I. INTRODUCTION: THE OBLIGATION TO TEACH GRAMMAR AND PUNCTUATION SUCCESSFULLY TO ALL STUDENTS

Students enter law school to acquire the specialized knowledge and skills necessary for legal practice.[1] Their likelihood of success in the legal academy is subject to many measures: LSAT, GPA, and undergraduate institution and major. However, for a variety of reasons, students often enter law school without necessary fundamental skills to thrive. One such skill is the ability to write using standard, correct grammar and punctuation.[2] Content apart, correct writing is a gatekeeper in the legal profession, critical for attorneys[3] and their clients.[4] Further, lack of knowledge of the rules governing standard or professional writing can serve as a proxy for other deficits in students’ previous instruction.

Many law schools have responded to the perceived lack of skills in entering and continuing law students with programs and courses targeted at writing and academic success in general.[5] However, to date, little quantitative data have been gathered and analyzed about entering law students’ grammar and punctuation skills or about satisfactory programs to address the instructional needs students may have. This leaves a gap in the discussion both of student needs and effective institutional responses. This Article discusses the writing seminar program at Michigan State University College of Law, which forms part of the first-year curriculum in legal writing and provides instruction in grammar and punctuation. We analyze our program and its success through quantitative data collected over five years from five cohorts of first-year students.

Our program is modeled on the writing specialist/writing seminar model pioneered at Seattle University School of Law by Professor Anne Enquist, who was gracious enough to consult with the MSU writing program and faculty.[6] Central to the Seattle program and our own is optional instruction—delivered through lectures, workshops, and office hours—full integration with the first- and second-semester legal writing courses, and mandatory assessment. Assessment in the writing skills program at MSU is based on students demonstrating proficiency, not ranking with a forced curve, and is otherwise ungraded. Students are required to demonstrate proficiency before exiting the program rather than exiting at defined time regardless of skill level.

We collected data regarding students’ entering skills in grammar and punctuation, their attendance at optional writing seminars and office hours, their attainment of proficiency and actual score on the final assessment, and, where possible, cumulative law school GPA and bar results. Using these data, the study sought to answer the following questions:

-

Could a voluntary program that frames fundamental writing skills as professional development rather than remediation and is run on a proficiency model successfully engage students, particularly students most in need of instruction?

-

Did students who used optional program resources demonstrate increased skill with the material and greater improvement than students who did not use the optional resources?

-

Does student performance on an assessment designed to measure skill with grammar and punctuation predict or correlate with other outcomes of legal education, such as cumulative law school GPA or first-time bar passage?

Data indicate that the vast majority of students during the five-year study period voluntarily attended the writing seminars and attained proficiency by the end of the fall semester. The high level of attendance and early acquisition of proficiency testify to the potency of intrinsic student motivation when actions and outcomes are clearly identified and align with students’ aspirations for future professionalism, not remediation of past inadequacy. The data indicate that such quantitative studies, coupled with qualitative comments by students and faculty, are worthwhile measures of the contribution of programs like ours to students’ success. Our methods provide a case study in how to use outcome data to help evaluate instructional design to enable institutions and individuals to supplement more qualitative and subjective measures, such as instructor perception or personal anecdotes.

Part II of this Article analyzes obstacles to teaching conventions of grammar and punctuation in law school. Part III discusses the values of the MSU writing seminar program, intended to lower barriers to students learning fundamental writing skills; the instructional sequence; and the assessment instruments. Part IV indicates the methods used for our study of the program’s effectiveness, including data collection and parameters. Part V provides and discusses the results of the study in terms of student engagement and success within the program. Part VI presents the correlations between internal program data—that is scores on the students’ initial assessment—and cumulative law school GPA and their later performance in bar passage. Finally, part VII discusses overall implications of our study and our conclusions.

II. OBSTACLES TO TEACHING FUNDAMENTAL SKILLS SUCH AS GRAMMAR AND PUNCTUATION

There are several practical obstacles to teaching grammar and punctuation in law colleges. As Alaka’s 2010 article points out, faculty members both inside and outside the legal academy, as products of contemporary education, may feel relatively ill at ease teaching this material.[7] Time is limited in any course, and coverage requirements may discourage teaching writing skills. Teaching skills is demanding, time consuming, and relatively expensive within the context of the first-year curriculum. Yet the discussion surrounding grammar and punctuation frequently moves beyond these concerns to a more value-laden rhetoric than might be expected for an effort to impart a set of writing conventions that, as we will show, are fairly easily grasped by most students. This attitude is more striking because the cost for students and future clients for lack of skill in the areas of writing and editing is readily acknowledged to be high.

The debate over writing and particularly writing mechanics is shaped by the traditional dichotomy between reasoning/meaning and expression/ornamentation in which the first set of terms is considered fundamental and controlling while the second is derivative, subordinate, and less valuable.[8] Thus, for example, the LSAT identifies the goal of the scored portions of the test as measuring skills considered “essential for success in law school: the reading and comprehension of complex texts with accuracy and insight; the organization and management of information and the ability to draw reasonable inferences from it; the ability to think critically; and the analysis and evaluation of the reasoning and arguments of others.”[9] The purpose of the writing sample, on the other hand, is not defined, and the sample is not assessed. While the writing sample is frequently said to play little role in admissions, students are warned, “It’s unfortunate, but misspellings and bad grammar can quickly undermine the best of arguments.”[10]

Thus, from the beginning, grammar and punctuation are readily conceptualized as inferior to or separate from reasoning and meaning.[11] Yet a long-standing association of mistakes in writing mechanics with loss of credibility, a fact often invoked to underscore the necessity of error-free expression,[12] increases the perceived significance of such errors for both professors and students. The close linkage of credibility and virtue in our rhetorical tradition, which historically and currently associates credibility with the sincerity and moral worth of the speaker, ties errors in credibility to errors in character.[13] Students enter a world in which poor writing mechanics—often a result of inadequate instruction, that is, of institutional failure—are reconceptualized as, or conflated with, students’ personal deficiencies.[14] Thus, faculty can be reluctant to teach writing mechanics on the grounds that students “should” normatively already know these rules.[15] Not surprisingly, students are correspondingly reluctant to accept instruction if “remedial” education is tied to personal deficits on the part of persons who are to be remediated.[16]

However, lack of teaching and of learning in this area perpetuates a traditional role for diction and grammar, including writing mechanics: maintenance of social capital and reinforcement of hierarchy. Looking for deviation from elite norms in writing and speaking is a handy way to eliminate, for example, job applicants. Poor grammar and punctuation readily become class markers in a hiring situation in which social class already plays an identifiable role, particularly at elite firms.[17] Thus, the failure to teach grammar and punctuation exacerbates the perception that law school is a sorting mechanism, and may allow sorting on social grounds.

