I. Introduction: Through Our Eyes, or through Theirs?

Several years ago, I was teaching a blind student how to use LexisNexis. He was working on his laptop, using a software program[1] that read aloud the content of each web page we accessed. At one point, I suggested that he “scroll down.” He was puzzled. Although he was hearing every bit of information on that screen, he had no frame of reference for the spatial organization that I was so accustomed to seeing with my eyes. And to him, that spatial organization was irrelevant anyway. He wasn’t accustomed to receiving information that way, and he certainly didn’t see why anyone would need to scroll down to read on. His frame of reference was so different from mine that we didn’t share a common vocabulary, at least on that particular point.

The same could be true of the next generation of lawyers and their current legal research professors.[2] We have likely reached a point at which our frames of reference diverge sufficiently that we don’t share a common reference point for approaching the structure of legal research.[3] Arguably, the tech-saturated millennials need a solid research foundation more than any generation before them.[4] Yet many of them regard our legal research instruction as cumbersome or outdated.[5] Having grown up using intuitive electronic devices, and using them to good advantage,[6] many modern law students resist legal research methods that require rigidity, formality, or—worst of all—a trip to a print library.[7] Indeed, many of them are downright “mistrustful both of physical libraries and of those who extol their virtues.”[8] And for our part, “bridge generation”[9] lawyers sometimes assume that new researchers need the same foundations that we needed when we first approached the subject. But are our assumptions valid? Or do we cling to them simply because that’s how our eyes have been trained to see things?

Viewed with fresh eyes, the legal research process bears little resemblance to past paradigms. Forget for a moment what we think we know about how best to research an unfamiliar legal issue. Outside the confines of past thinking, it becomes easier to contemplate what legal research looks like to those who are seeing it for the first time in the information age. Indeed, today’s law students are “digital natives”:[10] they grew up using the Internet as their primary means of gathering information. So while the sheer volume of information may seem unwieldy to us (the digital “immigrants”), native users find nothing particularly unusual about being hit with large amounts of data at one time. And they do not view research as a linear process.

As a result, many legal research paradigms can feel like proverbial “square pegs.” They don’t quite fit the knowledge “hole” that legal research teaching must fill. But with a fresh look at legal research, a new reality emerges. Paradigms anchored too firmly to specific media, sources, or linear models are becoming ineffective compasses for navigating the legal research process in the information age. In their place, a non-media-dependent approach, one focused on categorizing information rather than on gathering it, can provide a more intuitive guide for digital natives.

This Article will advocate for fresh thinking about legal research. First, it will acknowledge the challenges that new technologies bring to the legal research classroom. Next, it will consider the limitations of existing legal research paradigms, as well as some new “truths” about research in the information age. Finally, it will propose a flexible legal research paradigm that de-emphasizes the information-gathering process and focuses instead on the importance of understanding and analyzing legal authority.

II. Teaching Legal Research in the Data Smog[11]

Lexis Advance,[12] Google Scholar,[13] Oyez,[14] and Justia.[15] Paperless, wireless, hands-free, and voice-activated. Rushing to learn the “next big thing,” only to fall behind yet again. No doubt about it: information technology is marching—no, sprinting—ahead, fueled by new products that promise to revolutionize law practice and make lawyers more efficient.[16] But at the same time, the feedback about law graduates’ research skills remains lackluster at best.[17] Despite a literal surplus of available tools, recent law graduates generally lack the research skills employers expect.[18]

And what does this mean to those of us trusted to teach this critical practice skill[19] to tomorrow’s lawyers? Are we tasked with forever chasing the latest product offerings and wedging them into an already over-full curriculum? Should professors strive to stay ahead of the Millennials so that we can teach them new technologies (or forbid them to use them) before they discover them on their own?

With the information-technology stampede showing no signs of stopping, legal research pedagogy cannot be about introducing publications or platforms or about dictating an order for consulting them. Quite to the contrary, it must be about establishing a true understanding of what it is that the researcher is looking for—and what to do with this information, which has become so dangerously easy to gather. We’ve reached an important crossroads. It turns out that “modernizing” legal research instruction has little to do with databases, gadgets, or mobile apps. It has more to do with freeing our minds (and our syllabi) of unnecessary clutter. It requires a renewed focus on the more substantive aspects of legal analysis. In short, the more that students know about legal analysis, the more confidently they will approach the research process, regardless of the tools they use or the order in which they use them.

Now, none of this is to say that we need not bother becoming familiar with what’s new on the technology front. In fact, we cannot avoid the task of staying current, and we must be ever mindful of the ways in which technology is affecting the evolution of law practice. But, at the same time, we need not be reactionary, giving up control of our legal research curricula to the winds of technological change. Nor should we be intimidated by the thought of teaching legal research to students who know more about technology than we do. Ultimately, legal research has less to do with tools and platforms and more to do with understanding and analyzing the law.[20] If we focus on teaching the latter, familiarity with the former will come more easily.

III. The Limitations of Existing Legal Research Paradigms

Much has been written about the need to fill gaps in law graduates’ legal research proficiencies. Of course, legal research has long been recognized as a core practice skill.[21] And the Carnegie Report[22]called upon law schools to better connect their legal-thinking pedagogy to law-practice skill development.[23] Many commentators, both recently and nearer the advent of the electronic-research revolution, have recognized the paramount importance of legal authority and analysis as critical components of legal research proficiency.[24] Yet there has been robust debate about the relative merits of the so-called “bibliographic” and “process-orientated” paradigms for teaching legal research.[25] In 2011, the American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) published its Legal Research Competencies and Standards for Law Student Information Literacy, consisting of five principles aimed at identifying the core research skills that practice-ready law graduates should possess.[26] Many scholars have published suggested paradigms and course-restructuring studies since Carnegie and the AALL information-literacy report, signaling positive movement toward better legal research skills for tomorrow’s law graduates.[27]

But most legal research paradigms, both existing and proposed, retain a linear foundation.[28] They dictate an order in which to consult sources, or they suggest that legal research can be reduced to a series of steps in a reasonably well-defined process.[29] Through the eyes of the modern law student, such frameworks often appear neither intuitive nor efficient.

There are two problems with the linear paradigm. First, a framework focused on the order in which to take certain steps (or a “comprehensive” list of sources to consult) suggests to the novice researcher that legal research is yet another information-gathering endeavor. Unfortunately, most students come to law school overconfident in their research skills because they are fairly adept at the simple task of gathering information.[30] So they often fail to appreciate that legal research is significantly more sophisticated and complex than the more-general research they have conducted in the past. And if we teach legal research with an emphasis on information gathering, then we inadvertently feed into this dangerous line of thinking.

Second, an overly rigid, “step-by-step” legal research process doesn’t resonate with most modern law students. In truth, Internet research is rarely linear, and digital natives are quite accustomed to sifting large amounts of information contemporaneously. Viewed from that perspective, a step-by-step process may not feel genuine. And if students don’t buy into the framework that we teach, then they won’t internalize a solid research foundation.

Beyond the student perspective, the very nature of current information technology calls for legal research teaching that emphasizes substance over format or formula. While legal research platforms are becoming increasingly easy to use, they are simultaneously making it more difficult for novice researchers to understand and analyze the results that they provide.[31] Thus legal research teaching should leave the method and means of information gathering to the researcher, focusing instead on the foundational knowledge necessary to accurately categorize the information and assess its completeness.

