Introduction

This article examines some of the pedagogical implications of current empirical research, including studies involving Self-Determination Theory (SDT)[1] and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT),[2] for legal writing instruction. One of the three fundamental psychological needs that decades of SDT research has identified is autonomy, understood as the perception of one’s own actions and decisions as volitional and self-directed.[3] Moreover, empirical studies specifically aimed at law students and legal professionals have identified autonomy and autonomy support as the most important factors correlated with wellness and wellbeing, as well as life and work satisfaction.[4] These findings are consistent with a growing body of literature within legal pedagogy aimed at encouraging law students to become more autonomous, resilient, creative, and self-directed learners and problem solvers.[5] And legal writing courses—particularly required first-year courses—present a unique opportunity for cultivation of autonomy within the law school curriculum.

But there are important countervailing considerations. Current cognitive learning research suggests a need to temper, or at least guide, this enthusiasm for autonomy, especially in the context of first-year courses in law school. The growing body of CLT research has expanded and clarified our understanding of the cognitive limitations and parameters that impinge upon students’ capacity to act autonomously.[6] CLT research underscores the cognitive limitations that impact students’ wellbeing as they grapple with learning a set of complex skills, such as those involved in a first-year legal writing course.[7] Additionally, research has increasingly identified the cognitive aspects of wellness and wellbeing, including emotional regulation and responding to stress.[8]

What is needed, therefore, is a balanced approach to autonomy cultivation for first-year courses that takes into account the cognitive limitations novice learners experience, all within a context of seeking to promote wellness and wellbeing for students as human beings. Accordingly, this article proposes the organizing concept of “guided autonomy” to articulate a middle way between potential extremes. The recommended approach relies heavily on guidance materials and exercises designed to cultivate and empower students’ autonomy and decision-making with sufficient structure to enhance acquisition of problem-solving skills. Examples of such materials are included as appendices.

Part I reviews the pertinent research on wellbeing and cognition (including SDT and CLT), with a focus on application to educational instruction. This section explores the tension between cultivating student autonomy and reducing cognitive load in legal writing education. It proposes a balanced approach that prioritizes autonomy while minimizing unnecessary cognitive burden. Although some cognitive load can benefit learning, excessive load may hinder decision-making and thwart acquisition of problem-solving skills. By providing decision aids to guide students’ problem-solving strategies, professors can help students develop autonomy while managing cognitive demands.

Part II examines the opportunity presented in first-year legal writing courses for guided autonomy and provides specific, concrete recommendations for faculty members teaching first-year legal writing courses. This section proposes a “guided autonomy” approach for teaching legal writing that balances student independence with necessary support; it also highlights legal writing courses as ideal for cultivating autonomy due to their focus on independent work and problem solving. Emphasizing the need to address three key steps in legal problem solving (problem design, solution generation, and solution presentation), the section recommends strategies such as providing decision aids, templates, and worked examples to help students manage cognitive load while developing decision-making skills. It also suggests implementing real-time exercises and personalized feedback to enhance learning and support autonomy in legal writing education. Specific examples of guidance materials are included in the appendices.

Part III considers potential challenges to the guided autonomy approach. This section identifies three main sources of resistance: institutional aversion to prioritizing student wellbeing over traditional academic goals; student resistance due to unfamiliarity and the demanding nature of autonomous learning; and professors’ internal doubts about adopting a less controlling teaching style.

The article concludes with a review of limitations on our current understanding and a call for further inquiry and empirical examination of optimal techniques and methods, identifying opportunities for further exploration and experimentation.

I. What We Know: Summary of Current Pertinent Research on Wellbeing and Cognition

This section summarizes key implications of Self-Determination Theory and Cognitive Load Theory research for cultivating autonomy among law students against the backdrop of the wellbeing crisis in law schools and the legal profession. Part I.A summarizes the findings of wellbeing research among law students and lawyers and highlights the potential for autonomy cultivation to improve law students’ wellbeing. Part I.B examines the self-determination theory research, with an emphasis on the role of motivation within academic instruction and the importance of autonomy support in student engagement and learning. Part I.C examines the cognitive load research, with an emphasis on instructional approaches for enhancing skill acquisition in the context of legal problem solving. Part I.D proposes a balanced approach to cultivating autonomy among law students by prioritizing autonomy while managing cognitive load through decision aids and guided instruction.

