Introduction

In early October 2022, the Supreme Court began a term rife with important cases. Among those cases was Allen v. Milligan (formerly Merrill v. Milligan), the Alabama redistricting case that many commentators believed would represent the end of Voting Rights Act protections regarding racial gerrymandering cases.[1] These predictions seemed very reasonable, especially given that the Supreme Court had allowed the redistricting plan to go into effect.[2] At this same time, we publicly noted that consideration of the quantitative features of the party and amicus briefs regarding the merits of the cases indicated an advantage to preserving these voting protections and shaping the opinion’s content accordingly.[3] Specifically, the number and length of the briefs arguing there was a violation of the Voting Rights Act, the consistently similar language used in those briefs, and the involvement of experienced attorneys favored the Respondent.[4] Based on our prior research, we believed all of these factors helped predict that “observers might be surprised by this highly conservative court deciding Merrill that Alabama has indeed violated the Voting Rights Act.”[5] On June 8, 2023, the Supreme Court decided that Alabama had violated the Voting Rights Act.[6] Journalists and commentators described the decision as a “surprise”[7] and “surprising,”[8] a “shock”[9] and “shocking,”[10] a “curveball,”[11] and “unexpected.”[12] Yet our empirical analysis of thousands of briefs led us to anticipate just such an outcome.

There is a growing body of studies using statistical and text-analytic approaches to consider the influence of briefs in litigation.[13] Why care about these quantitative studies? They allow for rigorous testing of relationships that we think might exist, allowing us to move beyond received wisdom and hunches.[14] In this Article, we consider what we can learn from social science research regarding briefing, including from research we conducted. Our investigation centers on elements that an attorney can shape and others that are more out of an advocate’s control. While our primary focus will be on briefing the Supreme Court of the United States, in keeping with existing studies, we will also discuss studies that consider other federal courts and some state courts. We highlight how the research confirms conventional wisdom and challenges it. Additionally, we offer new quantitative analyses regarding the maximum cumulative impact controllable factors can have in Supreme Court litigation and which individual factors advocates can take too far, potentially reducing their impact on how the case is resolved. We then conclude the Article by highlighting what social science research generally, and ours specifically, can help you learn about briefing.

I. An Overview of Social Science Research on Briefing

A. Types of Studies

Studies regarding legal briefs come from multiple fields, including law and political science.[15] Additionally, studies cover both party and amicus briefs, though often separately.[16] Most studies focus on the Supreme Court, likely because it is the most powerful court in the country, but also due to the ease of accessing the relevant documents and the more manageable size of the corpus. The focus on the Supreme Court is especially pronounced in research regarding amicus briefs,[17] likely due to the unique role such briefs play in judicial decision making at the Court.[18] It is also unsurprising that studies regarding the role of information, including reasons and principles, often focus on the Supreme Court, as those elements are particularly important in that arena.[19] However, scholars have analyzed briefs in other courts at both the federal and state levels.[20] Our primary focus in this Article is on Supreme Court litigation. Still, we also refer to these other studies, which generally speak to aspects of briefing and are of interest to many attorneys who practice outside of the Supreme Court.

These studies also vary in their focus.[21] For purposes of this guide on what social science can teach us about briefing, we provide a typology centered on factors that attorneys can and cannot control. Regarding more controllable elements, scholars have studied issues of coordination in terms of how many other parties and amici you want at the table,[22] as well as their experience[23] and relationships to the specific issue.[24] Second, social scientists have considered what features of a brief lead to more advantageous results regarding aspects of writing, the types and quantity of information included, strategic approaches, and the use of policy-oriented language.[25] Next, we address the body of evidence regarding the influence of factors an attorney can’t control, such as the ideological predisposition of the justices, along with some potential ways to ameliorate a bad hand. After discussing this wide range of individual factors, we present original research that assesses the maximum cumulative effect controllable and uncontrollable factors can have in Supreme Court litigation. We also go beyond existing empirical scholarship to explore which controllable factors pose a danger of an advocate going too far.

B. Quantitative Approaches to Studying Briefing

When social scientists study briefing, they use a wide range of empirical approaches, including qualitative methods, such as interviews and content analysis that doesn’t employ numerical methods, and quantitative methods, such as numeric-based computational text analysis and statistical means.[26] In this Article, we focus on quantitative approaches, though qualitative studies can also be quite informative. We chose to concentrate on quantitative studies because they provide clear estimates of effects even while accounting for multiple factors, allow for rigorous assessment of the precision of the estimates, and have predetermined standards for how certain estimates must be in order to be considered significant.

In assessing aspects of briefing, quantitative studies tend to use types of multiple regression analysis to evaluate the influence of key explanatory factors on an outcome of interest, such as who wins a case or the similarity between briefs and opinions.[27] Such methods allow researchers to estimate specific factors’ effects while holding other potentially influential elements constant.[28] Furthermore, scholars use computational text analytic tools in many studies to study the effect of the writing in briefs and opinions. These researchers often use software applications, such as Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC),[29] to assess the linguistic features of the writing, including measuring how much of the language has certain grammatical features, such as part of speech or tense, or relates to specific concepts, such as emotionality, causation, and certainty.[30] These measures help scholars consider the influence of various aspects of the writings while also being able to conduct rigorous statistical analysis.[31] Furthermore, citations represent a specialized type of language and communication in legal writing.[32] Scholars can research them to analyze connections between ideas and doctrine across documents.[33]

Additionally, scholars use different tools to consider how writings are connected, including the use of plagiarism software[34] and text analytic tools for assessing similarities across texts, even where there is not identical or nearly identical phrasing, such as tf-idf and cosine similarity.[35] Such techniques can be applied to citations in addition to the texts at large.[36] Such approaches allow for rigorous and transparent analysis of the relationships between documents.[37] Such approaches help us learn about the effectiveness of briefing because they act as indicators of influence: where an opinion more closely resembles a brief, it is more likely to represent the statements of fact and applications of law sought by the briefing party. Thus, it helps us assess features in briefs that make for more influential filings. In this Article, we highlight many empirical social science studies, including our book, in which we used text analytic tools to analyze over twenty-six thousand merit briefs, from both parties and amici, filed in the Supreme Court between 1984 and 2015, along with the text of the relevant lower court and Supreme Court opinions.[38]

II. Aspects of Briefing Attorneys Can Control

The most apparent benefit social science research can provide for practicing attorneys is the light it sheds on factors that they can directly manipulate. Empirical findings regarding what influences a court can enhance the knowledge counsel gain through traditional educational and experiential sources. Although advocates can gain crucial insights through their own observations, social science can reveal patterns only evident when looking at a much larger quantity of data. Understanding those patterns can enable counsel to better persuade a court by knowing the most effective way to present information.

A. Coordination, Coordination, Coordination! Who You Want at the Table

No brief is an island unto itself. In an adversarial legal system like that of the United States, attorneys draft a brief on any issue at virtually any court level in anticipation of, and response to, opposition arguments.[39] However, the interconnected nature of briefs is especially important in Supreme Court litigation, where extensive amicus briefing has long been the norm.[40] As a result, drafting a brief involves not only addressing opposition arguments but also coordinating with other briefers who want the same (or similar) result.[41] High-profile Supreme Court litigators understand the importance of curating the information presented.[42] There are limits to how much attorneys can control this, both because amici can file without the consent of the parties and because attorneys cannot dictate the content of other briefs in the case. Nevertheless, the benefits of including the right people and persuading the wrong people to stay home have long been recognized.[43] In this section, we summarize what we can learn from social science research about features of effective coordination.

1. A Full House

Judges and their clerks process briefs collectively; when they work on a case, they engage the arguments submitted as a compilation.[44] As a result, it makes sense to think about the impact of the briefs collectively. Empirical research shows that the side with more total briefs is more likely to win.[45] This pattern might reflect different mechanisms. A greater number of briefs often means that more information is provided in defense of a particular outcome.[46] This is especially true in light of the word limits courts place on briefs.[47] Findings that briefs with more words overall are more successful support this interpretation.[48]

However, the number of briefs impacts case outcomes even after controlling for the total number of words presented by each side.[49] This suggests that the number of briefs conveys an important signal to judges. Filing an amicus brief involves substantial investment typically; it is not a cheap enterprise.[50] Consequently, a large quantity of briefs on one side of a case signals a large number of relevant stakeholders who find the issue salient enough to invest resources.[51] There are also some indications that the justices notice if entities they would typically expect to be involved in an issue do not file a brief in a case.[52] They may be more skeptical about the strength of an argument in the absence of a reputable organization that would typically support that position. It is possible that when there are more briefs, that also means that the incidence of an expected briefer being absent is lower. In other words, when there are more briefs, it is less likely an expected participant has decided to stay home, thereby triggering judicial skepticism.