IV. A Few Simple Truths: Legal Research in the Information Age

A. It Is More Important to Known What It Is Than to Known How to Find It

Every day, it becomes easier to locate legal information.[32] Gone are the days of complicated search strings or telephone calls to the court for copies of the latest unpublished opinions. In fact, you don’t even need a citation to retrieve a published case these days.[33] And beyond the obvious benefits of ease and convenience, this is excellent news for legal research professors; we no longer need to teach the nuts and bolts of navigating arcane legal sources. In fact, most electronic sources are designed to be self-taught.[34] And because modern law students are “technological chameleons,” there’s little doubt that they’ll figure it out if they believe that it’s important.[35]

But, as noted, the avalanche of easily accessed information can make it increasingly difficult for new researchers to know what is important and what is not. Where books put concrete corners around information, electronic sources can seem to present the same information as seamlessly connected.[36] Quite often, Internet researchers care less about the nature of the information source than they do about its content.[37] And even the fee-based legal research providers no longer require researchers to make source selections at the outset. Instead, Lexis Advance and WestlawNext present results from multiple sources all at once, in response to what closely resembles a Google search.[38] Even after the researcher limits the results and focuses, for example, on case law, the results (regardless of jurisdiction, court level, or publication status) are presented as a one list,[39] almost suggesting—to the novice—that they carry equal weight.

So, although finding legal information has almost become a one-click process, intelligently using it remains a difficult skill to master.[40] To understand research and perform it well, students must be able to specifically identify a legal source when they see one—in any medium—and they must learn to question the nature of everything that they turn up along the way.[41] Even more fundamentally, they must understand exactly what authority governs a particular legal issue. This is far more critical than knowing the ins and outs of navigating the various platforms.

In fact, it’s probably time we stop spending any significant class time at all showing students where to click on Lexis and Westlaw. Let the student representatives demonstrate their products outside of class. Let the online tutorials, the certification programs, the live “chat” features, and the 24-hour-customer-service lines answer their technical questions. And, as professors, let’s be fine with the fact that we don’t always know where to click or how the newest mobile app works. For one thing, those concepts are moving targets, and professors are hardly expected to be their students’ personal IT departments. Moreover, most of the mechanics that we attempt to teach them in the first year will likely be obsolete by the time they graduate.[42] Finally, think back to the last time someone updated the look and feel of your favorite mobile application. Did you attend a live training session? Probably not. More likely, you toyed with it until you figured it out, or you “chatted” with an online representative if you had a question. When it comes to the bells and whistles of legal research tools, let’s let students do the same.

If professors spend less time teaching tools and mechanics, then they can spend more time teaching substance. For every hour spent teaching students how to access information (in books, on the paid services, or on the open web), professors should devote many more hours to assuring that students understand legal authority and gain significant experience actually working with it. This means more than incorporating a longer lecture about court structure or the legislative process. It means significant, hands-on experience where students practice recognizing and weighing authority in the context of widely varied research hypotheticals.[43]

The specific format for achieving this would, of course, need to be customized to fit within an individual law school’s curriculum. But here are some representative examples to consider. First, extensive library exercises, print-instruction units, or library “treasure hunts” could be replaced with quick-turnaround research simulations where media choice is left open. Or a school might “flip” the legal research classroom, pushing the lectures about gathering legal information out to podcasts or other out-of-class media, thus freeing in-class time for hands-on practice and discussions about legal authority in a variety of contexts.[44]

Of course, an age-old problem may persist. The less law one knows, the harder it is to know what law to find. Developing a significant substantive law foundation takes time, and this will remain a challenge without easy answers. It probably isn’t realistic to suggest that one can gain enough experience within a first-year legal research unit to become a widely experienced researcher.[45] But each additional experience is exponentially more valuable than the one to three experiences that most students get in the typical legal-writing class. Therefore, time shifted from teaching mechanics to practicing analysis will almost always be time better spent.

Sure, somewhere along the line, new researchers will need to figure out where to click. And in the (unlikely) event that they are working in print, of course they’ll need to update using pocket parts and the like. But inevitably, the more platform options we have, the more personal the mechanics of legal research will become. Yet the nature of legal authority, and the law needed to answer a particular legal question, will remain far less malleable. And that’s what students need to understand. If they understand the issue and what to look for, then they will set out to find it.[46]

B. “Run a Search” Is Not Research[47]

1. Law Students Know How to Gather Information

In general, modern law students are good at digging up bits of information, but they aren’t particularly good at analyzing what they’ve found.[48] Nevertheless, many of them fancy themselves to be experienced researchers.[49] After all, they’ve written many “research” papers. And they do “research” on a daily basis, adeptly using electronic media to grab instant answers to virtually any question they confront. No doubt about it; these folks know how to run a search. But legal research is so much bigger and more sophisticated than most other research they’ve conducted. And, unfortunately, it can be difficult to convince them of this reality.

Consider this example. A while back, I ran into one of my Research & Writing students in the school parking lot. At the time, the class was busy conducting research for that term’s open-memo assignment. I asked him how his research was coming along, and he replied, “It was easy! I think I already have enough cases to write a memo.” Easy? “Enough” cases? He had clearly missed the point.

But, in a way, it was tough to blame him. After all, throughout undergraduate school—and perhaps even during masters’ programs—that’s the mindset: get “enough” sources to write a paper; then write “enough” pages to meet the minimum.[50] Of course, experienced lawyers know that legal research isn’t about getting some finite number of cases. It’s about getting the right legal authorities and—even more fundamentally—it’s about getting the right law. It’s about understanding enough about an unfamiliar issue that one even knows what to look for. Of course, most students come to law school with a very different perspective on “research.” [51] And if we focus our teaching on information-gathering methods, then we may inadvertently feed into the notion that legal research isn’t terribly different from what they’ve been doing for years in other disciplines.

Let’s contrast the overly confident student in the parking lot with another student, who was back on campus after having worked as a summer associate in a large law firm. She revealed that she had no problem transitioning over to LexisNexis after having used only WestlawNext in law school. But she nonetheless felt like a “failure” when it came to legal research. She described the first-year legal research experience as a “nice exercise” (ouch!), but she admitted that, when she received an actual research assignment at the firm, she often didn’t even understand the issue, let alone what she should be looking for to answer it.[52] And, of course, this rendered her ability to gather information on LexisNexis pretty useless.

It is therefore critical to disabuse students of the notion that legal research is easy and familiar—that it’s just a matter of gathering information. [53] To that end, anecdotes like the ones above could be effective, especially when delivered by students or by graduates who’ve been “out there,” experiencing real research first hand. But personal “ah-hah” moments might be even more effective. For example, periodic, pop-quiz-style research simulations might help students to see that they don’t know what they don’t know about legal research.[54] Either way, they need to understand that running searches is a means to an end.

2. Information Gathering Is Only the Beginning

Once students buy into the idea that legal research is different, we can get more specific. Real legal research has two components: locating information and deciding what to do with it. In other words, the legal researcher both gathers and analyzes.[55] Gathering—the part with which students are familiar—is the easy part. But analyzing legal sources is a whole new animal. And that means not only that professors must devote significant time to teaching analysis,[56] but also that students must learn to understand the difference between the two. Consider the following examples:

Most students are quite willing and able to do tasks like the ones in the first column. But will they push on and carefully undertake the critical thinking required by the ones in the second column? Do they understand the difference? To be successful researchers, students must learn to recognize the moment when information gathering ends and the real legal work must begin.

C. With the Right Foundation, Reasoned Research Can Occur in Any Medium

No doubt about it; we are teaching a generation of students who have done no significant research (of any kind) in print.[57] Because other online research seems so easy, they generally underestimate the effort involved in conducting thorough legal research. [58] Consequently, many of them come to law school saddled with a proclivity to demand quick answers and instant gratification.[59] In fact, a good deal of research supports the idea that the Internet is making all of us not just poor researchers, but shallow thinkers and cursory readers as well.[60] This is true not only of the technology “natives,” but also of the immigrants.[61]

Under the circumstances, it’s no surprise that modern students’ legal research proficiency is hindered by what commentators have accurately identified as “shallow reading” and “cut-and-paste” analysis.[62] And there is data aplenty to establish that today’s law graduates are generally inefficient researchers.[63] But is a return to the books the only antidote? In truth, it is unlikely that we’ll beat this characteristic out of law students simply by taking away the tool that makes it easiest for them to manifest it. Instead, they must develop both the mental stamina and the knowledge base to effectively analyze the information that they find.