III. VALUES, INSTRUCTIONAL SEQUENCE, AND ASSESSMENT IN THE MSU WRITING SEMINAR PROGRAM

A. Defining Values

1. Reconceptualizing Instruction in Grammar and Punctuation to Remove Potential Stigma

Students are often deterred from seeking instruction when instruction is conceptualized as remedial or indicative of lack of ability.[18] This aversion to seeking help is amplified by students’ previous success with writing as undergraduates, which allows students to believe that their current skills will suffice for the new challenges of writing in law school. To overcome this barrier, we re-framed the discussion surrounding writing mechanics to focus on the transition from discipline-specific undergraduate writing conventions to the conventions employed in the legal academy and legal profession.[19] We cultivate the idea that all students, not just low-performing students, need instruction in what is fundamentally a new discourse.[20] This approach builds on research on undergraduate writers indicating that students who self-identify as “experts” in the conventions of writing from previous experience show less improvement as writers over the long term than students who self-identify as “novices”[21] and that students who are aware that conventions, standards, and techniques differ based on context hold a strategic advantage over their peers who lack such an understanding.[22] This approach harmonizes with the rhetoric of the first year of law school as one in which students are initiated into a new way of thinking with different rules and vocabulary.[23] Our approach invokes students’ professional aspirations for the future rather than orienting them to an inadequate past.[24] Grammatical and stylistic choices—for example, the legal preference for serial commas and maintenance of the “that”/“which” distinction—are presented in the MSU Law program as discipline-specific skills that contribute to the students’ acquisition of a new professional identity[25] and branding as attorneys.[26] Explanation of the role of rules of punctuation and grammar in enhancing clarity and in litigation allows students to incorporate what they are learning into the overall project of the first year, instead of to experience instruction as filling gaps and correcting past failures or as mitigating problems derived from socio-linguistic provenance.[27]

2. Adoption of an Assessment and Proficiency Approach, Rather Than Evaluation and Ranking

The instructional sequence and assessments are discussed in detail in the next sections (B and C), but, in short, all students take an initial required formative assessment covering grammar and punctuation conventions.[28] Students are provided with a recommended course of study based on their initial score, offered a variety of instructional opportunities, and required to pass a post-test demonstrating proficiency. The score necessary to pass the Proficiency Test is clearly advertised at writing seminars and announced in legal writing classes. Students’ grades in second semester legal writing would not be released until proficiency was demonstrated on one of the Proficiency Tests.

One of the goals of legal education is to develop self-motivated students who have the intellectual and personal characteristics to continue to master new material and meet new challenges throughout their careers.[29] Yet this professionally and personally desirable outcome may be incompatible with the extrinsic motivators of law school, for example forced curves and high-stakes testing.[30] Further, the evaluate-and-move-on approach of most law school courses, with its final goal of sorting and ranking students[31] (and removing those who do not make the grade), does not effectively facilitate students’ acquisition of the fundamental skills they will need to serve their eventual clients.[32] Finally, research on student help seeking points to the importance of a context of mastery goals, as opposed to comparison-based ability goals, to prompt students to seek out instruction when it is needed.[33]

For our program, student motivation was vital because student participation in the instruction offered in the writing seminar program was explicitly designed as voluntary. Further, our program abandoned the traditional zero-sum, competitive ranking of law school courses and focused instead on a what we call a proficiency model, emphasizing that all students could achieve proficiency over time.[34] The positive incentives for high levels of student engagement in the writing seminar program invoke the students’ desire to join a professional community and assuage their anxiety about doing so. The material in the writing seminars is presented as essential for attorneys and common to the professional community. Thus, students are motivated to learn because it explicitly links to the goals of socialization and formation of professional identity that students and faculty alike see as central to the first year of law school.[35] Further, the proficiency model calms students and allows them to anticipate success during the stressful 1L year because it both requires and allows all students to succeed at some point during their first year, something not true of their other courses. Thus, students are emotionally drawn to and invested in the writing seminar process. Allowing students to choose what instructional resources to access and even when to take the Proficiency Test (some students explicitly postpone it until the second semester) honors students’ independence, puts them in charge of their own education, and contributes to their emerging view of themselves as professionals who must manage competing priorities.

A proficiency model is distinct from a pass/fail model. While a pass/fail model does eliminate internal ranking, it remains a ranking system to the extent that students are not required to learn the material, but simply to be evaluated on whether they did learn it or not. In many instances, failure has no repercussions beyond notation on a transcript and does not require students to continue learning. Proficiency is both a more demanding standard than passing—we set the bar at 75% correct answers, which would traditionally correlate with a “C,” while institutions may define lower scores as “passing”—and, more importantly, a requirement for exit: no student leaves our program until the student meets or exceeds the 75% requirement. Students and professors continue to work until proficiency is achieved. This is appropriately called a proficiency approach because the goal of instruction, understood by students and professors alike, is becoming proficient with specific content, not evaluation. A proficiency approach is the appropriate model for fundamental skills whose benefits will be experienced by students and clients alike. This approach reflects that of the professional world that students aspire to enter and is most characteristic of clinics, where, as in law practice, poor work product is met with a request that it be redone satisfactorily rather than with a low grade and nothing further.

3. Promotion of Student Autonomy Through Optional Instruction and Student Choice of Timing

Our program couples optional instruction with mandatory assessment.[36] Thus, within limits, this model relies on students to set their own priorities and goals, but we provide them with pertinent information to help guide their choices: roadmaps for success explicitly tied to assessment of their initial skills. In the design phase, we believed that tying the writing seminar program to the students’ own goals, honoring their priorities in the first semester, and amplifying intrinsic motivation would promote students’ enthusiasm and encourage participation in the program.[37] This approach dovetails with the goal of helping students achieve proficiency rather than ranking students based on their scores.

Performance in the writing seminar program had no impact on students’ grades, except to the extent that legal writing professors would also grade on correct mechanics as described in the next subsection. Students could prepare for the test in whatever way they chose: through self-study, office hours, partial engagement with the writing seminars, full attendance at the writing seminars, or any combination. Further, students were free not to engage with the writing seminar program at all during their first semester but to postpone all engagement until the spring semester.[38] The voluntary nature of the program was clearly indicated on all legal writing and program documents and explicitly discussed by all legal writing professors, who also, however, discussed the benefits of early attention to the material.

4. Integration of the Writing Seminars and the Legal Writing Program

During the study period, students understood the importance of the skills taught in the writing seminar program because the program and content were fully integrated into the legal writing courses, present on a common syllabus, and referenced often by the legal writing professors, who shared common curriculum goals and vocabulary with the seminar program.[39] The writing specialist’s name, contact information, and office hours appeared at the head of every legal writing course syllabus, below the main professor’s name. The optional seminars appeared on the legal writing syllabus and were held, whenever possible, during scheduled class time. The initial Writing Skills Inventory was returned by the legal writing professors during class, and the professors discussed its importance and the significance of the results for each student. Professors used a common “Writing Checklist” with each graded assignment. The checklist keyed students’ errors to the writing seminar and section in the writing textbook discussing the appropriate issue. In addition, legal writing professors were able to refer students to the writing specialist for individual appointments, although, in keeping with the philosophy of student autonomy, students were never required to visit the writing specialist.

Institutionally, the writing specialist, who teaches the writing seminar program, is a full-time clinical faculty member and part of the legal writing program. Further, the writing specialist attends all writing program meetings and makes regular overall and individual reports about student progress.

5. Commitment to Measuring Success, or Failure, and Primacy of Instructional Efficacy

Once the materials for the writing seminar program were finalized, we began collecting the data discussed in the results below. However, our students come first. Because no student leaves the program until proficiency is achieved—a standard no less demanding of the professor than the students—we have a particular interest in knowing what works and whether students are mastering the material at the earliest possible opportunity consistent with their own priorities. Thus, we continually use program data to improve our program in order to provide our students with the best educational experience possible. For example, the first year after the study period ended, when we realized that students would benefit by switching the order of two seminars, we made the change.