Increasing the number of briefs filed is not the only way to bring more people to the table. Filers can submit a single brief solo or as a coordinated group effort. Some scholars have found a connection between a larger number of cosigners to a brief and greater success.[53] This may operate as a signal of the number of affected groups in society.[54] Other social science research has examined the impact of the number of attorneys that draft a brief and finds that having more attorneys can also lead to a greater incidence of success.[55]

2. Experience in the Marble Palace

Gathering as many allies as possible is only one viable strategy. Not all participants play an equally important role in forging a strong collective set of arguments. It matters who is involved in the briefing as well as how many. Since attorneys craft the briefs, their experience level is critical to making persuasive arguments.[56] Repeated appearances before the Court provide an advocate with important insight into which approaches are more or less successful. The value of this insight is evidenced by the fact that the most experienced Supreme Court litigators can charge as much as $1,800 an hour.[57] The prior experiences of the entities that hire those attorneys can have an impact too.[58] The ACLU filed more briefs between 1984 and 2015 than any other interest group.[59] When they file a brief, it is based on a much deeper understanding of how to succeed in the Supreme Court compared to those who only rarely take interest in the work of the Court. Like any complex endeavor, practice makes perfect, or, in this case, practice enhances persuasion. Supreme Court practice is particularly specialized.[60] Both attorneys and filers with more experience in that arena are better equipped for success.

a. Attorneys Practicing Before the Court

Various empirical research demonstrates that attorneys who have appeared in a particular forum more frequently can achieve better client outcomes.[61] There are two primary theories for such an effect. The first explanation is that greater experience allows lawyers to understand the nuances of making more effective arguments.[62] For example, an attorney specializing in a particular practice area can develop detailed knowledge of the relevant law.[63] In Supreme Court litigation, frequent participation can lead to a greater understanding of the justices and how to frame arguments in ways that are unique to that forum.[64]

Even if an attorney new to the Supreme Court were to write a brief that was as well-crafted and persuasive as one written by a seasoned member of the Supreme Court bar, they might still be at a disadvantage in ultimately convincing the justices. As attorneys appear before a court repeatedly, they not only obtain important insight, but also gain the court’s trust.[65] That trust is a product of the long-term incentive structure of frequent litigators.[66] If an attorney appears before a court regularly, they know any departure from providing clear and faithful information will harm their reputation and, thus, decrease their long-term effectiveness.[67] An attorney who appears before a court only once may be tempted to shade the truth a bit or omit key elements since they do not have to worry about their future reputation.[68] There is evidence that Supreme Court justices fully understand these differing motivations and place their trust accordingly.[69] For example, one Supreme Court litigator who had formerly clerked on the Court noted that justices have “less trust and reliance” when dealing with attorneys they do not know.[70]

Just as not all briefs are created equal, neither are all experiences equal. All attorneys can gain knowledge and the trust of the Court through repeatedly appearing before it, but those who have clerked for a justice or served as the U.S. Solicitor General (S.G.) have the opportunity to develop both knowledge and trust on a whole other level.[71] Clerks have the opportunity to form a close working relationship with one justice and interact with others to some extent as well.[72] Firms pay former clerks large bonuses upon completing clerkships based largely on the assumption that they will have the fast track to influence their justice.[73] The empirical evidence on this point is mixed. For example, the side with more former clerks does gain more individual justice votes but is not more likely to win the case or shape the Court’s opinion.[74]

The job of the U.S. Solicitor General also provides an unparalleled level of access to the high court.[75] Since the S.G.'s job is to represent the United States in that forum, the S.G. accumulates extensive experience.[76] Unsurprisingly, such individuals are often high-profile Supreme Court litigators when they return to private practice.[77] However, we find that after controlling for the number of times former S.G.s appear in front of the Court, the fact that they have previously served as S.G. does not provide any additional benefit in terms of persuading the Court.[78] This suggests that experience gained through representing private clients can be just as beneficial as lessons learned by serving as S.G.

The current S.G. is another matter entirely.[79] Social science research routinely finds that the S.G. is much more successful in the Supreme Court than any other type of attorney.[80] The fact that this advantage does not continue after leaving the office suggests it is more attributable to the client, the federal government, than to the specific abilities of the S.G.[81] We now turn from attorneys to consider the role of their clients who are filing the briefs.

b. Filers Repeatedly Submitting Briefs

Another factor in coordinating the briefs is not just how many there are and who writes them but also who files them. The importance of the U.S. Solicitor General as a briefer highlights the fact that the entities filing briefs can matter too. Although empirical research pays relatively little attention to the experience of filers compared to attorneys, much of the same logic applies.[82] Those who routinely file Supreme Court briefs can gain key knowledge and reputational benefits.[83] Our research confirms that this is the case to some extent. Individual amicus briefs filed by more experienced filers are more similar to the majority opinion.[84] However, the briefs from a particular side of a case do not have a greater collective influence over the opinion when the filers have more experience.[85] Together, these findings indicate that filer experience is moderately important. While a single brief filed by those with extensive experience can shape the opinion, when all the briefs in a case are considered in the aggregate other factors appear to have an impact rather than filer experience.

3. Strange Bedfellows

There is a broader line of social science work that also has potential implications for effective coordination. Scholars have long theorized that signals are more persuasive if the source communicates a position usually understood to be against their interests.[86] That is, if a person says something that would generally go against their personal preferences, it is more believable because self-interest can be eliminated as a motivation for prevarication.[87] Consider an example in a legal context. If a leading law professor with known conservative leanings were to opine that the Supreme Court should resolve a pending case in a liberal manner, that opinion would be more persuasive to a neutral observer than if a liberal scholar made the same declaration.

Another aspect of this phenomenon pertains to usual foes uniting. For example, if well-known liberal and conservative law professors agree that the Court should resolve a case in a specific way, it is more persuasive. The fact that people from divergent viewpoints can reach a consensus increases the probability it is the correct result.[88] Although empirical research has yet to explore to what extent this operates in the context of briefing, theory suggests that a side has a greater chance of persuading the Supreme Court when the filers are more ideologically diverse.[89] Interest groups from opposite ends of the spectrum joining forces would presumably provide a strong signal for the Court. However, the utility of this approach may often be barred by the simple fact that such ideologically different groups usually want divergent outcomes[90] Next, we move on from discussing coordinating the strongest possible group of filers and attorneys to considering the briefs themselves and how attorneys write them.

B. Effective Writing Contributes to Successful Briefs

1. Good Writing

Law schools strive to prepare their students to be good writers.[91] There are journals dedicated to promoting skillful writing.[92] It is a key component in the practice of law.[93] Those attorneys in appellate practice focused on briefing are even more keenly interested in the quality of their writing.[94] This is certainly true regarding practice at the Supreme Court.[95]

What defines high-quality writing and how to measure it are not simple questions,[96] but quantitative research does help us dig into the specific aspects of writing that matter. Unsurprisingly, overall, the evidence is mixed.[97] But there is evidence of connections between elements of writing and both outcomes and opinions at the Supreme Court. For example, brief quality influences its reception by the Supreme Court, measured by a factor variable based on dictionaries[98] for passivity, lively language, and sentence complexity, along with a measure of sentiment.[99] Additionally, as proxied by attorney experience, higher-quality party briefs are associated with both winning outcomes and higher percentages of overlapping language in the majority opinion.[100]

a. How Plain Language Helps

As with many aspects of “good” writing, guides, jurists, and instructors highlight the importance of easy-to-understand language.[101] Social science research generally supports this focus. For example, there is evidence that justices are more likely to adopt language from amicus briefs that use higher percentages of language associated with cognitive clarity and plain language (as captured by shorter sentences).[102]

Scholars have also considered more nuanced assessments including evaluating the impact of the readability of a brief. A host of readability indexes seek to capture the extent to which readers will be likely to comprehend writings.[103] The most common automated indexes calculate the reading level (often expressed in terms of grade) using equations based on features of word, sentence, and passage lengths, as well as word frequency and syntactic consistency.[104] Attorneys have suggested such readability measures as valuable tools for practitioners.[105]

There are studies specifically focused on how the clarity or readability of briefs influences outcomes and opinion content.[106] Interestingly, briefs at the Supreme Court have become less accessible over time regarding readability.[107] There are mixed results on this front. One study failed to find evidence state, federal, or U.S. Supreme Court party brief readability influenced who won the case.[108] However, there is evidence that more readable briefs filed in support of motions for summary judgment in federal and state trial courts were more likely to be successful, though more so in federal courts.[109] We also found that readability did not have a significant effect on who won. Still, we did find that readability increased the similarity between the party and amicus briefs assembled on behalf of a side and the majority opinion.[110]

b. How Emotional Language Hurts

Social science research also generally bears out advice that briefers should avoid emotional language.[111] It may be of no surprise then that emotional language is relatively rare in merit briefs before the Supreme Court. However, it does still appear and has been fairly consistent over time.[112] Amicus briefs tend to contain more emotional language than party briefs.[113] Surprisingly, when controlling for other factors, both experienced filers and attorneys are more likely to use emotional language in party briefs, as are larger groups of filers and more experienced attorneys regarding amicus briefs. The number of attorneys on the brief, on the other hand, is associated with less emotional language in amicus briefs.

Social science research based on statistical analyses indicates that justices are less likely to vote in favor of a side where the party brief contains more emotional language.[114] Thus, generally, when attorneys draft briefs, they are well advised to avoid emotionality. However, this effect may not apply to all advocates equally. Additional research indicates that the effect of emotional language is gender specific, with male justices punishing male authors for its use while rewarding female briefers for its use.[115] This result indicates that men advocating for clients in front of male jurists should be particularly wary of making arguments using emotional terms, while women advocates may find it advantageous. Furthermore, we found that individual amicus briefs and collections of briefs for one side were more likely to influence the opinion content of a Supreme Court decision when they contained less emotional language.[116] This suggests that attorneys should avoid using such language in their briefs.

2. Quantity and Variety of Information

Beyond the quality of the writing, it is essential to consider the content of the brief, with specific attention to the amount and types of information it represents. Briefs vary in how much information they contain in simple and complex ways. Word limits (which vary by type of brief and change over time) can restrict the amount of information drafters can include. Even where word limits are constant, briefers may be more or less repetitive within briefs. For example, some drafters may reiterate the same arguments more than once in the same brief, while others do not. Additionally, the briefs vary in how much they bring new and unique information to the justices or repeat or echo other briefs and lower court opinions. Some briefs merely repeat information found in other documents before the Court, while on the other extreme some address wholly novel issues. The information within the briefs also varies in nature regarding the extent to which they address factual statements, legal arguments, citations, policy arguments, or other inclusions.[117] Furthermore, sometimes advocates make strategic decisions about how much or what type of information to include.

a. Quantity of Information

We see patterns regarding the production of information; generally, but not always, resources such as the number of attorneys signing a brief and attorney experience, both of which often reflect a filer’s wealth or clout, translate into more information being provided.[118] In terms of the overall breadth of information, measured by the number of words used within a brief, we found it increased in both amicus and party briefs based on the number of attorneys, attorney experience, and the number of former clerks.[119] Additionally, where there are more and more experienced filers, the amicus briefs contain more information overall. Both former and current S.G.s include less overall information in party briefs.