Traditionally, books provided a concrete framework around which to conduct this analysis. By contrast, the Internet has been aptly described as the world’s largest library with the “books” all over the floor.[64] Of course, this is an alarming vision for those who embrace traditionalist legal research theory.[65] But can “traditional” legal research, that which we associate with orderly libraries and neat shelves of print digests, ever be relevant to the web-native law student? Can it help bridge the gap to deeper legal thinking?

In fact, it can. Despite its print origins, traditionalist legal research theory holds important lessons for the new researcher who is still developing the knowledge base necessary to conduct thoughtful research. Traditionalist legal research theory provides a focused means of organizing information—from general background information to the specific rules that govern a particular legal issue.[66] And organizing and categorizing legal authority are core skills that new researchers desperately need to master.

Therefore, regardless of platform, the “traditionalist” paradigm is grounded in some timeless concepts that can provide a lifeline for novice researchers.[67] First of all, the traditional researcher gains background knowledge in secondary sources, developing a foundational understanding of the topic and identifying terms of art.[68] Second, when searching for case law, the traditional researcher consults legal digests to connect search terms to specific, recognized legal topics.[69] This type of search recruits the aid of more experienced researchers (the publications’ legal editors) to identify the relevant universe of authorities. While keyword searches have a role to play, a topic search helps to define the relevant universe in ways that a keyword search simply cannot. So embracing certain traditional concepts can instill a sense of confidence in the completeness of the results.

And while traditionalist theory was certainly born in the print era, it can come alive in any medium.[70] Today, researchers can conveniently replicate this approach using both free and fee-based electronic sources. Consider the researcher interested in a federal copyright issue. By accessing Nimmer on Copyright on LexisNexis or Patry on Copyright on Westlaw, one could browse the table of contents or launch a word search for direct access to expert commentary and background information. And the attorney researching a state-law issue could find similar success within the state-specific electronic treatises and practice guides.[71]

Even the digests, major players in traditional case law research theory,[72] are available online. Indeed, our hypothetical researchers could use search terms uncovered in the treatises to search Westlaw’s KeySearch or LexisNexis’s Search by Topic. These services replicate the print digests, but with the added convenience of full linking between the topics and the cases that have been classified as containing a relevant headnote within the hierarchy. And, mercifully, they’ve dropped the archaic label—digest—which is beginning to sound dusty and antiquated to professors, never mind to their students.

So, despite arguments to the contrary, the electronic age need not signal the death of the digest concept.[73] It signals, at most, a name change. The value of topic-oriented searching is arguably greater than ever in a library with the books all over the floor (especially when there is no one around who remembers where they were in the first place).[74] As Barbara Bintcliff put it, the topic outlines in the digest system

provide a syndetic structure for each area of law, allowing researchers to understand the relationship, context, and hierarchy of identified rules. To use the digest, you have to think in terms that match its organization; you have to think of rules and hierarchies. The digest’s organization follows the same pattern as our legal reasoning process, and has almost come to be the physical manifestation of “thinking like a lawyer.”[75]

Relationship. Context. Hierarchy. Bintcliff’s words describe concepts that sound anything but outmoded. Of course, there was a time (long ago) when electronic research truly was at odds with traditional views of how legal research should be conducted. First-generation, free-text search logic had nothing to do with the familiar way in which research had been conducted throughout the preceding century. Without the parameters of the West Key Number System and its topical hierarchy, early electronic-search results were at once more precise and more unwieldy.

But today, the disconnect between traditional methods and electronic media has all but disappeared. Lawyers can, and quite frequently do, conduct end-to-end “traditional” research using exclusively electronic sources.[76] Everything the researcher needs—from treatises to digests to recent statutory enactments—is available electronically.[77] Traditional research is very at home on modern platforms. And modern, web-dependent law students need its lessons more than ever.

V. Research in the “Cloud”: A Credible Strategy That Hovers (Without Pointing)

A. A Flexible Framework for a Changing World

To be sustainable beyond the first-year research unit, law students’ understanding of legal research strategy must be based on a credible framework that they actually use.[78] It must also be broad enough to transcend the media in which they will choose to work, both now and in the future. If the proffered strategy feels inefficient or proves unwieldy in practical effect, then they will likely abandon it.[79] And, as noted, if it is anchored directly to today’s technology, then it will probably be out of date by the time they graduate.[80]

Moreover, modern students will better grasp the structure of legal research if the process itself is described as fluid and flexible.[81] Because they did not grow up using books (for legal research, or for anything else), they have no print framework for research to begin with.[82] So, as a threshold matter, it is quite unlikely that they need to “see it first in print” in order to understand the complex web of legal information that they confront electronically.[83] And because they are accustomed to receiving an array of information contemporaneously, a linear model is unlikely to resonate sufficiently that they will internalize it as a valid means of navigating the process.[84] Instead, a broad and flexible paradigm is a better fit.

1. If They Don’t Believe in It, They Probably Won’t Remember It.

Teaching foundational concepts in print is risky business. From the perspective of the digital native, familiarity with print material is no longer essential to understanding the process of legal research.[85] And we lose credibility with many modern law students if we suggest that something of value can only be found in a book.[86]

Worse yet, if we insist on connecting everything back to particular sources or a rigid process, then we may miss the opportunity to truly teach students how to think through a legal problem.[87] For example, if we strive to establish foundational understanding by first teaching the research process in the books, but then we allow students to conduct the actual research for their graded assignments electronically, we create an apparent disconnect. It almost looks as if the organized process belongs to print, while electronic legal research is, by contrast, a free for all.

And if students react to seemingly irrelevant print lessons by failing to internalize foundational concepts, then they will likely revert to old research habits when they inevitably gravitate back to electronic sources to do their actual research.[88] In other words, if the process doesn’t carry over to the media they’re actually willing to use, then they are far less likely to actually learn the fundamental, foundational concepts that are so critical to good legal research.[89] Instead, they may achieve mere “inert” knowledge: “the inability to apply skills and concepts in situations other than those in which they were originally learned.”[90]

On the other hand, when students learn about legal sources as they use them, they are more likely to internalize a non-media-dependent understanding of legal authority and legal analysis. This is the foundation necessary to take with them to wherever technology’s “next big thing” leads. It’s no longer about mechanics. It’s about assuring that the research methods we teach are connected to what the students actually do.

2. When It Comes to Marching Orders, Less Is More

Many volumes of pedagogical scholarship, and many pages of legal research texts, have been devoted to checklists, steps, acronyms, and flowcharts designed to give a sense of direction to the new legal researcher.[91] No doubt, it’s important to have some structure around the daunting task of researching a legal issue. And, of course, most students are happy to cling to templates and checklists.[92] (That way, many of them hope, they can simply plug in their legal problems and wait for the “right answer” to present itself.)

But as professors, we recognize the fine balance between offering models, on the one hand, and helping students to become independent legal thinkers, on the other.[93] An independent legal thinker is capable of tailoring research efforts to meet the specific demands of the project at hand.[94] So the most effective research models are broad and flexible, rather than rigid or detailed.

Flexibility has become even more critical given the rapid evolution of electronic legal research platforms. With even the most traditional electronic-research platforms looking more like Google every day, it is becoming increasingly difficult to force students to march through legal sources in a particular order.[95] In reality, such an approach can feel inconsistent with what is becoming the primary method by which they locate and process information.

As of this writing, traditional Lexis and Westlaw were nearly phased out. So it seems that the Google-esque home screens of Lexis Advance and WestlawNext are the new “normal” when it comes to research platforms (for the time being, anyway).[96] On these new home screens, the researcher enters any old thing into the search box, usually without first identifying a specific database.[97] Then the screen is almost immediately populated with results from a host of sources, both primary and secondary.[98]

So should we tell students to put their blinders on, ignoring relevant items surfaced through invisible algorithms through tools like Westlaw’s ResultsPlus? Wait to look at that information until the “right time”? Run another search later, regardless of the additional expense? This sort of rigidity likely appears wasteful and inefficient to the modern, multi-sensory, multi-tasking millennial. And it probably is wasteful and inefficient in the long run.