B. Instructional Sequence

The Michigan State University (MSU) program has several parts that span the first year of law school. The sequence has remained unchanged since the inception of the program and is discussed here. For more information about construction and content of the assessments, see the next subsection.

1. Writing Skills Inventory

During fall orientation, entering first-year students take the Writing Skills Inventory (WSI), our pre-instruction assessment. The assessment is in the same format and covers the same content as the Proficiency Tests, our post-instruction assessment. The WSI is a purely formative exam.[40] Students receive the results of the WSI with each error keyed to the appropriate section of the textbook for our program and the time and date of the seminar that addresses that particular skill or subject. In addition, students are given an overall score and given advice about the best strategy to pass the Proficiency Test based on their score. The information suggests several possible strategies based on the range into which students’ scores fall: “attend the Writing Seminars,” “review Just Writing and . . . exercises,” and “schedule an appointment with the Writing Specialist . . . to review the test and discuss your plan of action.”[41] After being exposed to the ways to prepare for the Proficiency Test, students are free to pick whatever approach they prefer.

2. Writing Seminars and Office Hours

After students receive the results of the WSI, they may attend any or all of five optional writing seminars taught by the writing specialist, each covering a different set of skills assessed on the WSI and Proficiency Test. In addition, the writing specialist has extensive office hours for individual conferences with students[42] and provides optional editing seminars to help students apply skills taught in the seminars to their own writing.

3. Reinforcement in the Legal Writing Classes

The integration with the first-year legal writing course means that skills taught in the writing seminars and covered in the recommended sections of the textbook are reinforced in first- and second-semester legal writing.

4. Final Proficiency Test

At the end of the fall semester, students take a Proficiency Test (PT). The PT is structured identically to the WSI and covers the same content. However, the PT is written in professional legal English and uses legal content and examples. Students must score at least 75% (24/32) on the PT to receive the grade in their second semester legal writing course. Otherwise, the score on the PT has no impact on students’ grades. Once a student has demonstrated proficiency, his or her obligations in the writing seminar program end. However, students are free to continue to consult with the writing specialist, and many do.

5. Additional Instruction for Non-Proficient Students

Collection of assessment data for this study ended after the first PT. However, within the program, first-year students who do not demonstrate proficiency on the fall PT take a second PT offered in February of their first year. The writing specialist consults individually with each student about how to prepare for the second test. Students can join small study groups facilitated by the writing specialist, work independently with support from the writing specialist, or study entirely on their own. Students who do not achieve proficiency on the second PT are highly encouraged to enroll in a “boot camp” led by the writing specialist.[43] After several weeks of intensive review and study with the writing specialist, or whatever preparation they determine is in their best interest, these students take a third PT. During the study period, no first-year student has ever had a grade held due to failure to pass a PT.[44]

C. Creation and Content of the Assessments

1. Creation of Assessments

All assessments used in the MSU Law Writing Seminar program were developed in-house by two of the Authors of this Article, Daphne O’Regan, co-director of the legal writing program, and Jeremy Francis, the writing specialist. Each assessment took dozens (if not hundreds) of work hours to complete, test, pilot, validate, and revise. Our operating assumption has always been that our assessments must reflect the pedagogical values guiding the writing seminar program, not be merely a tool for evaluation. They are criteria referenced, not norm referenced, as students’ performance is weighed not against other students, but against the standard of proficiency, which we expect all students to attain.[45]

2. Content of Assessments

We teach and assess only skills we consider essential to clear communication: sentence fragments and run on sentences; commas, including restrictive and nonrestrictive clauses; semicolons; apostrophes; tense; pronoun and verb agreement; passive voice; and parallel structure.[46]

3. Format of Assessments

Both the WSI and PT have 32 multiple-choice questions with 5 possible answers, listed A–E. The questions are divided into three sections. One section tests students’ ability to read and edit an extended writing sample via multiple-choice questions that allow the students to edit sentences in various ways or identify them as “Correct as written.” A second section provides short scenarios followed by sentences describing the scenario and asks the students to choose which sentence best describes the scenario using correct grammar or punctuation. A third section provides a number of sentences and asks students to choose which sentence or group of sentences uses correct grammar and punctuation.[47]

Multiple-choice testing is well suited for rule-based content such as grammar and punctuation.[48] It allows us to assess all students on the same content. This common, objective assessment would be difficult with student-generated writing samples because students could avoid areas of weakness and discomfort, could limit the length of responses to provide less data, and could fail, therefore, to address all areas we wish to assess.[49] In addition, multiple-choice tests allow assessment of proofreading skills and of correct choices among various punctuation options to convey particular meanings. Further, clearly defined wrong answers provide additional data for professors, students, and researchers about potential sources of student confusion. However, the tests do have shortcomings. First, they only indirectly test students’ positive ability to craft content by choosing among a variety of grammatical tools and punctuation. Second, in common with all multiple-choice tests, the tests may privilege students whose real skill is simply taking multiple-choice tests or who have greater visual acuity or attention to detail.[50] We have attempted to reduce the impact of such differences between students and the impact of reading speed, which is not something we are testing, by making the tests essentially untimed as discussed below.

To minimize the potential impact of differing assessments on student outcomes, we have either reused identical tests or established the equivalency of versions of the test. We use the same WSI every year because the inventory is informative only and students have only recently arrived at the law college when it is administered. However, we rotate three PTs to make sure that student outcomes are not influenced by familiarity with the test or by information from other students. The tests assess the same skills in exactly the same way, but in a different order and with different text. The equivalence of the tests has been demonstrated by an overwhelming consistency from year to year. For example, from 2009 to 2012, the same number of students did not pass the first test, roughly forty out of each cohort of approximately 300. Out of these forty, every year three students did not pass the second test.

4. Tight Focus on Students’ Ability to Apply the Rules of Grammar and Punctuation

To the extent possible, our assessments are designed to measure only a student’s ability to use the skills taught in the writing seminar program.[51] We believe that becoming a competent editor is a realistic goal for all students in a first-year legal writing course, and such competence is what we identify as proficiency. Moreover, the limited time in the writing seminars dictates the number of topics that can be covered effectively.[52] Thus, we avoid teaching and testing vocabulary associated with grammar and punctuation, although we do associate names with the concepts of parallel structure and passive voice because we find those topics are difficult to assess unless students explicitly identify the concepts. In general, for example, students need only demonstrate knowledge that a comma is needed or not needed at a certain point in a sentence, not be able to name the particular rule of the many governing comma usage, that applies.

To reduce interference from new students’ unfamiliarity with legal writing, the WSI uses vernacular English, not legal English. Thus, the assessment of students’ skills in editing grammar and punctuation is not muddied by regression in skills when students are asked to transfer skills from one context to another.[53] The writing sample for the first section of the WSI is in a genre familiar to entering students: the personal statement.[54] All students who apply to MSU Law have written a personal statement and have probably considered what makes such texts effective. Thus, we hope that students have not only interacted with the genre in question as readers, but as authors with a vested interest in the efficacy of such documents, extending their familiarity beyond that of a novice. Because failure cannot be attributed to transfer problems, we are confident in outcome of the WSI as a reliable measure of skill in grammar and punctuation.