Beyond production, the quantity of words and citations shapes how judges and justices resolve cases and shape precedent. There is evidence that Supreme Court justices take more time to decide cases when the briefs contain more citations to precedent.[120] Additionally, the side with longer briefs and more briefs is more likely to win.[121] An amicus brief with more words and citations that are also in other briefs from the case impacts opinions more.[122] At the federal trial court level, the number of citations, along with their patterns and vitality, are associated with success on summary judgment motions.[123]

b. Variety of Information

While we have highlighted several areas where conventional wisdom regarding legal briefing is borne out in quantitative social science research, it isn’t always. One of the most important divergences is about repetitive information in amicus briefs. Legal writing guides, former Supreme Court clerks, justices, and other commentators all bemoan repetitive briefs assembled for a side.[124] The formal rules of the Supreme Court strongly discourage them.[125] Despite this, there is evidence that amicus briefs often repeat arguments from party briefs,[126] though other research finds they have little overlapping language with the lower court opinion, party briefs, and other amicus briefs.[127] Additionally, party and amicus briefs on a side can vary quite a bit in how similar they are to each other, but similarity is common.[128] Attorney experience also correlates with more similar briefs.[129]

Moreover, a consistent body of social science research using varying techniques has found that the side with more overlapping or similar information benefits. [130] Amicus briefs with new information are less likely to influence the majority opinion.[131] Similarly, amicus briefs with more overlapping language with the party brief they support and other amicus briefs on that side are more likely to influence the majority opinion.[132] Additionally, briefs with less novel language and precedents and fewer unique words and cites (amici only) impact opinions more.[133] Finally, the side with a smaller range of words used overall is more likely to shape the majority opinion.[134]

3. Strategic Drafting

A primary function of attorneys is to anticipate the outcome of litigation strategies and help clients obtain the best resolution possible.[135] In doing so, they must anticipate the likely arguments of the other litigants and how judges are likely to respond to different arguments.[136] Thus, it would be surprising if briefs did not reflect anticipatory behaviors. Such strategic calculations can include how to respond to and present information regarding lower court decisions, accounting for the likely tactics of opposing counsel, and appealing to majorities.[137]

a. Appeals to the Median

The idea that at least some litigants and amici intentionally target potentially pivotal justices is certainly not new.[138] At the Supreme Court, both justices and attorneys have discussed the importance of counting to five.[139] The idea has long been that amicus briefs target the so-called swing or median justices.[140] Practitioners have different approaches to crafting their briefs with specific justices in mind.[141] Our evidence indicates that both party and amicus briefs written by more attorneys and attorneys with more Supreme Court experience contain more strategic citations.[142] Filer experience and former clerks’ presence also increase the number of strategic citations in amicus briefs.[143] The opposite is true where more parties sign on to a party brief or a former S.G. is on an amicus brief.[144] We did find evidence that, as a whole, the side that collectively cites the current median justice[145] is more likely to win.[146]

b. Frames

Another strategic opportunity in briefing arises in the framing:[147] the crafting of briefs to accentuate specific issues in the case over others.[148] This type of behavior is common in approaching briefing.[149] Specifically, litigants change whether they use frames that reflect the norm in elite discourse (prevailing) or an alternative frame in Supreme Court litigation in response to how lower courts framed the issue in the opinions the justices are reviewing.[150] For example, in Bowers v. Hardwick, the attorneys and justices varied in terms of whether they framed the case in terms of a constitutional right to commit sodomy or a constitutional right to privacy.[151] The interplay between appellate and respondent framing also helps illuminate such a strategy. Evidence shows that such framing decisions matter but that the consequences of such decisions are shaped by both the frames selected by the lower court and opposing counsel.[152] For example, a respondent is less likely to obtain a favorable outcome if they don’t adapt their frame in the response brief when a petitioner has reframed their argument in the petitioner’s brief.[153]

4. Using Policy-Oriented Language

Based on the Supreme Court’s position at the apex of the judicial hierarchy and its place within the separation of powers system, policy arguments play a more central role in Supreme Court litigation than they tend to in other judicial settings.[154] Such policy-oriented considerations generally look like “legislative facts,” which take the form of information regarding the real-world consequences of the potential outcomes of cases.[155] Evidence shows that at least some justices are concerned about unintended consequences and actively seek such data to anticipate and avoid negative outcomes when crafting decisions.[156] Thus, providing such information in briefs may be beneficial. Our research specifically considers two types of policy-oriented information: technical and future-oriented.

a. Brandeis Briefs: Providing Technical Information

One of the most famous examples of the importance of technical information is the Brandeis Brief from Muller v. Oregon, which was one of the first briefs to rely on social science research to make claims regarding future policy implications of the case.[157] Justices and clerks both have noted that such information in briefs is particularly useful and desired.[158] The implications of a policy choice are not always clear, and those with technical expertise in the relevant social sciences can often shed important light on such matters. Additionally, many guides discuss the potential influence of such technical information.[159] Relying on measures of language about quantity and causation along with the use of parentheticals[160] to systematically estimate the presence of technical language, we found that party briefs that involved a greater number of filers and attorneys tended to include more technical language. In contrast, the opposite was true for such briefs filed by former S.G.s.[161] For amicus briefs, on the other hand, the number of attorneys on the brief and the participation of more experienced attorneys and former clerks were associated with greater shares of technical language. This indicates that experience leads attorneys to conclude that providing the Court with information regarding the potential impact of policy choices is an important element of persuasive briefing. On the other hand, briefs with more co-signers used less technical language.[162] This may reflect a tendency of filers with extensive knowledge of the relevant social science to file briefs on their own. In considering impact, we also found evidence that the side that collectively has a higher concentration of technical language is more likely to influence the majority opinion.[163] This is the best evidence that justices care about the downstream impact of their decisions; the side that spends the most time talking about that aspect of the case in their collective briefs has more impact over the opinion.

b. Discussing the Future Impact of Policy

Furthermore, we also considered the presence of future-oriented language in party and amicus briefs.[164] To do so, we measured the percentage of language in briefs that included future tense verbs.[165] First, we found that the presence of more experienced Supreme Court litigators and former clerks practicing before the Court used more future-oriented language in both party and amicus briefs and that experienced filers used such language more in amicus briefs.[166] We also found that the side with more future language is not more likely to win but does see an advantage in the similarity between the briefs for the side, both individually and collectively, and the majority opinion.[167]

III. Things Attorneys Can Strategize Around but Not Control

Next, we turn to characteristics of cases where attorneys have less control at the point at which briefing is relevant. These litigation features include lower-court-related features, such as if you are coming to the court having won or lost in the lower court, aspects of the lower court opinion, and the salience of the case while at the lower court; judge-related factors, such as characteristics of the lower court opinion, the ideology of the judge(s) deciding the matter, and aspects of oral argument; and more general conditions that often are captured by considering the term or year. While attorneys can control many facets, like whom they ask to brief and the content of their own briefs, these additional factors further shape whether briefing will be successful.

Of course, attorneys and parties have some control over the ramifications of these lower-court-related, judge-related, and general features. First, only losing parties from the lower courts can pursue appeals.[168] Attorneys will generally advise clients who lost in a lower court that pursuing review is advisable only where they are likely to win, such as when a majority of the judges or justices are inclined to rule in your client’s favor.[169] This does not mean that a disadvantaged party will never pursue review, as even a small chance of reversal and litigation costs may outweigh the costs of accepting a lower court decision.[170] For example, individuals facing the death penalty often have little incentive not to pursue review.[171] Additionally, potential respondents and appellees can try to sweeten settlements to avoid going before the appellate court and the possibility of creating unfavorable precedent.[172] But, conditional on being in front of the court, parties have little control over many of these issues.

A. Lower-Court-Related Factors

1. Procedural Position

First, the procedural position that your client is in, whether petitioner or appellee, can generally matter to the likelihood of success. Such determinations are specific to the level or type of court and tend to be complicated to assess due to selection bias issues.[173] At the Supreme Court, being a petitioner or appellant is generally better than being a respondent or appellee. Between 1946 and 2021, the Supreme Court reversed or otherwise nullified the lower court opinion in some form approximately two-thirds of the time.[174] Outright affirmances represent a little under thirty percent of the outcomes.[175] The advantage of petitioners and appellants is also apparent in quantitative studies, even when we control for other factors.[176] Scholars theorize this pattern arises from the fact that reversals are more impactful on the overall state of the law and the Supreme Court in the modern era has nearly unlimited docket control: in other words, justices get more doctrinal and legal bang for their buck in terms of changing the state of the law by taking cases that are likely to reverse.[177] So, procedural position indicates the likelihood of success.[178] Apart from the types of litigation strategies described in Section III.A, procedural position is not malleable.

2. Lower Court Opinions

The length of the lower court opinion likely acts as a proxy for the complexity of the underlying case that is likely to influence the outcome of the case.[179] Additionally, the length of the lower court opinion indicates how much material there is in that opinion from which a higher court judge can borrow. Our prior research on the Supreme Court demonstrates that longer lower court opinions result in a lower likelihood that individual justices vote in favor of the petitioner and less similarity between Supreme Court opinions and both party and amicus briefs.[180] Such findings suggest that the Supreme Court is more likely to produce opinions that diverge from the briefs in complex cases.

3. Lower Court Amicus Participation

Amicus participation is common at the Supreme Court but far rarer in lower courts.[181] Thus, cases with amicus participation in the lower court are unusual. The presence of such briefing below likely indicates the case is particularly salient.[182] Previous work has shown that amicus activity in the lower court indicates that petitioners are less likely to win at the Supreme Court and that the opinion will be less similar to party and amicus briefs.[183] These prior findings indicate that briefs are less influential in prominent cases.