Ultimately, the trouble with overly detailed legal research paradigms is that they suggest that legal research is a linear process,[99] when reality often proves this to be untrue. Moreover, most step-by-step approaches require the novice researcher to start the information-gathering process in sources that stand literally no chance of being cited in the written document.[100] Of course, this instruction is quite understandable to the experienced legal researcher, and it is certainly based on sound principles.[101] But the experienced information gatherer can’t help wondering, “But if I go directly to cases, might I not find the perfect case right out of the gate?”

And, if we are honest, don’t we often begin our own research with a case we have stumbled upon, and then “backdoor” into secondary authority as needed to deepen our understanding or gain context? Actual, applied legal research methodology is far more fluid than many teaching models suggest. So when teaching students a framework for understanding legal research, we must be cautious about presenting the process as rigid or template-driven. Students must understand that the steps they will undertake will flex with the circumstances, including the nature of the issue and the amount of information with which they begin. They must understand that precise marching orders are not possible. While they may crave the security of specific commands at the outset, a broader approach will serve them in the long run.[102]

Of course, none of this is to say that students should not follow a strategy. Indeed, a reasoned strategy is a must. But, rather ironically, the more detail we provide, the less intuitive the process may become—and the more quickly it will fail students who encounter a bump in the road. Put simply, when it comes to legal research, a compass is more helpful than a list of turn-by-turn directions.

B. A Tried-and-True Foundation

The paradigm proposed here is familiar in an important way. At its foundation is a research process that stands out for its simplicity and timelessness. First articulated forty years ago by Marjorie Rombauer in her text Legal Problem Solving,[103] this four-step research process was adapted slightly by Joseph Kimble and F. Georgeann Wing for use at Thomas Cooley Law School:[104]

-

Preliminary analysis (or background research)

-

Check for codified law

-

Check for binding precedent

-

Check for persuasive precedent[105]

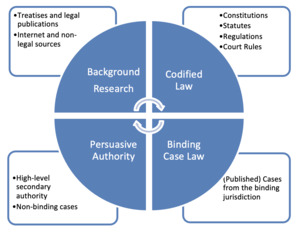

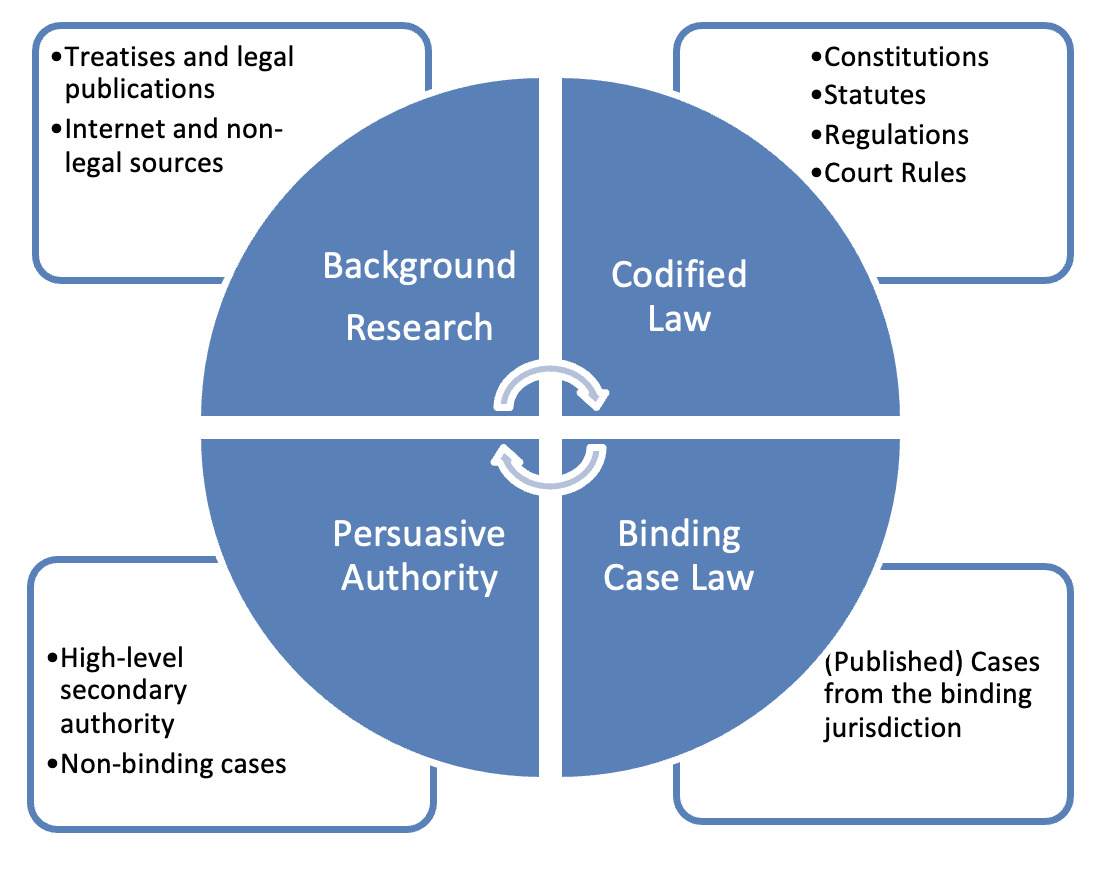

This approach provides an excellent starting point for a modern research strategy, but with another gentle adaptation. Rather than depicting a step-by-step process, the strategy proposed here describes four broad categories, or “buckets,” in which to place the information that the researcher has gathered. The researcher focuses on filling each “bucket” with complete and appropriate information, rather than on following a particular set of steps. So when the linear information-gathering framework is removed from the traditional model, the focus shifts to the important work of categorizing and analyzing legal information.

C. The Cloud[106]-Research Model.

As noted, the task of collecting information isn’t always amenable to sequential ordering, especially in an electronic environment.[107] Even so, recognizing and categorizing legal authority is critically important to legal research—and to sound legal analysis. A legal research strategy focused on categorizing, rather than on sequential gathering, can provide flexible guidance.

Using a category-driven approach, the cloud researcher will build a virtual filing cabinet tailored to the specific research scenario. But instead of checking off steps or sources, the researcher focuses on filling the four categories (the “buckets”) by considering the nature of the information that they have gathered. Drawing on base knowledge about the type of authority needed to address the question,[108] the researcher assesses how “full” (or perhaps overfull) each bucket has become, going out to collect more information as needed. Once the initial information is organized, the researcher can begin the analytic process, ever willing to go back and gather more information if any category is incomplete.

Picture all of this information hovering in a “cloud” above the researcher, who will ultimately pull down relevant items as he or she begins planning and writing the analysis. But this isn’t any old cloud. It’s a virtual filing cabinet. It’s the vehicle for connecting legal research to “cloud computing”—the world’s metaphor for conducting business (and life) in cyberspace.

The researcher’s cloud has four spaces, and each one holds the “bucket” for a particular type of legal information. The researcher will draw from this universe of material, incorporating primary-law authorities into the analysis during the drafting stage. The medium in which the “cloud” is reflected is up to the researcher. For some, it might be a list or chart on a sheet of paper. But, more likely, the cloud’s contents will be reflected in an electronic document with copied-and-pasted material and links to full-text authorities. Or it might reside on Lexis Advance, WestlawNext, or Bloomberg: in the research history, the research folders, or the “sticky” notes. It might even be in a chart on a mobile application like Evernote. But regardless of media, the researcher will organize authorities into the four broad categories and intelligently use them in drafting the legal analysis.

1. The Cloud Researcher in Action

Here is how it plays out in real life. The researcher receives an assignment and follows his or her first instinct, consulting—who else?—Google (the “Great Oz” of the information age).[109] From there, the researcher is clicking away, probably on Wikipedia,[110] lawyers’ websites, and other non-legal sources, like blogs and newsletters. Soon, those sources lead to primary law, including statutes and cases. Those primary-law sources may or may not be up to date, and they may or may not even be from the proper jurisdiction. Nonetheless, together with the non-legal sources, they begin to form the landscape of the initial information-gathering process.