A. The Wellbeing Crisis in Law Schools and the Legal Profession

Law schools and the legal profession are facing a well-documented wellbeing and wellness crisis, with alarmingly consistent rates of depression, suicide, substance abuse, and other maladies at a level much higher than that of other professional groups.[9] At the same time, these problems correlate with negative effects on professionalism, performance, job satisfaction, and competence.[10]

One of the key findings from the groundbreaking and influential Sheldon and Krieger studies of law students and lawyers is the strong correlation between autonomy and wellbeing, including job satisfaction and life satisfaction.[11] These findings are consistent with research over the past three decades in a wide variety of fields and contexts, which similarly have found a strong correlation between autonomy and wellbeing.[12] In workplace studies, autonomy has proved to be particularly important, in combination with demand levels, as a significant factor correlated with increased wellbeing and decreased stress.[13] Moreover, the relatively high level of demand in many legal jobs further enhances the relative importance of autonomy in avoiding or mitigating the negative effects of stress.[14] Thus, the research findings to date suggest that cultivating autonomy among students while in law school could help to address the ongoing wellbeing crisis within the profession.[15] Research has also found that autonomy cultivation may increase academic performance among law students, including both higher grades and improved bar-passage results.[16] Further, there is some indication that autonomy-oriented instruction may particularly benefit minority, underrepresented, and underserved students, as well as students with ADHD, autism-spectrum conditions, and other varieties of neurodiversity.[17] Moreover, the general aim of increasing autonomy is at least broadly consistent with several other developing movements within legal pedagogy.[18]

Not surprisingly, then, some scholars, professors, and practitioners have taken up the call to cultivate autonomy among law students, including in legal writing courses.[19] The published results on these efforts to date have been somewhat limited, however, with a particular dearth of empirical research to identify specific pedagogical techniques and methods that actually help improve the wellbeing and academic performance of law students. One aim of this article is to contribute to these efforts but to do so in a way that incorporates countervailing considerations stemming from the cognitive limitations experienced by students as novice learners.

B. Self-Determination Theory Research

The literature on autonomy discussed above is based primarily on self-determination theory (SDT).[20] SDT is “a macro theory of human motivation” that has been developed over the past fifty years and applied in a wide variety of contexts, from education to business, medicine, sports, and even parenting.[21] SDT has generated a rich body of research and has been tested and implemented across cultures, in numerous countries and regions around the world.[22]

The centerpiece of SDT is the identification of three factors for human flourishing: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. SDT research posits these three factors, in the form of basic psychological needs, as essential requirements for all human beings. Put simply:

[P]eople need to feel that they are good at what they do or at least can become good at it (competence); that they are doing what they choose and want to be doing, that is, what they enjoy or at least believe in (autonomy); and that they are relating meaningfully to others in the process, that is, connecting with the selves of other people (relatedness).[23]

SDT research has shown that these three factors intertwine and interrelate. Thus, autonomy cannot develop separately and independently of the other two factors, and autonomy should not be pursued at the expense of the other concomitant basic psychological needs.[24] One of the primary foci of SDT research has been motivation: how to encourage beneficial actions in a way that is most conducive to both wellbeing and performance, in light of these three basic psychological needs.[25]

1. Autonomy in SDT Research

Given the centrality of autonomy within SDT, one must understand its precise meaning in the SDT construct, as it differs from many ordinary uses of the term. Within SDT, “autonomy” is a psychological need to perceive one’s own actions and decisions as volitional and self-directed.[26] The distinctive feature of experiences of autonomy within SDT is thus volition, or perceiving one’s actions as originating within the self.[27] Accordingly, autonomy entails “a sense of initiative and ownership in one’s actions.”[28] Note the critical role that perception plays with respect to autonomy. Autonomy within the SDT understanding is a matter of perception, rather than some independent, objective status or circumstance.[29]