B. Judge-Related Factors

1. Ideology

Within social science research on judicial decisionmaking, particularly political science, there is a wealth of research indicating that the ideology of judges matters in the decisions they make.[184] This is particularly true at the Supreme Court, where we tend to see the largest effects.[185] It is less true as we go down the judicial hierarchy.[186] While scholars debate the nature of judicial ideology and how best to measure it,[187] there is strong evidence that justices have prior dispositions that make some outcomes more likely than others.[188] Additionally, there is evidence that ideology does not influence whether the Court will cite a brief but does influence whether the majority opinion will include language borrowed from an amicus brief.[189]

2. Oral Arguments

There is also research indicating that oral arguments matter regarding votes and outcomes.[190] Prior work indicates that the more questions asked of a side at oral argument, the less likely that side is to win.[191] This may result from existing hostility to a side or its arguments.[192] Or it could result from additional scrutiny; Justice Roberts implied the latter when he asserted, “[T]he secret for successful advocacy is simply to get the Court to ask your opponent more questions.”[193] There is also evidence that the quality of the argument matters.[194] However, attorneys draft briefs before these elements are known. Thus, advocates are unable to leverage information about the number of questions asked in oral arguments in their specific case when crafting a brief. They can, however, seek to increase the number of questions asked of the other party with the information they include.

C. General Litigation Environment

Finally, factors such as the conditions present within a specific time period, such as the term or year, can matter.[195] Variables for term and year likely pick up unspecified aspects of the environment in the court and society at large. For example, both the availability of technology that helps with legal research and writing and the sophistication of the Supreme Court bar have increased over time.[196] Litigants and their attorneys are extremely unlikely to be able to exert much control over such factors other than the extent to which they can make decisions as to pursuing review and strategizing regarding settlement.[197] Attorneys should consider these factors in assessing the likelihood of success and the extent to which appeals and briefing are worth the costs to their clients.

IV. How Much Can These Factors Matter?

One of the benefits of empirical social science is that it provides a way to test what matters and estimate how much things matter. Furthermore, we can provide such estimates in a way that answers questions lawyers care about. In this section, we leverage the power of regression analysis to provide insight into both the collective impact of the individual factors we have discussed and whether advocates can take any of those factors too far.[198] First, we explore how much controllable factors can shape two vitally important aspects of Supreme Court litigation: who wins and the content of the majority opinion. Second, we examine whether maximizing individual elements can ultimately become detrimental. In other words, when can there be too much of a good thing? These analyses constitute novel contributions to understanding how data can inform appellate practice.

A. What Happens if You Maximize all the Things You Can Control?

Being able to control things that may help lead to positive outcomes is an important starting point, but it raises the question of how much these factors matter. And how much do they matter overall? We take on this question by estimating the maximum advantage generated by manipulating all controllable factors (hereinafter “controllables”) to the greatest extent possible.[199] In essence, we are calculating the ceiling on how much the characteristics we study can affect who wins and what the Court discusses in the opinion. After all, if extensive efforts can garner only minimal gains, there may be little reason to make such investments.

To account for the factors outside the participants’ control, we estimate the maximum advantage gained from controllables in two situations. In the best-case scenario, all the uncontrollable factors are ideal; in the worst-case scenario, they are as bad as possible. Considering these two scenarios allows us to consider whether efforts to maximize the advantage on the things that an attorney can control have more potential upside when you have an uphill battle or when the wind is at your back. In this way, we explore both what effect filers and attorneys can have and when their efforts and investment can provide the greatest returns.

1. Maximum Advantage over Case Outcome

First, we estimate the maximum advantage an advocate can gain regarding the probability of their side winning the case. We calculate this advantage by comparing all the briefs, filers, and attorneys for one side to those on the other.[200] The factors that lawyers can control include the number and variety of words and Supreme Court citations, the number of briefs, the number of citations to the sitting median justice, technical language, future-oriented words, clarity, emotionality, the number and experience of filers and attorneys, and the number of former clerks and former Solicitors General.[201] The maximum advantage is how much a side can increase the probability of winning when every such variable moves from its worst to best value in the dataset.[202] The uncontrollable factors we account for include the participation of the current Solicitor General, how many briefs were invited by the Court, the justices’ ideology, the length of the lower court opinion, the presence of amici in the lower court proceeding, and the term.

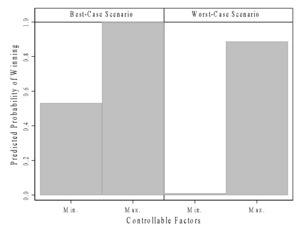

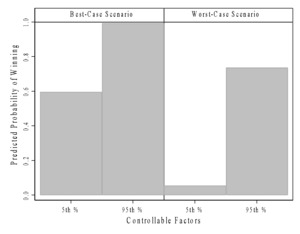

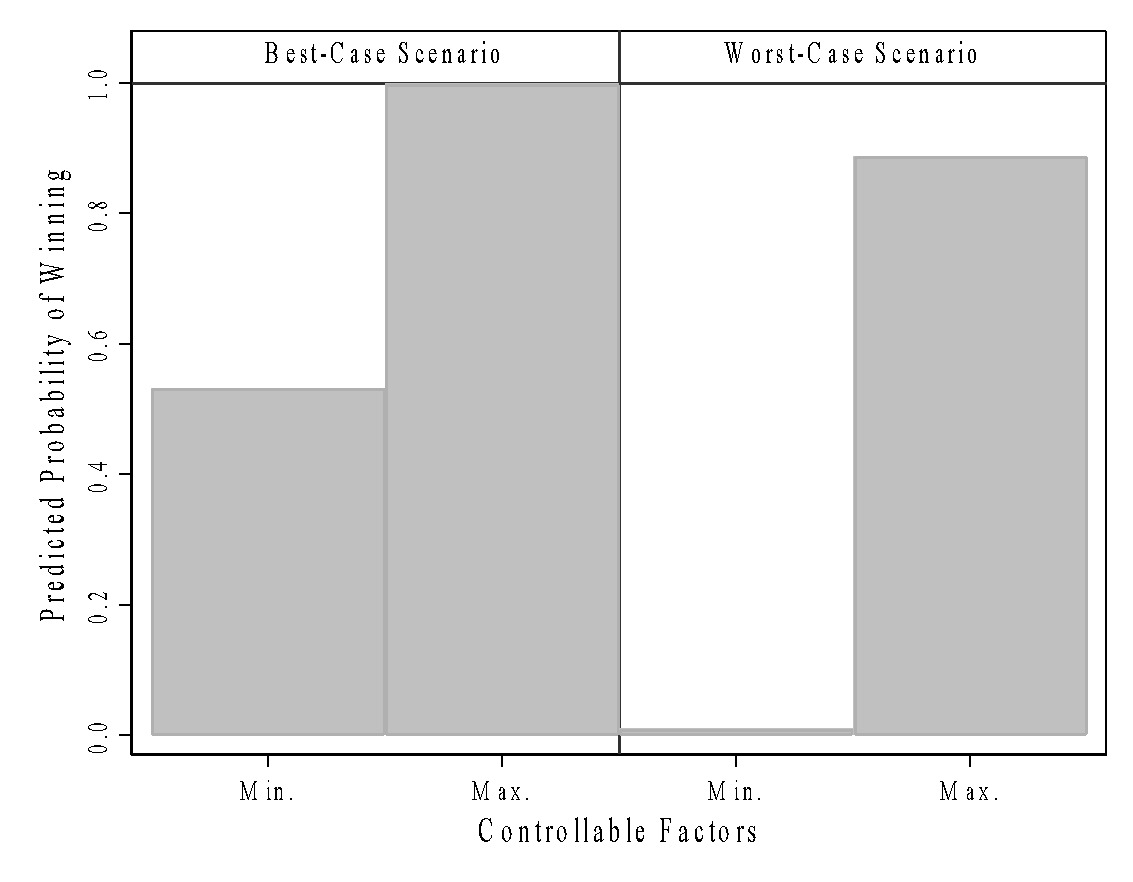

Figure 1 shows our findings. In the best-case scenario, the maximum advantage is an increase of 0.47 (p=0.74) in the probability of winning.[203] When all the factors an advocate can manipulate are at their worst possible values, a side wins an estimated 53% of the time. On the other hand, that number jumps to 99.9% when those variables are as beneficial for a side as possible. In the worst-case scenario, in terms of all the things beyond an attorney’s control, the maximum advantage is even greater at 0.88 (p=0.20). Here, the minimum values on controllable factors nearly guarantee a loss, with only a 1% chance of winning. However, maxing out all the controllables gives a side an 89% chance of winning. While these are only estimates of what happens in the most extreme situation, they illustrate that aspects within the participants’ control can substantially impact the chance of victory.

Using maximum and minimum values has the dual advantages of being intuitive and revealing the absolute ceiling in terms of possible advantage. However, such values in a large dataset can be quite unusual relative to the rest of the data. Therefore, we also consider the advantage that an attorney can gain when setting all the variables to their 5th and 95th percentile values instead of minimum and maximum. These are more realistic low and high values. We call these estimates the modified maximum advantage. They are depicted in Figure 2. Under the best-case scenario, the modified maximum advantage is 0.40 (p=0.21), and under the worst-case scenario, it is 0.68 (p=0.07). These still represent very substantial jumps in the probability of winning a case. The prize available appears to be well worth the effort. Attorneys should encourage their clients to build the largest and most experienced group possible in terms of both those who file the brief and the attorneys who write it. In the course of drafting, attorneys can benefit from seeking to provide longer and more well-cited discussion that is narrowly focused, unemotional, drafted clearly, and contains substantial discussion of the future impact of policy.[204]

2. Maximum Advantage over Majority Opinion Language

Litigants care about more than just who wins and loses each case before the Supreme Court.[205] The content of the majority opinion largely shapes the legal fortunes of future actors.[206] A major objective of briefing is often as much to shape this language as it is to sway votes.[207] As such, there is reason to care about how briefs shape opinions. Other fields have long used formulas and algorithms that reliably calculate two texts’ similarities.[208] In the same way that typing a query into a search engine will lead to related websites, we can estimate how similar the briefs are to the majority opinion. The metric we use, cosine similarity, ranges from zero to one.[209] Two documents with all the same words have a similarity measure of one, and two documents with no overlapping words whatsoever have a score of zero.[210] To look at the collective impact of briefs on an opinion, we combine all briefs on each side of a case and treat them as a unit. Then we calculate the similarity of all those briefs to the majority opinion. For each case, we have two estimates, one for the similarity of the petitioner-side briefs to the opinion and the other for the respondent-side briefs.[211]

Figure 3 shows that when it comes to influencing the opinion text, the maximum advantage is the same in best-case and worst-case scenarios: 0.99 (p < 0.001).[212] The entire range of the variable is one, so this advantage represents virtually the whole of possible variation. In other words, the controllable factors related to brief content and the number and experience of participants can entirely influence opinion content on their own regardless of the uncontrollable circumstances pertaining to the composition of the Court and other procedural factors.