Incidentally, it is important to recognize that, no matter what strategy we put before them, laws students are very likely to begin the process this way. So the model proposed here specifically allows for it but also instructs the researcher to begin putting information into the buckets very early on. To do this effectively, the researcher must have the substantive, foundational knowledge discussed in the preceding sections.[111] And, admittedly, if a student has had less instruction on where to click, then the task of locating information may take a bit of trial and error. But, if that instructional time has been shifted from learning mechanics to understanding authority, as suggested above, then the student will have greater foundational knowledge. And a researcher with such knowledge is far more likely to know what to look for.[112]

The proposed research strategy is depicted in the graphic below, followed by a brief explanation of each category.

Background Materials. Background research can be abundantly helpful to the novice researcher faced with an unfamiliar legal issue. Yet it’s often difficult to get students to linger here. Too often, they want to rush forth on a treasure hunt for the perfect case. Indeed, reading background material can seem like a waste of time when one is in treasure-search mode.[113] And yet we know the truth: the less you know, the less you can usually find, particularly when researching online.[114] But this important category of authority can come to the fore in a non-linear research strategy. Simply put, the researchers can do what they will inevitably do anyway: skip ahead and read some cases. But in doing so, they need not abandon the strategy; this strategy does not dictate which sources to read first.

Of the many things we must teach about this category of authority, a few stand out. First, in terms of categorizing information, students need to accept that non-legal sources like Wikipedia (or quasi-legal sources like lawyers’ websites or professors’ blogs) can be a springboard to research, but the only possible bucket that they can land in is this one. In other words, non-legal sources are a way to find the law; they are not law themselves.

Second, students must learn the importance of context. They must actually believe in the value of gaining a broad understanding of the legal issue before attempting to flesh out the details with more-specific authorities. The professor can help to instill this belief by demonstrating the value of expert commentary in class. For example, the professor could use an in-class exercise to show how much easier it is to navigate an unfamiliar area of law with a good secondary source than with a list of cases.

Finally, students must understand that all secondary sources are not created equal. This bucket will contain two types of information: (1) finding aids and (2) true secondary legal authority. New researchers must develop a habit of critically assessing the sources of their background information. For example, an open-web search will yield mostly finding aids: sources that lead to legal authority, but which are not credible enough to be authority on their own. On the other hand, a treatise or a law-review article is secondary authority; researchers can use the information to develop context and understanding. They could even cite these authorities to a court. This bucket is not properly filled until the researcher has a sense of context for legal issue—context that is based on credible authority.

Codified Law. This category emphasizes the primacy of enacted law in legal analysis. Too often, the research experience in first-year classes has the unintended consequence of downplaying the importance of a comprehensive statutory search. Professors often want to assure that students have the correct codified law before they go too far in writing the analysis. So we might discuss “the statute” in class, or we might point students toward it during conferences or question-and-answer sessions. When this happens, students may come away with the impression that finding codified law is pretty easy and that the real work is the treasure hunt for the perfect cases to include in the memo. Consequently, they are often eager to leap past this step and get to what they “really need”: the cases. Of course, this mentality impedes internalizing a proper understanding of the importance of codified law.

But in a carefully designed research unit, students should have opportunities to practice recognizing and analyzing codified law. Through this process, they will learn to recognize codified law when they see it, and will instinctively place any such information into this bucket, even if they have read cases before thoroughly searching for enacted law. When it comes time to assure that this bucket is properly filled, the researcher will check to see that the items here are both current and from the binding jurisdiction. The researcher might also need to assess which of the many items in this bucket actually govern the legal issue. Finally, they must assure that there aren’t additional sources of governing law, such as regulations or procedural rules. After identifying the codified items that are current, complete, binding, and relevant, the researcher should discard the rest.

Binding Case Law. This bucket will house a group of potentially relevant cases. Undoubtedly, the researcher will have unearthed some relevant cases while sifting through other sources. Thus, they will have information to drop into this category very early on. But when assessing the contents of this category, the researcher should initially begin sorting cases based on whether they are binding in the jurisdiction. All other cases should be moved to the persuasive authority category. This will help the researcher to focus first on articulating the main rules before considering nuances or novel arguments.

The second critical step is to use a reasoned approach to both (1) define the relevant universe (cases that belong in the bucket because they are generally on point) and (2) narrow to the most factually analogous cases (cases that will most likely make their way into the written analysis). To do this, the researcher should use a combination of topic-based (digest-style) and keyword (free-text) search methods. The topic search helps to ensure that the researcher has uncovered the broad, general rules and the current state of the law. And the keyword search can help to identify specific cases with similar facts or important nuances.

Many novice researchers are attracted to keyword searches, which seem like the most direct way to get to that “perfect” case. And, indeed, once the researcher has context, this type of search allows excellent control over the search results. But in an unfamiliar area of law, the topic-based search offers some important advantages. First, the topic-based search limits the results to cases the legal editors have identified as generally relevant to the topic. Second, the topic-based search reduces the chances of missing a key authority. When used together, the two search methods assure that the researcher can both articulate the broad, general rules and identify the most relevant authorities to use as illustrations or examples.

Persuasive Authority: This is the place to house any non-binding cases or any high-level secondary authority that the researcher turns up along the way. Although many assignments will not warrant additional research in this area, it is important to include this category so that the researcher develops a habit of thinking critically about the state of the law in the relevant jurisdiction. And if an exhaustive search of binding authority leaves an important question unanswered, then the researcher can draw upon persuasive cases and high-level secondary authority to craft an argument.

After assessing the contents of each bucket, the researcher can feel confident that the gathering process is complete. This will be true regardless of the order (or the media) used to gather the information.

2. The Research Cloud and the Writing Process

As the cloud’s buckets become even partially filled, the researcher can begin planning the written analysis. The sooner one begins planning and writing, the sooner any “gaps” or other research deficiencies will present themselves. Thus, this approach fuses research and writing in a credible way. After creating a preliminary universe of “candidates” for inclusion in the piece, the researcher stops fretting about when to stop gathering tidbits of information. Instead, they begin drafting early on, using that process as a means of synthesizing the law, identifying the best authorities, and exposing any deficiencies in the research. So the research is never “done” before the memo is. And the memo writing starts before the research is necessarily complete.

To assure that students effectively connect the research and the writing in this way, professors should incorporate pre-writing tools that probe students to reflect critically on the information gathered, as well as to assess the potential need for more. Reflective assessment has long been recognized as a critical tool for legal research instruction,[115] and its value in a non-linear research process cannot be overstated.

An effective pre-writing model would be to require both a research log and an attack outline. The log[116] would reflect the main authorities included in each area of the research cloud. In essence, it would be a summary of the cloud’s most-critical content.[117] The attack outline[118] would provide a concrete means of connecting this content to the written analysis. As the researcher addresses the various elements of the outline, he or she should be able to pull down necessary authority from the cloud, as manifested in the log. If they cannot, then more research is likely warranted.

VI. Conclusion

We must look at legal research with fresh eyes in order to effectively teach this critical skill to modern law students. It is becoming increasingly clear that students need more exposure to fundamental legal concepts than they do to platforms and mechanics. A flexible, non-linear approach is more relevant to modern law students than the more-rigid paradigms of the past. If students become efficient at intelligently organizing information around the four broad categories described here, then they will have both the solid foundation and the flexibility to conduct effective research in the real world.

Job Access with Speech (JAWS) is a software program designed for visually impaired PC users that reads aloud computer screen content. Freedom Scientific, JAWS for Windows Screen Reading Software, http://www.freedomscientific.com/products/fs/JAWS-product-page.asp (accessed Nov. 1, 2014).