Because we wish to test skills independent of reading speed and to limit the impact of visual processing speed and acuity, the PTs were essentially untimed during the study period.[55] Thus, we are not measuring how quickly students can read.[56]

IV. STUDY METHODS

A. Sample Size

We have data from 1,476 first-year students: five cohorts who started at MSU in the falls of the academic years 2007–2011.[57] The number of students in each cohort ranged from 282 to 367, with an average of 295.

B. Data Collection

1. Data Collected

The following objective measures of student performance were collected for every student during each year of the study and entered in a master data set for every student during each year of the study: WSI score, the student’s answer for every question on the WSI, first (fall) PT score, the student’s answer for every question on the PT, attendance at each optional writing seminar, participation in office hours, fall and spring semester writing grades, and first year GPA. For the earlier cohorts of students that have graduated, graduating GPA and bar passage on first try were also collected. In addition, qualitative data were collected via the course evaluations students completed at the end of each fall semester.

2. Student Achievement Data: WSI and PT Scores and Responses

Students recorded answers for the multiple-choice questions on the WSI and PT on OCR answer sheets (similar to SCANTRONs). We advised students to mark preferred answers on the original testing documents as well, in case of a marking error on the OCR form. The MSU Scoring Office processed tests using the GRADER III[58] system, which generated several reports, including detailed feedback for students, overall scores, item analysis, and basic histograms. The Scoring Office’s “Data Files,” containing student response data and raw scores, were used for some of the student data itemized above.

3. Student Engagement Data: Writing Seminar Attendance and Office Hours Participation

Data were collected on each student’s engagement with the optional instructional resources available.[59] Students signed in at writing seminars, and the writing specialist recorded attendance. The writing specialist also recorded individual student attendance at office hours. For the purposes of this study, we only analyzed attendance at office hours between the date of WSI, during orientation, and the PT in November. While students, of course, continued to attend office hours after the November PT, these data were not included, as they occurred outside the study period.

4. Instructional Efficacy Data

The combination of assessment data and data about student engagement allows us to track the effectiveness of the seminars and office hours.

5. Predictive Data: Final Grades and Bar Passage

To study the relationship between students’ scores on assessments and subsequent measures of student success, grades for fall and spring semester writing courses, first-year and graduating GPA, and bar passage were obtained from the MSU Law registrar’s office. As said above, the timing of this Article means that some students have not yet graduated; thus, GPA and bar data were unavailable.

V. Results and Discussion: Student Outcomes and Engagement

A. Positive Student and Faculty Reception of the Writing Seminar Program

The faculty of the law college has enthusiastically embraced the writing seminar program. The legal writing faculty finds the seminar program to be effective and useful as it shifts primary responsibility for grammar and punctuation to the writing specialist and allows the legal writing professors to spend more class time on other topics while remaining confident that students will learn these fundamental skills.[60] The other law college faculty members have also been very supportive. The writing specialist recently became the first member of the teaching staff without a J.D. to become a clinical faculty member with a rolling contract. Just Writing, the text for the writing seminars, is used as a resource in many upper-division courses. The writing specialist is often asked by faculty members, both clinical and tenure-stream, to give seminars at the clinics and to journals and law review and also to help support students with upper-level writing projects, including academic papers, law review notes, and writing samples.

More importantly, and perhaps surprisingly, first-year students have enthusiastically embraced the writing seminar program.

Figure 1 plots the simple percentage of students who attended any one of the five seminars offered. As the figure makes clear, an overwhelming majority of students attend at least one of the writing seminars during the fall semester. As no student is required to attend a writing seminar, this attendance reflects widespread, voluntary engagement with the program.

Figure 2 further disaggregates participation among students and demonstrates that the strong attendance result just described is not driven by students who only attended a single seminar. To the contrary, the modal observation in our data is a student who attends all of the five seminars offered during the fall semester. Sixty-two percent of our students attended a majority of the seminars.

Qualitative evidence also suggests widespread student engagement and satisfaction. Student evaluations of the writing seminar program during the years of this study revealed scores consistently between 4.4 and 4.8 out of 5 possible points in the areas of Course Organization, Course Materials, Professor Availability, and Overall Professor Effectiveness. First-year students frequently contact the writing specialist via email to relay successes and accomplishments related to the seminar material. One first-year student echoed a common sentiment in an email to the writing specialist: “The classes were really helpful, and I can seriously see an improvement in my writing for Advocacy [second-semester legal writing class]!” Even second- and third-year students continue to report long-term success. One second-year student reported on a family issue involving a hired lawyer and the impression this lawyer made: “The pleadings were riddled with these types of mistakes. It’s good to know that I’m starting to get the rules.” A third-year student reported that “of all of the material from 1L [year], I have found myself referring to your writing seminar slides countless times in the spring, summer, and 2L fall. The first slides on commas I open at least a couple times a month.” Particularly pleasing is the fact that some students even report enhanced self-awareness and self-efficacy with regard to their writing. A second-year student wrote, “I was able to recognize a sentence [containing] passive voice in my memo, and I was able to revise it! I know it may sound lame, but even though I have not mastered punctuation and grammar, I know that I am learning how to get better.”[61]

B. 100% Student Proficiency by the End of the 1L Year, Regardless of Entering Scores

Entering students began the writing program with the WSI illustrated below in Figure 3, which shows the distribution of scores on the WSI. The WSI consists of 32 multiple-choice questions. The x-axis of the figure provides the range of scores, and the y-axis indicates the percent of students receiving a particular score. The average score on the WSI across the five-year study period is 22.3 out of 32 with a standard deviation of 4.3. The median score is 22. The fact that most students scored below 24, the score for proficiency on the PT, on a test in vernacular, not legal English, confirms the general perception on the part of the law faculty that many students, despite generally strong undergraduate GPAs and intellectual strengths, enter the law school unfamiliar with the fundamental rules of grammar and punctuation that the writing seminar program teaches and assesses.[62]

Student scores on Figure 3 are divided into three regions—low, medium, and high—by two dashed vertical lines (appearing between 19 and 20 and between 25 and 26). As discussed above, when the results of the WSI were returned to students, each student was given information tying particular scores to steps that would maximize the likelihood of achieving proficiency on the first PT, at the end of the fall semester. The information focused on the future and on student effort, minimizing any reference to students’ innate ability or inadequate past. This emphasis primed students to consider help seeking as a positive step to obtain outcomes within their control, which has been shown to enhance help seeking, and thus, in this case, boost attendance at the writing seminars and office hours.

The approximately 25% of students, those who scored below 20 are identified as low-scoring students. These students were encouraged to contact the writing specialist to develop a plan for the semester.[63] Just under 51% of students, those with scores between 20 and 25, are in the middle group. These students were encouraged to evaluate the items they missed on the WSI to see what patterns emerged and attend the appropriate seminars.[64] Roughly 24% of students, achieving scores of 26 or higher, were high-scoring. They were encouraged to determine what, if any, items they missed and review using the textbook or attend the pertinent writing seminar.[65]

Student outcomes were highly satisfactory for all five years of the study. As said above, all 1,476 students participating during the study period scored at the proficient level by the end of their first year in law school. Thus, over the course of a year in the writing seminar program, even students scoring as low as nine or ten on the 32 question WSI in vernacular English improved to a minimum of 24 correct answers out of possible 32 when tested on the same skills in the context of legal English by the third PT.