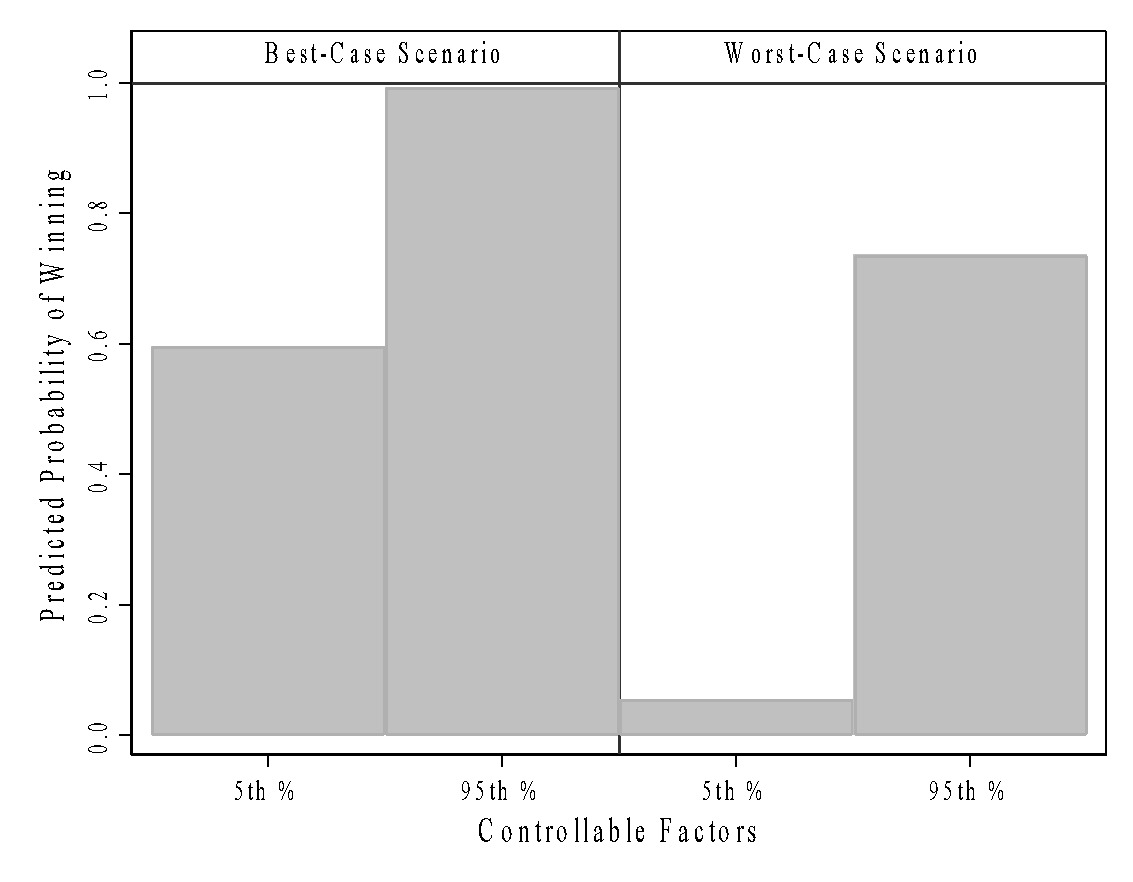

The modified maximum advantage shown in Figure 4 illustrates that even this more conservative estimate of the possible benefit is still quite large. It is also still very similar in the best and worst-case situations. When the controllable factors are at their 5th percentile value, the similarity to the majority opinion is 0.2 in the best-case and 0.18 in the worst-case scenario. These numbers both rise to 0.96 when the controllables are at their 95th percentile values. In other words, the modified maximum advantage all the briefs on a side can collectively have on opinion content is 0.76 (p < 0.001) if the uncontrollable factors are in their favor and 0.78 (p < 0.001) if they are not. The picture that emerges is startling: when it comes to the collective impact all the briefs for one side in a case can have, there appears to be almost no ceiling on how much they can shape opinion language.

While the lack of limitation on coordinated information provision is interesting to note, as a practical matter, it is usually only one brief that is amenable to substantial control. Therefore, as a follow-up, we measure the maximum advantage (and modified maximum advantage) when controlling the features of only a single brief. Since the parties themselves can have less control over some aspects, such as their own previous experience, we estimate the effect for amicus briefs.[213] Figure 5 shows that the maximum advantage an attorney can gain by moving controllable factors from their minimum to maximum in a single amicus brief is 0.97 (p < 0.001) in the best-case and 0.96 in the worst-case scenarios. In Figure 6, the modified maximum advantage is a more modest 0.68 (p < 0.001) in both situations. In short, whether looking at the impact of all briefs or a single brief on opinion language, the uncontrollable factors play a minimal role, and the possible advantage to be gained is considerable. The features of a brief and those who commission and compose it can shape the language of the law.

B. Can You Go Too Far?

While our empirical analysis indicates several ways that advocates can seek to enhance their impact on the Court, a word of caution is in order. Patterns in the existing data that show a link between more of a particular factor and greater success do not necessarily mean that more will always be better. It may be possible to go too far. For example, excessive citations to the median justice may generate derision rather than persuasion if the targeted justice concludes such efforts are blatant appeals to their ego. While the question of how much is too much may often be a matter of insight gleaned by those who frequently interact with the Court, empirical analysis can also provide information concerning this question.