The faculty and staff responsible for teaching legal research vary from law school to law school. Excellent research instruction is conducted by full-time faculty, clinical professors, legal-writing professors, law librarians, and other legal professionals. Thus, the titles “professor,” “teacher,” and “instructor” are used interchangeably here.

As younger professors continue to join our ranks, this may not be true of all professors responsible for teaching research. But it is nevertheless true of many of us.

With a solid research foundation, students will typically have more time to confidently focus on good writing and analysis. See Sarah Valentine, Legal Research as a Fundamental Skill: A Lifeboat for Students and Law Schools, 39 U. Balt. L. Rev. 173, 188–189 (2010).

See Carrie W. Teitcher, Rebooting the Approach to Teaching Research: Embracing the Computer Age, 99 L. Lib. J. 555, 555–556 (2007) (noting that students may “writ[e] us off as relics” if we emphasize book research).

See Ian Gallacher, Forty-Two: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Teaching Legal Research to the Google Generation, 39 Akron L. Rev. 151, 164 (2006) (noting that law students typically have used computer technology to achieve high levels of academic success).

See Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 555–556.

Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 164 (footnote omitted).

Suzanne Ehrenberg & Kari Aamot, Integrating Print and Online Research Training: A Guide for the Wary, 15 Persps. 119, 119 (Winter 2007) (The “bridge” generation “grew up on print, with indexes and tables of contents as our tools . . . [t]hen, somewhere along the way, . . . learned the computer.”).

A “digital native” is a “‘native speaker’ of the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet.” Marc Prensky, Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, 9 On the Horizon 1, 1 (Sept.–Oct. 2001).

For an explanation of the “data smog” concept, see generally David Shenk, Data Smog: Surviving the Information Glut (1st ed., Harper Edge 1997) (examining the effects of the overwhelming amount of information available on the Internet).

Released by LexisNexis in 2011, Lexis Advance is the company’s next-generation online legal research platform. It features a “Google-like” search bar that allows the researcher to search across all libraries simultaneously. LexisNexis, Lexis Advance, http://www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/products/lexis-advance.page (accessed Jan. 5, 2015).

Powered by Google, Google Scholar is a search engine that allows the researcher to search for scholarly literature across a variety of disciplines. Google, Google Scholar, http://scholar.google.com/ (accessed Jan. 5, 2015).

“The Oyez Project at Chicago-Kent is a multimedia archive devoted to the Supreme Court of the United States and its works. It aims to be a complete and authoritative source for all audio recorded in the Court since the installation of a recording system in October 1955.” Oyez, About Oyez, http://www.oyez.org/ (accessed Jan. 5, 2015).

“Justia provides Internet users with free case law, codes, regulations, legal articles and legal blog and twitter databases, as well as additional community resources.” Justia Virtual Chase, Legal Portals and Pathfinders, http://virtualchase.justia.com/wiki/legal-portals-and-pathfinders (accessed Jan. 5, 2014).

See e.g. Simplifying Legal Research: Thomson Reuters Rolls Out WestlawNext at Legaltech, 27 Law.'s PC 1 (Feb. 15, 2010) (“[WestlawNext] is designed with a clean, modern interface and powerful new search functionality intended to make legal professionals more efficient. It also gives them the confidence that they’ve explored every relevant document in a search.”); Thomson Reuters, Advertisement, 91 Mich. B.J. 12, 13 (Dec. 2012).

See e.g. Paul D. Callister, Beyond Training: Law Librarianship’s Quest for the Pedagogy of Legal Research Education, 95 L. Lib. J. 7, 9–11 (2003) (providing historical perspective on the pervasive deficit in law graduates’ research skills); Valentine, supra n. 4, at 173–174 (noting that “[b]eyond laments about the lack of general lawyering skills, the bench and bar also routinely highlight the inadequacy of the legal research skills of recent law graduates” (footnote omitted)).

Id.

See generally ABA Sec. Leg. Educ. & Admis. to B., Legal Education and Professional Development—An Educational Continuum, Report of the Task Force on Law Schools and the Profession: Narrowing the Gap 157 (ABA 1992) [hereinafter MacCrate Report].

See infra sec. IV(B)(2).

See MacCrate Report, supra n. 19, at 157.

William M. Sullivan et al., Educating Lawyers: Preparation for the Profession of Law (Jossey-Bass 2007) [hereinafter Carnegie Report].

The Carnegie Report has generated both criticism and praise. See generally Lisa T. McElroy et al., The Carnegie Report and Legal Writing: Does the Report Go Far Enough? 17 Leg. Writing 279 (2011). Although the report applauds certain aspects of legal education, it also criticizes perceived deficiencies in practice-oriented training:

Most law schools give only casual attention to teaching students how to use legal thinking in the complexity of actual law practice. Unlike other professional education, most notably medical school, legal education typically pays relatively little attention to direct training in professional practice. The result is to prolong and reinforce the habits of thinking like a student rather than an apprentice practitioner, conveying the impression that lawyers are more like competitive scholars than attorneys engaged with the problems of clients.

Carnegie Report, supra n. 22, at 188; see also Mark F. Kightlinger, Two and a Half Ethical Theories: Re-Examining the Foundations of the Carnegie Report, 39 Ohio N. U. L. Rev. 113, 113 (2012) (“In the past three years, the American Bar Association, several major state bar associations, the Association of American Law Schools, the New York Times, law students, and many legal educators have called for fundamental changes in the way we educate new lawyers.”).

See e.g. Callister, supra n. 17, at 38–40 (examining the use of primary, secondary, and combined legal sources in legal research); Marjorie C. Rombauer, Legal Problem Solving: Analysis, Research and Writing 134–145 (West 1983) (offering a framework of steps for legal research); Valentine, supra n. 4, at 207–208 (discussing the components of legal research). On the other hand, some have argued that instruction on the mechanics of information gathering is still essential to mastery of the legal research process. See e.g. Matthew C. Cordon, Task Mastery in Legal Research Instruction, 103 L. Lib. J. 395, 405 (2011).

The bibliographic approach emphasizes understanding and categorizing legal sources, while the process-oriented approach emphasizes frameworks for approaching a legal research problem. See Callister, supra n. 17, at 8–21 (examining the debate between the “process-oriented” approach and the “bibliographic” approach).

Am. Assn. of L. Libs. (AALL), Principles and Standards for Legal Research Competency 1–2 (approved by the Exec. Bd. July 11, 2013) (available at http://www.aallnet.org/Documents/Leadership-Governance/Policies/policy-legalrescompetency.pdf) (providing “Principle I: A successful legal researcher should possess fundamental knowledge of the legal system and legal information sources. Principle II: A successful legal researcher gathers information through effective and efficient research strategies. Principle III: A successful legal researcher critically evaluates information. Principle IV: A successful legal researcher apples information effectively to resolve a specific issue or need. Principle V: A successful legal researcher distinguishes between ethical and unethical uses of information, and understands the legal issues associated with the discovery, use, or application of information.”).

See e.g. Margaret Butler, Resource-Based Learning and Course Design: A Brief Theoretical Overview and Practical Suggestions, 104 L. Lib. J. 219 (2012) (suggesting a “problem-based approach” to teaching legal research); Vicenc Feliu & Helen Frazer, Embedded Librarians: Teaching Legal Research as a Lawyering Skill, 61 J. Leg. Educ. 540 (2012) (examining ways to better utilize librarians in law school courses).

See e.g. Joseph Kimble, I’m Ready: Learning Research and Reasoning through Audiotapes, 3 Trends L. Lib. Mgt. & Tech. 1, 1 (1990) (outlining a four-step legal research process adapted from Marjorie Rombauer, Legal Problem Solving: (1) perform background research, (2) check for codified law, (3) check for binding precedent, (4) check for persuasive precedent); Rombauer, supra n. 24, at 134–136 (describing four steps in the research process: (1) search for statute or other written law, (2) search for mandatory precedents, (3) search for persuasive precedents, (4) search for refinement of the researcher’s analysis).