C. Significant Improvement or Proficiency by the End of the Fall Semester for a Vast Majority of Students with Reduced Disparity in Their Skills

Figure 4 provides a closer look at student progress in the fall from WSI to PT score by plotting each student’s WSI score against the student’s later PT score, aggregated into a sunflower plot.[66] The x-axis shows WSI scores. The y-axis shows scores from the PT at the end of fall.

The unique—and potentially confusing—feature of a sunflower plot is the way it portrays multiple students with the same set of WSI/PT scores. A single dot represents an individual student with a particular WSI Score-PT Score pairing. Once more than one student achieves the same pair of scores, each student is instead represented by a line segment, which is often referred to as a “petal.” For example, there were two students who scored 15 on both the WSI and the PT. Similarly, towards the top right corner of the figure, a point with five petals represents five students who scored 28 on the WSI and then scored a perfect 32 on the PT. Each additional petal denotes another student with that pair of WSI/PT scores. Thus, the denser the petals (e.g., WSI = 25, PT = 29), the more students are represented as having progressed from those particular WSI scores to PT scores.

The diagonal, solid line between the lower left and upper right corners of the figure allows easy assessment of whether students scored higher or lower on the PT than on the WSI. Points above this line correspond to students whose scores on the PT were higher than their scores on the WSI. Conversely, students below the line have PT scores lower than their original WSI scores. And, of course, score pairings on the line itself indicate that a student had identical scores on both tests.

The vast majority of students (88%) show an increase in score between the WSI and the PT. The average score on the WSI is 22.3 with a standard deviation of 4.3; the median WSI score is 22. The average score on the PT is 27.3 with a standard deviation of 3.3; the median PT score is 28. Thus, the typical student scored substantially higher on the PT than on the WSI. Only 8% of students decreased in score between the tests.[67] The remaining 4% stayed the same. Because only the PT is in legal English, we can be confident that this improvement did not occur due only to greater familiarity with legal English as the first semester progressed. In fact, the switch to legal English for the PT probably put greater strain on the students’ skills.[68]

The amount of vertical distance between a score pairing and the line represents the magnitude of the changes in students’ score between the two tests. Score pairings far above or below the line show comparatively larger net changes between the WSI and the PT. Again, as will be confirmed in Figure 5 below, the plot reveals the extent to which students who scored lower on the WSI, that is, students on the left of the figure, showed the greatest gains, often large ones.

Besides general improvement, the dashed horizontal line also indicates the significance of the students’ scores across the plot at a value of a score of 24 of the y-axis, or the PT score required to demonstrate proficiency and to pass the test. Students scoring at this value or above have completed the program. By the end of the fall semester and the writing seminars, 87% of students in the five-year study period have PT scores of 24 or higher. The plot indicates that nearly 700 students scored below 24 on the WSI, but nevertheless achieved 24 or above at the end of the fall on the PT. These students fall left of the mark indicating 24 correct on the axis indicating WSI scores, but above the line for proficiency. Further, and equally importantly, as evidenced by the smaller standard deviation on the PT results than the WSI, performance is less widely dispersed around the average scores on the PT than it was around the lower average on the WSI. This means that over the course of the fall semester, there is a reduction in the disparity in skills evidenced by entering students. Particularly gratifying are the individual success stories hidden in the dots on the upper left corner of the plot. These are students who scored below 16, that is below half, correct on the WSI, yet at the end of the fall, these students scored 30 or above: one student’s increase was 21 points, from an initial score of 9, less than one-third correct, to a final score of 30, almost perfect.

On the other hand, the students who scored comparatively well on the WSI, thus indicating that they were more accomplished writers or editors from previous academic writing experiences, were the most likely to show a decrease in scores, perhaps because they were the least likely to attend writing seminars, as discussed below, coupled with the transition to legal English. These students fall below the diagonal line in the upper right corner of the plot. This distribution conforms to the theory, discussed above, that students who are proficient in another discourse or genre often have a harder time adjusting to the changed demands of a new genre, perhaps because of self-perception as already proficient writers.[69] Nevertheless, except for a very few outliers over five years, even students whose scores decreased remained clustered relatively near the diagonal line, indicating that while improvement may not be universal, pronounced decreases in scores were unusual.

Students located below the horizontal line, that is who scored below 24 on the PT, continued with additional instruction and testing until they could demonstrate proficiency on a subsequent test. The students who occasioned us the most distress were those very low-performing students on the left of the figure who, despite very large gains in scores between the WSI and the PT, still did not manage to show proficiency and needed to continue on in the program. However, for the most part, these students did not register dissatisfaction. On the contrary, they were generally happy with their improvement and understood the need to continue with further study that they felt would be rewarded. One student who did not pass the first PT commented, “I feel as though failing the first test was actually a long term benefit for me as it caused me to learn and understand the rules [of writing and grammar].” Upon passing the PT on the third and final try for the year, another student commented, with uncharacteristically unrestrained capitalization and punctuation, “OH MY GOODNESS! Thank you!!! I feel like I just won the lotto or something!” Not only did this student feel personal satisfaction for having passed the test, she immediately requested “to go over the questions I got wrong,” even though she had no obligation to do so. As indicated by the engagement numbers discussed above, we argue that affirming student autonomy, including for those students who make choices that we might not prefer, is an important part of the success of the program.

The widespread improvement, that exceeds the 83% of students indicated in Figure 1 as accessing the optional writing seminar program, may also indicate the importance of the integration of the writing seminar program—via coordinated instruction and feedback—with the legal writing classes. Such integration may work not only to promote engagement with the writing seminar program, but also to enhance or consolidate skills in those students who chose self study as opposed to attendance at writing seminars or office hours.

D. Greatest Fall-Semester Engagement by Students with the Lowest Level of Skill

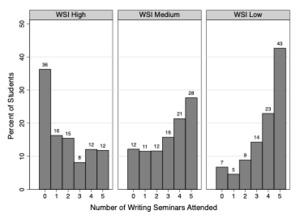

Figures 1 and 2 above have already indicated the high level of student engagement, but a frequent problem with courses perceived as remedial is attracting the very students who may benefit most.[70] We wished to know which students were attending the writing seminars and how often. The writing seminar program bills itself as for all students and as professional development, not remedial skill building. However, as discussed above, feedback provided to each student with his or her results on the WSI does recommend courses of action depending on score on the WSI. Here what is of interest is the ability to attract low-scoring students to the seminars and the impact of information returned with the WSI on writing seminar attendance. Figure 5 suggests the writing seminar program is successful in motivating low-scoring students to attend while not sacrificing the higher-scoring students who could benefit from instruction.