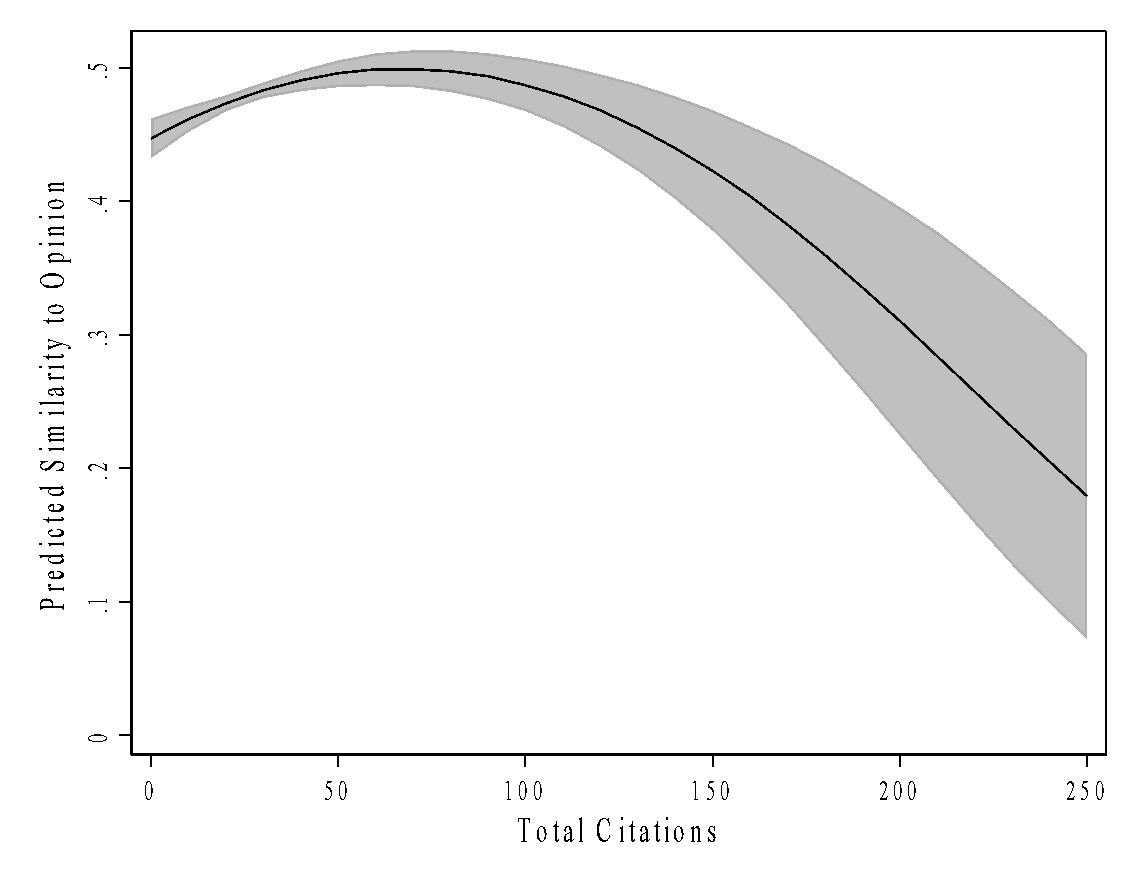

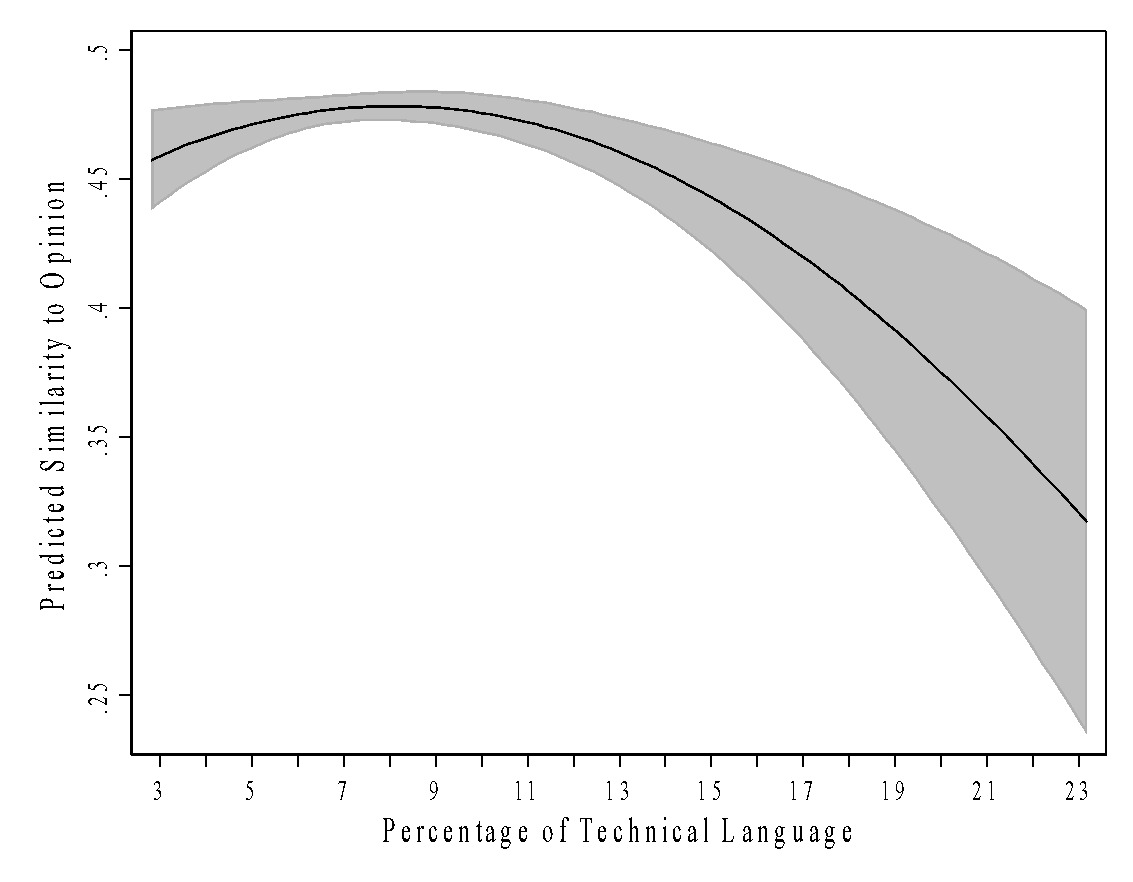

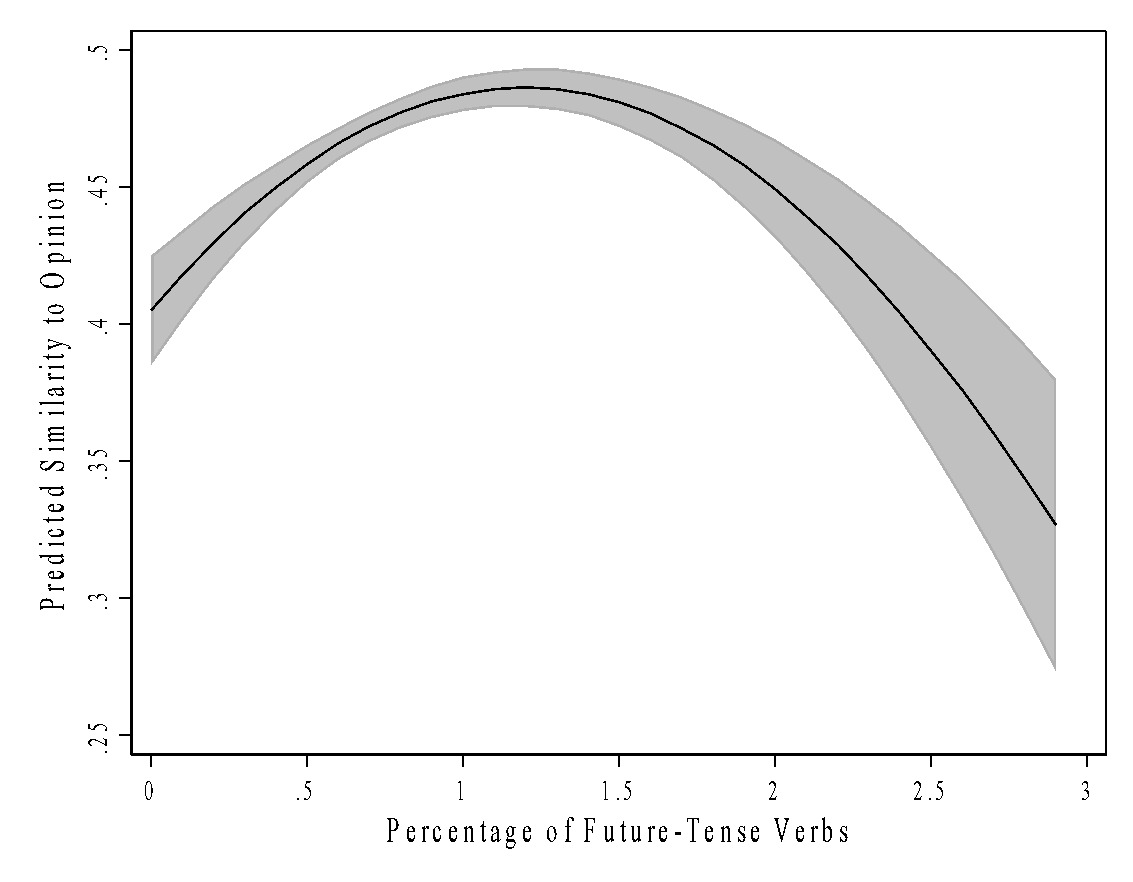

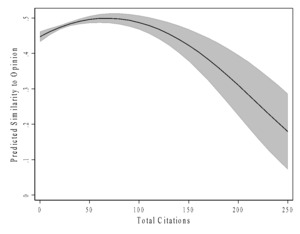

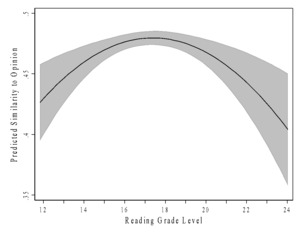

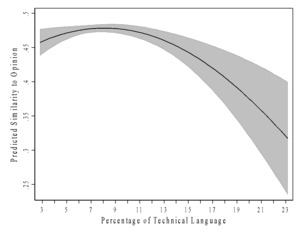

To shed light on the possible limits of our findings, we return to our estimates of how much an amicus brief can influence the language in the majority opinion. However, we use a different modeling strategy to observe if and when a factor’s effect diminishes or reverses direction.[214] Not surprisingly, this analysis indicates that there are limits to the benefit of some factors.[215] The word limit the Court imposes on briefs[216] places natural limits on the information in a brief, but putting too much of some good things within the allowable pages can still be possible. For example, Figure 7 shows that while more citations to Supreme Court cases are generally beneficial, the cap on the benefit appears to be approximately ninety citations. After that point, increasing the number of cites diminishes the overall similarity to the opinion language. Figure 8 indicates that while the clarity of a brief is often beneficial, it is possible to use language that is too simple and basic. Briefs written below the reading level of a college graduate impact the opinion less as they get increasingly simple, just as those that are more complex than that also have a negative impact. This suggests the sweet spot is to draft briefs at a reading grade level of about sixteen to eighteen. Figures 9 and 10 illustrate that using too much technical language and referring to the future too frequently can also be possible. Focusing too much on future policy implications and social science can result in a brief having less impact on the majority opinion.

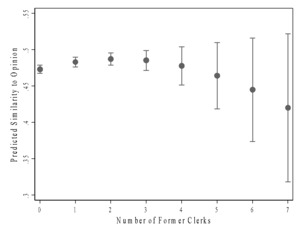

Unlike the contents of briefs, neither the number of cosigners and attorneys on a brief nor either of their experience level shows evidence of similar limitations. For example, Figure 11 shows the ever-increasing impact of how often the most experienced filer has previously submitted a brief to the Court.[217] There are likely to be diminishing returns for adding numbers or experience of participants at some point, but the advantages might simply slow down rather than reverse course. The one exception regarding participants is that the benefit of employing former Supreme Court clerks extends to only two or three clerks. Figure 12 suggests that adding more is associated with lower similarity to the opinion after that point. This may simply be a product of loading up on the big guns in particularly challenging cases. These findings (and other social science research) can supplement a legal advocate’s toolbox regarding the challenging task of appellate advocacy by suggesting ways to fine-tune written argumentation to maximize its efficacy.

Conclusion

Crafting an effective brief is an art. But that art can be informed by science. Understandably, those who dedicate their career to developing the legal expertise necessary to master the art of effective briefing have little time to devote to conducting scientific analysis as well. Fortunately, several social scientists (including ourselves) have dedicated as much painstaking effort and dedication to investigating the measurable qualities of effective briefing as practitioners have invested in honing their craft. The findings we report and the analyses we conduct in this Article are based on thousands of briefs containing hundreds of thousands of citations and millions of words. Social scientists have used their years of training in computational text analytics and statistics to distill that vast store of data into useful insights for advocates in the trenches of appellate litigation.

Empirical research documents a range of brief features associated with a higher likelihood of winning the desired outcome, shaping the language of the majority opinion, or both. Importantly, many of these features are within the control of those participating in an appeal, either as parties or amici and their attorneys. First, appellate briefs do not stand alone. They are part of the larger group of briefs submitted to a court arguing for a particular outcome. As a group, briefs are more effective when there are more briefs, and those who file them have greater experience. Such experience can come from multiple sources. For example, amici who regularly file briefs with a court, attorneys who frequently write such briefs, and attorneys who previously clerked or served as Solicitor General produce more effective briefs. Consequently, it is beneficial for interested parties to coordinate to present a collection of briefs with many experienced filers and attorneys.