See e.g. Rombauer, supra n. 24, at 134–145.

See Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 565 (referring to students as “expert finders” rather than “thinkers”).

Julie M. Jones, Not Just Key Numbers and Keywords Anymore: How User Interface Design Affects Legal Research, 101 L. Lib. J. 7, 10 (2009) (quoting Herbert Simon, Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World, in Martin Greenberger, Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest 37, 40–41 (John Hopkins Press 1971)) (“Where information is abundant, as it is for law students, access to more information is not the problem. Rather, the problem is the efficient allocation of attention to the right information: ‘What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.’”).

Kevin P. Brady & Justin M. Bathon, Education Law in a Digital Age: The Growing Impact of the Open Access Legal Movement, 277 Ed. L. Rep. 589 (2012).

For example, on WestlawNext, when the researcher merely enters a case name and jurisdiction on the home screen, it’s not terribly difficult to locate the case on the resulting list.

See e.g. WestlawNext, Getting Started with Online Research, http://lscontent.westlaw.com/images/content/WLNGettingStarted10.pdf (June 2010).

Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 565.

Ehrenberg & Aamot, supra n. 9.

See Larry Sanger, How the Internet Is Changing What We (Think We) Know, http://larrysanger.org/2008/01/how-the-internet-is-changing-what-we-think-we-know/ (Jan. 23, 2008) (criticizing the manner in which the surplus of information available on the Internet had devalued the quest for knowledge).

Ronald E. Wheeler, Does WestlawNext Really Change Everything? The Implications of WestlawNext on Legal Research, 103 L. Lib. J. 359, 373–375 (2011) (evaluating WestlawNext one year after its release).

See e.g. Westlaw Insider, WestlawNext: Filtering Case Results, http://www.youtube.com/v/5liaOyRyRbI?version=3&f=playlists&app=youtube_gdata (accessed Oct. 27, 2014) (depicting Westlaw’s case-law search-results screen).

See Valentine, supra n. 4, at 188–190 (explaining that the proliferation of easily accessed information has actually made it more difficult to locate what is truly useful).

This concept is recognized in AALL’s information literacy report. See AALL, supra n. 26.

For example, WestlawNext and Lexis Advance had yet to be released when the May 2012 law graduates entered law school. It is unlikely that those graduates are using the mechanics of the old interfaces in their current legal work.

See e.g. Brooke J. Bowman, Researching Across the Curriculum: The Road Must Continue Beyond the First Year, 61 Okla. L. Rev. 503, 551 (2008) (emphasizing that repetition is crucial to retention of legal research skills); Ehrenberg & Aamot, supra n. 9.

The “flipped” classroom offers many pedagogical benefits. See Dan Berrett, How “Flipping” the Classroom Can Improve Traditional Lecture, Chron. of Higher Educ. (Feb. 18, 2012) (available at http://chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857/).

Callister, supra n. 17, at 10.

Theodore A. Potter, A New Twist on an Old Plot: Legal Research Is a Strategy, Not a Format, 92 L. Lib. J. 287, 288 (2000) (noting that if students are able to assess the nature of the legal issue, then their legal research will be more effective).

See Kristen Purcell et al., How Teens Do Research in the Digital World, http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_TeacherSurveyReportWithMethodology110112.pdf (Nov. 1, 2012) (reporting the results of a study that reveals how the Internet has impacted students’ research skills).

See e.g. Potter, supra n. 46, at 291 (noting that “[o]nce students have printed all of the documents with the words of their searches in them, the research process stops.”); Valentine, supra n. 4, at 189 (citing Thomas Keefe, Teaching Legal Research from the Inside Out, 97 L. Lib. J. 117, 119 (2005)) (noting that “the concept of a conscious, thoughtful, articulable research process has been disrupted by the ease of typing one or two words into a search engine and being rewarded with pages of results”).

See Blair Kauffman, Information Literacy in Law: Starting Points for Improving Legal Research Competencies, 38 Intl. J. Leg. Info. 339, 345 (2010) (“The current born digital generation of students how entering law school may have a false sense of competence in their legal research skills stemming from their use [sic] seemingly simple search engines such as Google, and pulling information from sources found on their first one or two pages of search results, such as Wikipedia.” (Footnotes omitted)).

See Jones, supra n. 31, at 8 (noting that law students’ affinity for, and familiarity with, keyword searching often leads them to “[rely] upon the ‘good enough’ sources freely available on the Internet”).

Potter, supra n. 46, at 291.

Unfortunately, this experience is not uncommon. Many novice researchers haven’t confronted sufficient “ill-defined” research issues to confidently address one. See Kristin B. Gerdy, Teacher, Coach, Cheerleader, and Judge: Promoting Learning through Learner-Centered Assessment, 94 L. Lib. J. 59, 66–68 (2002).

See Potter, supra n. 46, at 291 (noting the difference between research strategies of past students (who “had to write notes in longhand to properly attribute the ideas and words they found in the library materials”) and research strategies of today’s students (who have unlimited printing and whose search is “limited to what their inexpert search strategy produces and to what they print”)).

For a good source of practice exercises, see Cassandra L. Hill & Katherine T. Vukadin, Legal Analysis: 100 Exercises for Mastery, Practice for Every Law Student (LexisNexis 2012).

These two aspects of the legal research process directly coincide with principles II and III of the AALL information-literacy standards: Principle II: “A successful legal researcher gathers information through effective and efficient research strategies,” and Principle III: “A successful legal researcher critically evaluates information.” AALL, supra n. 26, at 1.

See Callister, supra n. 17, at 33–40 (discussing analytical frameworks for research training); Cordon, supra n. 24 at 405 (noting that “finding documents is rather pointless if the researcher is unable to use the documents”); Rombauer, supra n. 24, at 134–145.

See Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 555.

See Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 167 (stating that “‘[t]he Internet has made it so easy to find information that students often do not know how to search for it’” (quoting Keefe, supra n. 48, at 122).

Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 555.

See generally Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (W. W. Norton & Co. 2010).

Id.

Spencer L. Simons, Navigating through the Fog: Teaching Legal Research and Writing Students to Master Indeterminacy through Structure and Process, 56 J. Leg. Educ. 356, 365 (2006) (citing Molly Warner Lien, Technocentrism and the Soul of the Common Law Lawyer, 48 Am. U. L. Rev. 85, 88 (1998)).

See e.g. Feliu & Frazer, supra n. 27, at 550; Valentine, supra n. 4, at 174.

John Allen Paulos said, “The Internet is the world’s largest library. It’s just that all the books are on the floor.” Quote Garden, Quotations about the Internet, http://www.quotegarden.com/internet.html (last updated Oct. 29, 2014, 21:08 PDT).

See Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 160 (“The traditionalist view of legal research has, at its core, the firm conviction that book-based legal research is superior to electronic research, at least as a first step in almost any research project.”).

Id. at 161–162.

Id. at 162–163.

Id. at 161–162.

Id.

See Ehrenberg & Aamot, supra n. 9, at 119 (noting that “[a]s online databases become more complete and can be searched in multiple ways, including by index, by key number, and by tables of contents, book research offers little that cannot be replicated online”).

For example, on WestlawNext in “State Materials,” and on Lexis Advance in “States Legal—U.S.” For an example of a state-specific practice guide, see the Michigan ICLE website, available at https://www.icle.org.

See Barbara Bintliff, From Creativity to Computerese: Thinking Like a Lawyer in the Computer Age, 88 L. Lib. J. 338, 341 (1996) (“For well over a hundred years, our ‘thinking like a lawyer’ skills have been shaped by—and some would argue even determined by—the simple device of the case digest.”).

