra notes 87–88 and accompanying text.

See Fed. R. Civ. P. 5.2; D.C. Dist. Ct. Local Civ. R. 5.4(f).

See Fed. R. Civ. P. 72(a); D.C. Dist. Ct. Local Civ. R. 72.2.

See infra Appendix B: “Bad” Rule 72 Email Response.

See Pollman, supra note 71, at 317 (“Creating a subgoal or segmenting a problem into distinct parts helps lessen cognitive load.”); id. at 307 (noting that when “writing students expend so much of their mental energy on completing an assigned document[,] they have little to no mental energy left to reflect and learn from the writing experience itself”). Still another variation would be to present students with the poorly formatted and poorly organized email and ask them to identify and discuss the shortcomings. This would further reduce cognitive load and allow students to explore what makes for an effective email without the added pressure of having to produce a tangible product. Cf. Enns & Smith, supra note 71, at 131–33 (describing an exercise where students review a poorly written memo and explain deficiencies, using a rubric).