Second, there are many manipulable features of individual briefs that can enhance their effectiveness. Lawyers are taught the importance of good writing from the first semester of law school. Just as many legal writing experts advise, we also find that clear, concise, and unemotional prose is most effective. In the context of briefing, providing technical details and discussing future implications are also beneficial to judges who must shape legal policy on a wide range of topics, usually without personal expert knowledge. Since appellate courts are multi-member bodies, another effective brief-writing tactic is to appeal to the potential median voter. Getting the all-important tie-breaking vote can be the difference between winning and losing. One strategy for currying favor with a particular justice in this way is to cite their authored opinions. Finally, the overall quantity and variety of information in a brief matter. More information is better, but a greater variety is not. Rather, an effective briefing strategy is to focus more carefully on fewer topics or arguments instead of casting the net broadly.

Finally, we provide important insight into two key follow-up questions about how these empirical findings can benefit appellate advocates. Just because factors influence key outcomes like who wins or how a court writes its opinion does not mean advocates should invest time and energy into shaping them. It is important to know how much these factors matter. Our models indicate that the potential upside is considerable. Even after accounting for the aspects of litigation that you cannot control, such as court- and judge-related factors, the benefits are well worth the effort. Second, we examine the question of whether an attorney can go too far. How much of a good thing is too much? We find evidence that this should be a concern concerning five factors in particular: total citations, clarity of text, technical discussion, future-oriented language, and the number of attorneys with clerkship experience. When these variables are at more extreme levels, they have a negative rather than a positive impact.

Despite the emergence of generative A.I., its tendency to hallucinate non-existent citations highlights that even the most advanced technology has limitations. It is likely that experienced and talented legal advocates will always best perform the nuanced task of brief writing. However, such individuals can benefit from the insights provided by social scientists who have leveraged large amounts of data with the help of cutting-edge technology.

Appendix

In the following sample brief, all emotional language is noted in bold, technical language is underlined, and future-oriented language is italicized.

Amicus brief filed by the American Psychological Association Task Force on the Rights of Children and Youth[218]

Gertrude M. Bacon, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Ingraham v. Wright

430 U.S. 651 (1977)

STATEMENT

We respectfully submit this brief based on the following resolution passed by the Council of Representatives—the governing body of the American Psychological Association.

The right of protection afforded to every human being against physical encroachment on their bodies without their consent is one of the most important protections afforded by the Constitution.

The wisdom of the Supreme Court to cautiously consider any decision permitting violence is well evidenced by its overruling mandatory enforcement of capital punishment—and specifically permitting this Writ of Certiorari—opposing corporal punishment in schools.

It is clear that the Constitutional issue of “cruel and unusual punishment” must be periodically reconsidered as it applies to any form of officially sanctioned physical violence.

It is especially relevant since the public school is the only institution which permits corporal punishment. For example, the armed forces, the prisons, and state hospitals, et al., specifically forbid corporal punishment.

Is Corporal Punishment Unusual?

Historically, many western cultures have used spanking, caning, paddling, whipping, and flogging as methods of “beating the devil” out of errant children. Most societies do not currently believe that devils inhabit the bodies of young children.

However this particular form of punishment continues although the original meaning has lost validity.

In fact, in the civilized world many countries have long since abandoned corporal punishment in schools. Among them are Poland, Luxembourg, Holland, Austria, France, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, Cyprus, Japan, Ecuador, Iceland, Italy, Jordan, Qatar, Mauritius, Norway, Israel, The Philippines, Portugal, and all Communist block [sic] countries.

New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Maryland have state laws prohibiting corporal punishment in the schools, as have many cities including the District of Columbia, Chicago, Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia.

It is therefore evident from a numerical point of view that corporal punishment is increasingly considered “unusual” as a practice to facilitate learning and improve behavior.

If a method of learning is effective it should be continued as a usual practice.

If it is not effective it should be discontinued and therefore is unusual.

Misbehavior in an educational setting, generally refers to behavior which impedes learning. However, educational and psychological research indicate that the use of corporal punishment and any punitiveness has a deleterious effect on learning.

The practice of corporal punishment provides a sanction for the use of violence as a solution to learning and behavior problems. Violence teaches counter-violence which encourages open hostility by children against schools.

A recent study conducted in Portland, Oregon, has shown that as corporal punishment increases in a particular school there is an increase in student vandalism against the school (Maurer, 1976).

Where corporal punishment has been sustained and encouraged as an aid to the learning process, it has been found ineffective. In fact, there is substantial evidence from the research in positive reinforcement, that children learn much more effectively in the absence of corporal punishment.

Therefore it is clear that if a method is shown to work it should become the “usual” method. It would be “unusual” for educators, faced with scientific data and the opinion of experts, to endorse a practice which is ineffective as being the “usual” method of pedagogy.

The United States Supreme Court, in Baker v. Owen, stated that “corporal punishment of children is today discouraged by the weight of professional opinion” (Holtzman, 1976).

The National Education Association Report on the Task Force on Corporal Punishment (1972) took a strong stand against the practice and offered many viable alternatives for motivating children to learn.

Despite the weight of professional opinion, some behavioral scientists maintain that there is not sufficient evidence to demonstrate the specific negative effects of corporal punishment. There never will be the type of controlled research that some require for scientific proof. Our laws, ethics, and morals forbid the practice of using human “guinea pigs.”

From animal research we know that avoidance behavior is the first response to pain. If escape is impossible, the organism will attack anything available—an otherwise peaceable cagemate, a tennis ball, the cage or even itself (Azrin & Holtz). Translated into human terms we find the child will first try to escape, by lying, by accusing others, by wriggling or by truancy, daydreaming or school phobia. If escape is impossible, he becomes aggressive and fights with his “cagemates.” Biting and scratching at the cage is certainly vandalism and this too we find resulting from excessive punishment.

Lastly, when no other recourse is left the animal bites himself. We also see in some extreme cases child suicidal behavior, usually described as “self destructive.”

Why Is Corporal Punishment Cruel?

It is cruel because it is inflicted most often upon children who are struggling with a variety of developmental and social problems which are related to their self image. The American Psychological Association has indicted in an official statement that “punishment intended to influence ‘undesirable’ responses often creates in the child the impression that he or she is an ‘undesirable’ person; and an impression that lowers self-esteem and may have chronic consequences.”

It is “cruel” because it hurts. This is a fact recognized by all criminal statutes in evaluating assaults as crimes, differing only in degrees.

Most important there is never assurance that the teacher or administrator conducting the punishment can always control his or her own feelings to properly separate them from the “degree” of pain involved as solely related to the “offense.” As in the case of Ingraham v. Wright over-zealous “punishers” can cause such physical damage that children may become severely injured and require hospitalization.

Does the United States Supreme Court feel that it can truly draw the line necessary for the welfare of children whom it has always protected?

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the American Psychological Association’s Task Force on the Rights of Children and Youth implores the United States Supreme Court to follow its wisdom of reversing its own decisions when their results have been proven ineffective.

Specifically, we request its reconsideration in reversing its former decisions permitting corporal punishment in schools.

We feel that this practice is ineffective as well as cruel and unusual and is disadvantageous to all the parties concerned.

See Allen v. Milligan, No. 21-1086, Vide 21-1087 (U.S. June 8, 2023), https://www.supremecourt.gov//docket/docketfiles/htm;/public/21-1086.html [https://perma.cc/VAD7-ZHU5]; see, e.g., Sup. Ct. Inst., Georgetown Univ. L. Ctr., A Look Ahead, Supreme Court of the United States, October Term 2022, 10 (noting that “[a] betting person would not bet against the Court finding some way to complete the trifecta in this case”), https://www.law.georgetown.edu/supreme-court-institute/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2022/09/OT22-Term-Preview-Final.pdf [https://perma.cc/HLW4-XZN2]; Madeleine Carlisle, Prepare for Another Blockbuster Supreme Court Term, Time (Sept. 26, 2022), https://time.com/6216673/supreme-court-cases-preview/ [https://perma.cc/E4K5-ACPM]; Jeff Neal, Supreme Court Preview: Merrill v. Milligan, Harvard L. Today (Sept. 23, 2022), https://hls.harvard.edu/today/supreme-court-preview-merrill-v-milligan/ [https://perma.cc/TS5T-L6N8]; Catherine Rowland & Graham Steinberg, What the Supreme Court’s Next Term Could Mean for the Future of Voting Rights and American Democracy, The Explainer: Cong. Progressive Caucus Ctr. (Sept. 15, 2022), https://www.progressivecaucuscenter.org/supreme-court-democracy [https://perma.cc/QH23-2M8W].

See Allen, supra note 1 (U.S. Feb. 7, 2002).

Morgan L.W. Hazelton & Rachael K. Hinkle, Monkey Cage, What Influences the Supreme Court? Here’s What We Learned, Wash. Post (Oct. 3, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/10/03/supreme-court-term-rulings-amici/ [https://perma.cc/HD75-3PE5].

Id.

Id.

Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S. 1 (2023).

Ian Millhiser, Surprise! The Supreme Court Just Handed Down a Significant Victory for Voting Rights, Vox (June 8, 2023), https://vox.com/scotus/2023/6/8/23753932/supreme-court-john-roberts-milligan-allen-voting-rights-act-alabama-racial-gerrymandering [https://perma.cc/36DN-QC5C]; Ed Pilkington, Turning Point or the Long Game: What’s Behind John Roberts’s Surprise Supreme Court Voting Rights Ruling?, Guardian (June 10, 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/us-new/2023/jun/10/john-roberts/us/supremecourt-voting-rights-decision [https://perma.cc/VT9Y-SMXA].

Kate Murphy, The Supreme Court’s Most Surprising Decisions this Term, from Voting Rights to Native American Adoptions, Yahoo! News (June 30, 2023), https://news.yahoo.com/the-supreme-courts-most-surprising-decisions-this-term-from-voting-rights-to-native-american-adoptions-193453313.html [https://perma.cc/F6TC-WRJH]; Ari Berman, Today’s Giant Supreme Court Surprise Ruling Is a Rare Win for Democracy, Mother Jones (June 8, 2023), https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2023/06/supreme-court-allen-v-milligan-voting-rights-act-alabama/ [https://perma.cc/B3UN-3C97].