The debate about the death of digests is beyond the scope of this article. But many have observed that the ability to conduct research outside the parameters of the West system threatens to unravel traditional concepts of precedent. See e.g. Ellie Margolis, Authority Without Borders: The World Wide Web and the Delegalization of Law, 41 Seton Hall L. Rev. 909, 911 (2011) (noting that the primacy of “traditional” legal authority “is beginning to weaken and that, increasingly, nontraditional sources are being used to support legal analysis”); William R. Mills, The Decline and Fall of the Dominant Paradigm: Trustworthiness of Case Reports in the Digital Age, 53 N.Y. L. Sch. L. Rev. 917, 919–922 (2008–2009) (arguing that electronic research is eroding the impact of the West key-number system); Lee F. Peoples, The Death of the Digest and the Pitfalls of Electronic Research: What Is the Modern Legal Researcher to Do? 97 L. Lib. J. 661 (2005) (generally describing philosophical debate about the impact of the Internet on the American common-law system); Valentine, supra n. 4, at 193 (arguing that electronic research has “affected the very structure of the law as it has been understood and taught for more than a century”). Valentine even noted that,

[t]he very act of accessing the law electronically restructures the law. It erodes the idea that one can learn the law from the scientific study of readily agreed upon precedent. As the historical understanding of law shifts, the ability to teach students to think like lawyers using the structured concepts of the legal system developed by Langdell and West begins to collapse.

Valentine, supra n. 4, at 195.

Supra n. 64.

Bintliff, supra n. 72, at 343.

See e.g. Sanford N. Greenberg, Legal Research Training: Preparing Students for a Rapidly Changing Research Environment, 13 Leg. Writing 241, 246–250 (2007) (summarizing results of a 2005 survey in which attorney-respondents “overwhelmingly” reported their tendency to conduct research online, rather than in print).

Ehrenberg & Aamot, supra n. 9, at 119; Gallacher, supra n. 6, at n. 51 (Online legal databases now “have extensive secondary source databases that allow electronic researchers to conduct the same ‘secondary source first, primary source second’ research model as that advocated by paper researchers.”).

Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 556–557.

Id.

Id.; see also supra n. 42 and accompanying text (discussing rapid changes in research mechanics).

See Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 201.

See id. at 167 (noting that law students who are “irretrievably married to computers as their primary research tool” lack the background necessary to understand current legal research teaching).

Id. at 201–202.

But see Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 567 (recognizing that students are attracted to electronic sources that allow them to jump from one concept to another, but arguing that, as of 2007, books still played an important role in establishing context).

See e.g. Greenberg, supra n. 76, at 242.

See Teitcher, supra n. 5.

Potter, supra n. 46, at 290.

See Valentine, supra n. 4, at 175 (noting that the disconnect between teaching methods and actual electronic research “places the first-year law student in a situation where how she is taught legal analysis and reasoning does not comport with what she finds when she researches the law herself”).

See Bowman, supra n. 43, at 551 (noting that repetition and making mistakes reinforces research skills); Gerdy, supra n. 52, at 66 (noting that ineffective legal research instruction can create “‘inert’ knowledge—the inability to apply skills and concepts in situations other than those in which they were originally learned” (footnote omitted)).

Gerdy, supra n. 52, at 66.

See generally Feliu & Frazer, supra n. 27, at 547–550 (reviewing several legal research titles that present a variety of paradigms and processes).

But while students welcome forms and templates, they must use them with great caution. Terry Jean Seligmann, Why Is a Legal Memorandum Like an Onion?—A Student’s Guide to Reviewing and Editing, 56 Mercer L. Rev. 729, 730–731 (2005) (“Any guideline or checklist should not be viewed as setting up rules applicable to all situations, or formulas that must be slavishly followed whether or not the legal analysis for the case fits the formula.”).

See Kristin B. Gerdy et al., Expanding Our Classroom Walls: Enhancing Teaching and Learning through Technology, 11 Leg. Writing 263, 278 (2005) (describing a database of sample memoranda as an instructional resource used for teaching legal research).

See Terry Jean Seligmann, Beyond “Bingo!”: Educating Legal Researchers as Problem Solvers, 26 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 179, 183 (2000) (“Qualities characterizing an accomplished legal researcher might include competence, accuracy, judgment, thoroughness, efficiency, confidence and knowledge.”).

Michael L. Rustad & Diane D’Angelo, The Path of Internet Law: An Annotated Guide to Legal Landmarks, 2011 Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 12, 93.

Wheeler, supra n. 38, at 360.

WestlawNext, Welcome to WestlawNext, https://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/wln2/L-356012.pdf (accessed Jan. 28, 2015).

Wheeler, supra n. 38, at 361.

This could be inadvertent, but that is still how students see it.

Although students cite mostly primary law in their legal memoranda, most research paradigms appropriately suggest that the researcher begin with background research in secondary sources. See e.g. Kimble, supra n. 28, at 1.

See Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 161–62 (referring to secondary resources as the first step in a linear research process); Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 556–557.

This is particularly true of millennials, who often exhibit contradictory characteristics: a desire for freedom to use the media of their choice paired with a desire for specific directions guaranteed to produce the desired grade. See Aliza B. Kaplan & Kathleen Darvil, Think (and Practice) Like a Lawyer: Legal Research for the New Millennials, 8 JALWD 153, 175 (2011) (“[Millennials] want freedom and flexibility, but they also want rules and responsibilities to be spelled out explicitly. They want to play by the rules, but there is a hesitancy to think outside the box.”).

Feliu & Frazer, supra n. 27, at 548. Vicenç Feliú & Helen Frazer recently explained and praised Rombauer’s work:

The methodology and underlying pedagogy of Rombauer’s process approach to legal research instruction are similar to those advocated in the Carnegie Report. Students are introduced to model documents characteristic of professional trial practice. They are coached in how to analyze law, perform research and produce similar legal documents. Concepts are reiterated with every assignment as students move from simple case briefs for classroom preparation through analysis of a published casenote and preparation of trial and appellate documents. In other words, the Rombauer method and its progeny appear to anticipate the pedagogical techniques advocated in the Carnegie Report, including modeling, coaching, scaffolding, and fading. Rombauer’s course book includes the most detailed and sophisticated presentation of legal analysis from precedent necessary to perform research at the professional level of practicing attorneys. It is not a book or method widely used in first year legal research and writing programs, although Rombauer’s influence is detectable in the nods to process in current research and writing texts and manuals . . . .

Id.

Since the 1990s, Cooley has been teaching legal research using a hands-on approach founded on Rombauer’s four steps. Kimble, supra n. 28, at 1.

Id.

The phrase “cloud computing” typically refers to storing and accessing information away from the confines of a computer hard drive. See Eric Griffin, What Is Cloud Commuting? PCMag.com, http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2372163,00.asp (Mar. 13, 2013).

Rustard & D’Angelo, supra n. 95; Teitcher, supra n. 5. at 556–557.

Rustard & D’Angelo, supra n. 95; Teitcher, supra n. 5, at 556–557.

See Alena Wolotira, Googling the Law: Apprising Students of the Benefits and Flaws of Google as a Legal Research Tool, 21 Persps. 33 (Fall 2012) (“[S]tudents are likely to start the process of legal research with Google because it is what they know, it is fast and easy, and it sometimes does yield usable results.”) (available at http://info.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/pdf/perspec/2012-fall/2012-fall-7.pdf).

Wikipedia may be accessed at http://www.wikipedia.org/.

Supra nn. 32–56 and accompanying text.

Supra nn. 32–56 and accompanying text.

See Seligmann, supra n. 94, at 190–191.

See Gallacher, supra n. 6, at 183.

See e.g. Gerdy supra n. 52, at 71 (advocating for a reflective process of assessing students’ work during legal research projects).

See app. A.

Professor Bradley Charles’s Research Plog is designed to serve as both a planning tool and a record of research results. It incorporates the same categories (buckets) as the cloud-research model proposed in this Article. However, the terms “Binding Case Law” and “Persuasive Authority” are used here to better reflect the content of this article. For the original Plog and a detailed explanation of its role in the research process, see Professor Charles’ electronic text, Reasoned Legal Research, and Bradley J. Charles, Toree Randall, and Erika Bretfeld’s text, Reasoned Legal Research (available on SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2364984 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2364984).

See app. B.