Along the x-axis, we plot each of the three WSI Score Category feedback types and the number of seminars attended. The y-axis shows the percentage of students attending that number of seminars for each group. As the height of the bars makes clear, we observe the highest level of attendance by students in the low WSI Score Category; conversely, the high group is most likely not to attend any seminars—by a five-times-higher percentage than the low group—and has the smallest percentage of students attending all seminars—less than half the percentage of the medium group and less than one-third the percentage of the low group. Medium students attend 71% more seminars, on average, than do high students.[71] Another way to understand this is by comparing students within categories: of students with low WSI scores, 93% attend at least one seminar; of students scoring in the middle on the WSI, 88% attend at least one seminar; and finally of students scoring high on the WSI, only 64% attend at least one seminar. Further, although 28% of all students attend all five seminars, the scores by group are as follows: 43% of low-scoring students attend all five seminars, 28% of medium-scoring, and 12% of high-scoring.[72] Thus, while there is significant participation across student groups, those with the lowest skills are voluntarily attending the seminars in greater proportions and more consistently.

E. Greatest Fall-Semester Gains for the Students with the Lowest Scores on the WSI and the Most Involvement with the Writing Seminar Program

Engagement as measured by seminar and office hour attendance is linked for all students with performance gains between the WSI and PT and proficiency on the PT.

First, we examined the individual student score changes between the WSI and the PT, which we descriptively summarized in Figure 4. Our dependent variable is the change in each student’s score, which ranges between -8 (i.e., the student scored 8 points fewer on the PT than on the WSI) and 21 (i.e., the student scored 21 points higher on the PT than on the WSI). The average score change is 5 points with a standard deviation of 4.1. To explain this variation in score change, we consider several factors. Consistent with our contention that engagement in our program is beneficial, we include the number of writing seminars that the student attended. This variable ranges between 0 and 5 with a mean of 2.9 and a standard deviation of 1.8. In a similar vein, we also include the number of times that a student visited a writing specialist for office hours. This variable ranges between zero and seven[73] with a mean of 0.28 and a standard deviation of 0.88.[74]

Figure 6 breaks out the improvements suggested above more precisely by low-, medium-, and high-scoring students and attendance at writing seminars, indicating that, as hoped, the program helps all students, but benefits most those who most need to improve their writing skills.

Students in the low category of WSI scores, who comprise one-fourth of students in our data, typically achieve score gains of about nine points between the WSI and the PT, with average WSI and PT scores of 16.6 and 25.3, respectively. Comparing average scores for this group of students shows a relative increase of approximately 52%. Fully 71% of the students in this category achieve proficiency on the PT. Students who attend at least one writing seminar can expect to score over two points better than students who never attend a seminar. However, all students who start with a low WSI score can expect to improve their scores by 6.5 points. The improvement for students who did not attend writing seminars may be due to the integration between the legal writing classes and the writing seminar program. As discussed above, students received a separate writing grade and writing checklist for major assignments that not only identified errors, but keyed those errors to the sections of the textbook where they are discussed.

The 51% of students whose WSI score placed them in the medium category also show gains between the WSI and the PT, although not as substantial as students in the low category. These students have average WSI and PT scores of 22.5 and 27.5, respectively. The median score change for the majority of students is five points, with a relative score increase of approximately 22%. Again, a two-point additional gain is shown for students who attend at least one writing seminar. In terms of achieving proficiency on the PT, 90% of students in this middle group will do so.

Finally, students with the highest scores on the WSI show the lowest gains on the PT. A typical score increase for a student with an initial WSI score of 26 or greater is just two points; those who do not attend any writing seminars improve less than half a point. The relative score change for these students is just 5%. As discussed in the context of Figure 4, some students who have high scores on the WSI actually achieve lower scores on the PT. However, for those who do improve, it is worth remembering that these students’ WSI scores are already very high, which leaves comparatively little room for improvement since the maximum score on the PT is 32. Twelve percent of WSI high category students end up achieving this perfect score.

In addition to the lecture-and-workshop format writing seminars, the writing specialist, during the study period, offered twenty to thirty office hours per week available to students by appointment and drop-in basis. Office hours could focus on preparing for assessments, but more often, students chose to focus on their draft papers for their legal writing courses, seeking editing support and technical advice on revision. Attendance at office hours is associated with increased scores, although the difference is less dramatic than attendance at least one writing seminar. This is indicated by Figure 7.

Unlike writing seminars, office hours are limited. Further, students identified as greatly in need of help could be referred to the writing specialist by legal writing professors. Such students, if they wished, could sign up for weekly office hours, further reducing the availability of office hours for other students. Thus, as expected, the students with the lowest WSI scores show the greatest gains, 1.5 points, for office hour attendance.

The overall impact of engagement with the writing seminar program is indicated in Figure 8. This figure indicates the escalating improvements experienced by students as they engage more with the program.

Here, “None” denotes a student who neither came to any writing seminars nor attended office hours. “L”[ow] denotes a student who either came to 1–2 writing seminars but attended no office hours. “M”[edium] denotes a student who attended 3–5 writing seminars but never attended office hours. “H”[igh] denotes a student who attended 3–5 writing seminars and at least one office hour. We use the value of 3 for writing seminars as it corresponds to the sample median. In terms of office hour attendance, approximately 15% attended at least one office hour session.

All students can anticipate some improvement, which we attribute in large part to participation in the legal writing course, in which they received grades on grammar and punctuation, writing checklists indicating their errors and keyed to the textbook, and varying levels of explicit, in-class instruction depending on the professor. The greatest gains here and throughout are just where we would like to see them: the students with the lowest entering WSI scores. For all students, a low level of engagement resulted in very little additional improvement—less than one point. Much greater gains were experienced by students as they engaged at a medium, and even more, at a high level.

These score gains translate into higher rates of achieving not just improvement, but proficiency, on the PT as demonstrated by Figure 9.

As expected, students who scored high on the WSI to begin with, thus indicating the highest level of skill at entry to law school, show the smallest gains, but the highest rates of proficiency. All of these students scored at least a 26 on the WSI. Proficiency on the PT is set at 24, although the PT is in legal English, not the vernacular. Students in the high group can virtually guarantee proficiency through high engagement: One hundred percent of those students over five years were proficient. Students in the medium group could also virtually assure proficiency through high levels of engagement: 97% of those students would be proficient by the end of fall semester. Not surprisingly, students who demonstrated poor skills on the WSI (i.e., the low group) fared worst on achieving proficiency. These students scored between 9 and 19 on the WSI. Thus, even without the transfer to legal English for the PT, they began the fall semester at a significant disadvantage. However, 77% of these students could expect to attain proficiency in their first semester of law school after high engagement with the program.

The above figures show that score gains between the WSI and PT are not random, but rather appear to be driven by both a student’s baseline level of knowledge (as measured by the WSI) and that student’s level of engagement with the program. Although these results are certainly encouraging, as the analysis is descriptive in nature, it is necessarily limited in what it can tell us about how the interplay of these various factors affect a student’s score change. Accordingly, to provide a more systematic account, we turn to multivariate analysis and, in particular, multiple regression analysis, which allows us to examine the impact of particular factors while statistically controlling for other potential confounding variables.