Kimberly Strawbridge Robinson & Lydia Wheeler, Roberts, Kavanaugh Shock With Liberal Voting Rights Victory, U.S. L. Week (June 8, 2023), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/roberts-kavanaugh-shock-with-liberal-vistory-on-voting-rights [https://perma.cc/33NV-3C5L].

Cristian Farias, John Roberts’s Shocking Defense of Black Voting Rights, Vanity Fair (June 8, 2023), https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2023/06/john-roberts-supreme-court-voting-rights-ruling [https://perma.cc/JX66-2KT4]; see also Robert Barnes & Ann E. Marimow, Why Supreme Court Voting Rights Decision Shocked Legal, Political Worlds, Wash. Post (June 12, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/06/12/voting-rights-supreme-court-history-alabama-roberts [https://perma.cc/CS4A-PGGM].

Richard L. Hasen, Opinion, John Roberts Throws a Curveball, N.Y. Times (June 8, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/08/opinion/milligan-roberts-court-voting-rights-act.html [https://perma.cc/SL5G-VMZ7].

Mark Sherman, Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Black Alabama Voters in Unexpected Defense of Voting Rights Act, A.P. News (June 8, 2023), https://apnews.com/article/supreme-court-redistricting-race-voting-rights-alabam-af0d789ec7498625d34430a4327367fe [https://perma.cc/77CA-D3QY].

See generally, e.g., Paul M. Collins, Jr., Friends of the Supreme Court: Interest Groups and Judicial Decision Making (2008); Morgan L.W. Hazelton & Rachael K. Hinkle, Persuading the Supreme Court: The Significance of Briefs in Judicial Decision-Making (2022); Ryan C. Black, Matthew Hall, Ryan J. Owens & Eve Ringsmuth, The Role of Emotional Language in Briefs Before the U.S. Supreme Court, 4 J.L. & Cts. 377 (2016); Pamela C. Corley, The Supreme Court and Opinion Content: The Influence of Parties’ Briefs, 61 Pol. Rsch. Q. 468 (2008); Adam Feldman, Counting on Quality: The Effects of Merits Brief Quality on Supreme Court Decisions, 94 Denv. L. Rev. 43 (2016); Susan B. Haire & Laura P. Moyer, Advocacy Through Briefs in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 32 S. Ill. U. L.J. 593 (2008); Adam M. Samaha, Michael Heise & Gregory C. Sisk, Inputs and Outputs on Appeal: An Empirical Study of Briefs, Big Law, and Case Complexity, 17 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 519 (2020).

See generally, e.g., Lee Epstein & Andrew D. Martin, An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research (2014).

See generally Hazelton & Hinkle, supra note 13 (addressing a wide range of studies regarding briefs from across disciplines); Paul M. Collins, Jr., The Use of Amicus Briefs, 14 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 219 (2018) (discussing a wide range of studies from across disciplines regarding amicus briefs).

E.g., Black, Hall, Owens & Ringsmuth, supra note 13 (party briefs); Collins, supra note 13, at 3 (amicus briefs); Kayla S. Canelo, The Supreme Court, Ideology, and the Decision to Cite or Borrow from Amicus Curiae Briefs, 50 Am. Pol. Rsch. 255 (2021) (amicus briefs); Corley, supra note 13 (party briefs); Feldman, supra note 13 (party briefs); Haire & Moyer, supra note 13 (party briefs); Thomas G. Hansford & Kristen Johnson, The Supply of Amicus Curiae Briefs in the Market for Information at the U.S. Supreme Court, 35 Just. Sys. J. 362 (2014) (amicus briefs); Samaha, Heise & Sisk, supra note 13 (party briefs). But see generally Lee Epstein & Joseph F. Kobylka, Supreme Court and Legal Change: Abortion and the Death Penalty (1992); Hazelton & Hinkle, supra note 13.

See generally Collins, supra note 15.

For example, amici file briefs in fewer than 2% of cases in the federal circuit courts. Rachael K. Hinkle, Publication and Strategy in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 179 J. Institutional & Theoretical Econ. 121, 141 (2023); cf. Paul M. Collins, Jr. & Wendy L. Martinek, Friends of the Circuits: Interest Group Influence on Decision Making in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 91 Soc. Sci. Q. 397, 398-99 (2010) (“[W]hile it is true that, in percentage terms, there is more amicus curiae participation in the U.S. Supreme Court than in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, in raw numbers much more amicus curiae participation occurs in the latter compared to the former.”); Sarah F. Corbally, Donald C. Bross & Victor E. Flango, Filing of Amicus Curiae Briefs in State Courts of Last Resort: 1960-2000, 25 Just. Sys. J. 39 (2004); Lee Epstein, Exploring the Participation of Organized Interests in State Court Litigation, 47 Pol. Rsch. Q. 335 (1994); John Harrington, Amici Curiae in the Federal Courts of Appeals: How Friendly Are They?, 55 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 667, 675-77 (2005); Wendy L. Martinek, Amici Curiae in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 34 Am. Pol. Rsch. 803, 806-09 (2006).

Stephen M. Shapiro, Kenneth S. Geller, Timothy S. Bishop, Edward A. Hartnett & Dan Himmelfarb, Supreme Court Practice: For Practice in the Supreme Court of the United States § 13.11(f) (11th ed. 2019).

Samaha, Heise & Sisk, supra note 13; Haire & Moyer, supra note 13; see also sources cited supra note 18.

See generally Collins, supra note 15.

See generally Paul M. Collins, Jr., Friends of the Court: Examining the Influence of Amicus Curiae Participation in U.S. Supreme Court Litigation, 38 L. & Soc’y Rev. 807 (2004) [hereinafter Collins (2004)]; Paul M. Collins, Jr., Lobbyists Before the U.S. Supreme Court: Investigating the Influence of Amicus Curiae Briefs, 60 Pol. Rsch. Q. 55 (2007) [hereinafter Collins (2007)]; Gregory L. Hassler & Karen O’Connor, Woodsy Witchdoctors Versus Judicial Guerrillas: The Role and Impact of Competing Interest Groups in Environmental Litigation, 13 B.C. Env’t Affs. L. Rev. 487 (1986); Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill, The Influence of Amicus Curiae Briefs on the Supreme Court, 148 Univ. Pa. L. Rev. 743 (2000); Minjeong Kim & Lenae Vinson, Friends of the First Amendment? Amicus Curiae Briefs in Free Speech/Press Cases during the Warren and Burger Courts, 1 J. Media L. & Ethics 83 (2009); Kevin T. McGuire, Repeat Players in the Supreme Court: The Role of Experienced Lawyers in Litigation Success, 57 J. Pol. 187 (1995); Thomas R. Morris, States Before the U.S. Supreme Court: State Attorneys General as Amicus Curiae, 70 Judicature 298 (1987); Sean Nicholson-Crotty, State Merit Amicus Participation and Federalism Outcomes in the U.S. Supreme Court, 37 Publius: J. Federalism 599 (2007); Karen O’Connor & Lee Epstein, The Importance of Interest Group Involvement in Employment Discrimination Litigation, 25 Howard L. J. 709 (1982); Steven Puro, The Role of the Amicus Curiae in the United States Supreme Court: 1920–1966 (1971) (Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York at Buffalo); Robert Rushin & Karen O’Connor, Judicial Lobbying: Interest Groups, The Supreme Court and Issues of Freedom of Expression and Speech, 15 Se. Pol. Rev. 47 (1987). But see generally Morgan L.W. Hazelton, Rachael K. Hinkle & James F. Spriggs, The Long and the Short of It: The Influence of Briefs on Outcomes in the Roberts Court, 54 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol’y 123 (2017) [hereinafter Hazelton et al. (2017)]; Morgan L.W. Hazelton, Rachael K. Hinkle & James F. Spriggs II, The Influence of Unique Information in Briefs on Supreme Court Opinion Content, 40 Just. Sys. J. 126 (2019) [hereinafter Hazelton et al. (2019)].

Hazelton & Hinkle, supra note 13, at 56–57; Feldman, supra note 13, at 66–67; see also, e.g., Roy B. Flemming & Glen S. Krutz, Repeat Litigators and Agenda Setting on the Supreme Court of Canada, 35 Can. J. Pol. Sci. 811 (2002); Stacia L. Haynie & Kaitlyn L. Sill, Experienced Advocates and Litigation Outcomes: Repeat Players in the South African Supreme Court of Appeal, 60 Pol. Rsch. Q. 443 (2007); Reginald S. Sheehan & Kirk A. Randazzo, Explaining Litigant Success in the High Court of Australia, 47 Austl’n J. Pol. Sci. 239 (2012); John J. Szmer, Susan W. Johnson & Tammy A. Sarver, Does the Lawyer Matter? Influencing Outcomes on the Supreme Court of Canada, 41 Law & Soc’y Rev. 279 (2007).

See generally, e.g., Adam J. Berinsky, Rumors and Health Care Reform: Experiments in Political Misinformation, 47 Brit. J. Pol. Sci. 241 (2015); Randall L. Calvert, The Value of Biased Information: A Rational Choice Model of Political Advice, 47 J. Pol. 530 (1985); Rune Slothuus & Claes H. de Vreese, Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning, and Issue Framing Effects, 72 J. Pol. 630 (2010); cf. Morgan L.W. Hazelton, Rachael K. Hinkle & Michael J. Nelson, The Elevator Effect: Contact and Collegiality in the American Judiciary 143 (2023).

Hazelton & Hinkle, supra note 13, at 56–59; Justin Wedeking, Supreme Court Litigants and Strategic Framing, 54 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 617, 618 (2010). See generally Feldman, supra note 13.

E.g., Epstein & Kobylka, supra note 16, at 5–8. See generally Hazelton & Hinkle, supra note 13; Collins, supra note 15.

See, e.g., sources cited supra notes 13, 16.

E.g., Epstein & Martin, supra note 14, at 194.