Our initial dependent variable is the change between each student’s WSI and PT score. As we note above, there are meaningful differences in score gains across the different student groups as distinguished by low, medium, and high scores on the WSI and engagement. To account for these differences, we include a dichotomous indicator for each of the three categories. Substantively speaking, this approach allows us to ask if, after controlling for a student’s initial WSI score group, the remaining variation in score change can be explained as a function of attendance at writing seminars and office hours.[75]

Given the nature of our dependent variable, we estimate a linear regression model. Parameter estimates for this model are reported in Table 1.[76] The results suggest the model fits the data well, explaining about 44% of the variation in score changes with the five independent variables we include in it. The model results indicate that there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between both of our measures of student engagement and PT score for all three student groups. That is, as the number of office hours a student attends goes up, so too does her expected score gain between the WSI and the PT. Similarly, higher attendance at writing seminars also yields a higher expected score change.

The model’s output allows one to estimate the score change for a hypothetical student conditional on the student’s WSI Score Category and her attendance at both office hours and writing seminars. Generating such estimates requires three basic steps. First, we must decide if a student is in the high, medium, or low WSI Score Category and select the appropriate coefficient for that category. If, for example, we were interested in estimating a score gain for a low student, then we would select 6.368, which is the coefficient for that category. Second, we need to specify how many office hours and writing seminars a student attended. Third, we substitute these values into the linear equation to calculate an estimated score change. For a student in the low WSI Score Category, that equation would be: Gain = 6.368 + 0.230 x Office Hours + 0.577 x Writing Seminars, where “Office Hours” and “Writing Seminars” refer, respectively, to the values we selected in step two. Thus, if we picked the modal values for these two measures (0 office hours, 5 writing seminars), then the resulting equation would look like: Gain = 6.368 + 0.230 x 0 + 0.577 x 5, which simplifies to 9.253. That is, for a student in the low WSI Score Category who attends all five writing seminars and no office hours, our best guess is for those efforts to gain her about 9.3 more points on the PT than she scored on the WSI. We can then tweak aspects of this counterfactual to see what would happen if she attended no seminars instead of five. After adjusting the previous equation, we would find that this revised student would be expected to observe a 6.4 point increase in her score, which represents a 31% relative decrease from the gain if all five seminars were attended. These increases are consistent with what we observed in the descriptive analysis presented earlier.

More generally, we can also ignore a student’s initial WSI score and make the general statement that every additional writing seminar attended will translate into roughly 0.6 additional points gained on the PT. Thus, going from zero to five seminars will net a student roughly 3 points on the PT. Similarly, each additional office hour attended will yield roughly 0.2 additional points on the PT. A student who attended zero office hours would be expected to gain about one point less than a student with a very high level of office hour attendance (i.e., five sessions, which is roughly the 99th percentile of the sample data).

It is encouraging that engagement in our program yields statistically and substantively meaningful gains in student performance. However, these results do not speak to the interaction between student engagement in the program and student ability to move from a lower score on the WSI to a proficient score of 24 or above on the PT. To evaluate the effect of program engagement on proficiency, we conducted a second statistical analysis. Here our dependent variable is simply whether a student obtained a proficient score on the PT (i.e., scored 24 or higher), which we code as 1 if the student did and 0 if the student did not. Our independent variables remain unchanged from the previous analysis—i.e., attendance at office hours and writing seminars. Our dependent variable is dichotomous, so we estimate separate logistic regression models for each of the three values of WSI Score Category.[77] Parameter estimates are presented in Table 2.[78]

The results from this model reveal two interesting findings. First, for all values of WSI Score Category, we fail to find a statistically significant effect for attendance at office hours for any group of students. This runs contrary to our expectations and the results we obtained in our model of score change, where the variable was statistically significant. Second, in terms of our writing seminar attendance variable, although the coefficient on the variable is positive for all three WSI categories, we only recover a statistically significant effect for students in the medium and low WSI groupings. In other words, attendance at writing seminars is positively related to whether a student achieves proficiency if his or her initial WSI score was medium or low, but such attendance has no systematic effect on proficiency for students who scored highly on the WSI.

Unlike the previous model, which was a basic linear equation, a logistic regression model is non-linear and the results are somewhat more difficult to interpret. To aid us in that endeavor, we calculated a series of predicted probabilities, which we portray graphically in Figure 10, which shows the substantive impact of writing seminar attendance for all three values of WSI Score Category. Along the x-axis we show the number of seminars a hypothetical student attended, which ranged between 0 and 5. The y-axis shows the likelihood that a student achieved proficiency on the PT. The three different lines within the plot itself indicate the likelihood for students in each range of the WSI scores: high, middle, and low.

Starting with a student in the high category, we see that she is, in general, very likely to achieve proficiency on her initial attempt. Indeed, for such a student we estimate between a 97 and 99% chance that she will be proficient, an estimate that is consistent with the actual values we observe in our data (see, e.g., the left side of Figure 10). We also observe only the weakest of increases in proficiency likelihood as the number of writing seminars attended by a student with a high WSI score increases. This corresponds to the result from the underlying model, which indicates that seminar attendance has no impact on a high student’s likelihood of proficiency.

Moving to a student with a medium WSI score (i.e., the middle line in the figure), we find that this student also has a relatively high baseline likelihood of being proficient, which is to say a relatively high likelihood of passing even without attendance at the seminars. For such a student, however, unlike her high-scoring counterpart, the effect of seminar attendance is statistically significant. In substantive terms, we estimate that going to 5 seminars as opposed to 0 seminars results would increase the likelihood of proficiency from 85% to 93%—a relative gain of about 9%.

Finally, we turn to a student with a low WSI score. For this individual, attendance at seminars has the most positive impact, as the slope of the lowest line makes clear. Indeed, if a student with a low score on the WSI attends no writing seminars, then we estimate that this individual has just over a coin flip’s chance of being proficient on the PT (about 56%). However, a similar low-scoring student who attends all five writing seminars sees the likelihood of proficiency jump to 74%—a relative change of 32%. This impact indicates that the writing seminar program is helping precisely those students at whom it is targeted: students who lack skills in grammar and punctuation at the beginning of fall semester.

VI. Results: Correlations Between Performance on the Assessments, Seminar Attendance, and Other Measures of Success in Law School

The primary goal of our program is to ensure that all students achieve a baseline level of proficiency in writing. We know that they do, and these results confirm that their ability to do so is, in large part, due to the various components our program implements. More generally, however, we were curious about the predictive value of the WSI. There are a variety of quantitative indicators used to measure a student’s success during law school. Of these, undergraduate GPA and LSAT are used, of course, to make admissions decisions and to identify students who may need assistance. Additional predictors like first-year GPA, which can be used for intervention with at-risk students, come too late.[79] As educators, we are interested in being able to identify matriculated students early in their law school careers who are potentially at risk of performing poorly in their first year and beyond.

Thus, we conducted two exploratory analyses. First, we sought to examine the ability of performance on the WSI to predict a student’s final law school grade point average (GPA). To do so we simply combined our WSI scores with law school GPA data obtained from the registrar. We then regressed a student’s final GPA on a series of independent variables using linear regression. The results of these models are reported below in Table 3. Model 1 reports a bivariate regression between a student’s WSI score—which takes place, recall, in fall of her first year of law school—and a student’s final law school GPA. We find a positive and statistically significant relationship. In Model 2, we add the additional control of a student’s final PT score, finding that both of these measures are positively correlated with a student’s final GPA. Models 3 and 4 up the ante, as we now control for a student’s GPA at the end of his or her first year of law school. As one might expect, there is a very strong relationship between first year and final GPA (the bivariate correlation is 0.91). Nonetheless, we still find a small but positive and statistically significant relationship between a student’s WSI score and her final GPA, even after controlling for her GPA at the end of the first year of law school.

The second predictive relationship we considered was first-attempt bar passage. These data also come from the registrar and were obtained for 645 students. Our dependent variable is whether a student passed the bar on that student’s first attempt (0 = no; 1 = yes). 90% of the students in our data were coded as “1’s.” Our single independent variable is a student’s WSI score, which ranges between 9 and 32. As our dependent variable is dichotomous, we estimate a logistic regression model and recover a statistically significant relationship between bar passage and a student’s WSI score. Given the non-linear nature of our model, we present our results graphically in Figure 11 below.[80] The x-axis shows a student’s WSI score. The y-axis shows the likelihood that a student passed the bar on the first try. As the plot reveals, there is a positive relationship between WSI Score and the likelihood of passing the bar. We estimate, for example, that a student with the sample minimum value of 8 on the WSI has approximately a 78% chance of passing the bar. By contrast, a student who achieves a perfect score on the WSI has roughly a 95% chance—a relative increase of approximately 22%. Or, stated differently, a student is over four times more likely to fail the bar on her first attempt when she has a low WSI score than when she has a high score.

Interestingly, when WSI score and writing seminar attendance are included in this bar passage model, both variables are statistically significant and positive.[81] Thus, just as WSI score predicts bar passage, as shown in Figure 11, whether a student attends writing seminars similarly predicts bar passage. When WSI score is held constant, students’ chances of passing the bar on the first attempt increase from 85% if they did not attend any writing seminars to roughly 95% if they attend all five seminars, as shown in Figure 12. In other words, regardless of whether a student started with a low WSI score or a high WSI score, that student’s chance of passing the bar on the first attempt increased the more often that student attended the voluntary seminars. This finding does not suggest that the seminars are in some way teaching bar content or even teaching strategies students might use on the bar. Instead, it is entirely possible that the mere fact of students seeking help is an attribute that is, in some way, correlated with success on the bar.

We present these data not so that such students can be ranked earlier in law school or eliminated altogether, but so that as with the WSI itself and the score sheet and recommendations we return to students in our writing seminar program, students can be warned about the significance of these data and given options to enhance the possibility that they can achieve their goals, in this case passing the bar and becoming an attorney. Our experience with the writing seminar program suggests proposing resources that the students can embrace as contributing to professional identity and success while students maintain autonomy and control of the timing and their choices. This arrangement empowers students to take their own steps to ensure their own success. The data seem to suggest that, regardless of entering skills with grammar and punctuation, taking these steps of their own accord has a positive effect on bar passage three years later.

VII. Conclusions and Implications

The first and most obvious conclusion from our study is that law faculty and administrators are correct in thinking that many students do not enter law school with the fundamental writing and editing skills necessary in law school and even more necessary in practice. The response to this situation may vary depending on the philosophy of the law school, but we believe that schools have an obligation to equip matriculated students with the tools to succeed, particularly in situations where the gaps in students’ knowledge pre-date law school and may well be due to simple lack of instruction. These gaps are known to undermine success or even employment in the legal profession. Explicit instruction in such material, here fundamental writing mechanics, shrinks student differences deriving from pre-existing social capital and focuses law school evaluation on the proper data, students’ legal abilities.

Within the context of a commitment to reducing student disparity and cultivating necessary skills in future legal professionals, our data strongly support the effectiveness of a proficiency model instead of a ranking model, as the basis for instruction in these skills. A proficiency model is based on the high expectation, for both teachers and students, that all students will rise to a proficient level before instruction is ended. While we recognize that a proficiency model demands much of professors and of students and may not be appropriate for every course, we encourage its use in the context of clearly identified fundamental skills necessary to all who enter the legal profession. We believe it is particularly appropriate in the context of the first year of law school, during which students acculturate at different speeds to the new world of the law.

Further, our engagement and efficacy data provide some answers to one objection to the proficiency approach, particularly when engagement is at least to some degree voluntary, because it is not driven by grades or attendance requirements: that in the context of the competitive first year, students will not engage with a course run on a proficiency basis because such a course may not contribute to a student’s GPA or class rank. Students are informed from the beginning of the program that they will not receive their second-semester writing grade until they pass the PT. However, failure to pass or even take the test has no impact on their grades. Yet only a handful of students fail to take the test the first time it is offered in the fall semester. Further, attendance data for the writing seminars and demand for office hours indicate that fears that classes offered on proficiency basis will be neglected are misplaced. Honoring student autonomy while engaging their professional aspirations through instruction presented and perceived as fundamental to their future role as attorneys can be highly motivating for students.

This instructional paradigm also promotes other long-term goals of legal education. It prompts help seeking in students most in need of instruction. In all students, it promotes intrinsic motivation for learning and enhances self-regulation, development of which is critical for long-term success in the legal profession. The approach reduces student passivity and stress, leading to a more positive experience not only for students, but also for the professor, who is able to work with engaged and positive students. Finally, as indicated by figure 11, student engagement in a voluntary program is positively correlated with first time bar passage. Thus, creating an environment in which students are enabled to and more likely to engage in voluntary resources could demonstrate positive effects. Additionally, this finding suggests that law schools would be well-served to pay attention to, and perhaps even track, how and when students access available resources.

Finally, implicit in our approach is an argument that legal educators should, whenever possible, use formal data collection to guide program design, instruction, and assessment. We hope our study models a way to assess the effectiveness of pedagogical models and instruction. Our early decision to incorporate data collection and to think about what type of data to collect shaped our program and instruction The resulting information will allow professors and institutions to assess what courses and strategies are promoting the desired student outcomes most effectively—and change those that are not effective. Quantitative data has an important role to play in this endeavor; it moves the discussion beyond subjective interpretations of students or instructors. Using data eschews anecdotal evidence in favor of objective measurements of the success or failure of both sub-populations of students and students as a whole. Thus, we are able to base future decisions on the relationship between those outcomes and the design and delivery of instructional programs. This shift in emphasis has the potential to improve the experience of all students, but most importantly it has the potential to improve the experience of those students most dependent on law school instruction for their success.

For preparing students for practice with a focus on their future clients, see Roy Stuckey et al., Best Practices for Legal Education: A Vision and a Roadmap 16–18, 39–40, 62 (2007).

Of course, the problem is not limited to attorneys: “Managers are fighting an epidemic of grammar gaffes in the workplace, the Wall Street Journal reported . . . [s]ome bosses and coworkers step in to correct mistakes. Some offices provide business-grammar guides to employees. And almost half of employers are adding language-skills lessons to employee-training programs.” Bryan A. Garner, The Year 2012 in Language & Writing: June, LawProse, http://www.lawprose.org/the-year-2012-in-language-writing/ (Dec. 29, 2012, 12:21 a.m.) (discussing articles in the Wall Street Journal and New Times, in June of 2012). In other industries, grammar skills are highly valued by employers. Even a sheet-metal-manufacturing business owner noted, “‘My operators are in constant contact with our customers, so they need to be able to articulate through e-mail. But you’d be surprised at how many people can’t do that. I can’t have them e-mailing Boeing or Pfizer if their grammar is terrible.’” Id. (quoting a business owner).