Although “autonomous” in common parlance is often used synonymously with “independent,” autonomy within the SDT construct does not mean independence.[30] Indeed, an individual can perceive a dependent or required action as autonomous to the extent that they experience the decision whether to perform the given action originating from within the self.[31] Thus, for example, an individual can experience autonomy with respect to the action of complying with a command where the individual believes that doing so is beneficial or worthwhile—so long as the individual perceives the action of compliance as being volitional, rather than forced.[32]

2. Motivation in SDT Research

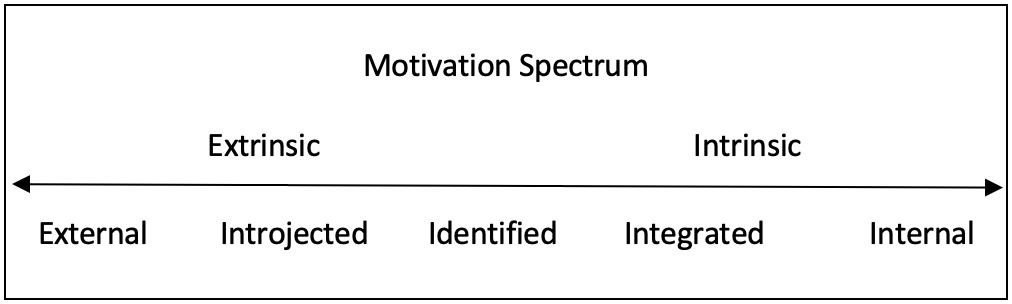

Motivation is a critical concept in the SDT literature. The pioneers of SDT research, Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, articulated a theory of motivation that posits that individuals’ motivation to engage in a behavior is not simply a matter of either being motivated or not; rather, there are different types of motivated behavior, each with different qualities.[33] SDT recognizes two broad categories of motivation—extrinsic and intrinsic—and posits that an individual’s motivation occurs along a continuum from external to internal, or from controlled to self-determined.[34] This basic continuum is depicted below in Figure 1.[35]

When an individual is extrinsically motivated to perform an action, the motivation comes from outside the individual, typically in the form of either a reward or a punishment.[36] By contrast, when an individual is intrinsically motivated, they perform the action for its own sake or for the inherent enjoyment or satisfaction of the activity itself.[37] Intrinsically motivated actions “are experienced as wholly volitional, as representative of and emanating from one’s sense of self, and they are the activities people pursue out of interest when they are free from the press of demands, constraints, and instrumentalities.”[38] Such actions also typically involve “curiosity, exploration, spontaneity, and interest in one’s surroundings.”[39]

Generally, SDT research in a wide variety of contexts has demonstrated that extrinsic (controlling) motivation is associated with negative outcomes (both with respect to wellbeing and performance), whereas intrinsic (autonomous) motivation is accompanied by positive outcomes.[40]

The nature of an individual’s motivation greatly influences their engagement, their acquisition and retention of knowledge, and their ability to apply knowledge to new situations.[41] Moreover, SDT research has demonstrated that the nature and quality of an individual’s motivation to engage in activities depends strongly upon the individual’s social and environmental contexts.[42] Contexts that promote more intrinsic forms of motivation are those that “facilitate satisfaction of the three basic needs—by providing optimal challenge, informational feedback, interpersonal involvement, and autonomy support.”[43] Accordingly, educators have an opportunity to set up autonomously-supportive contexts for their students through instructional design.[44]

One of the most important insights from SDT research for educators is that the use of techniques and methods that appeal to the extrinsic end of the spectrum has an undermining effect on individuals’ motivation, performance, and wellbeing.[45] So, for example, “offering people extrinsic rewards such as money or awards for performing an intrinsically interesting task tended to decrease their intrinsic motivation for that activity.”[46] One primary driver of this dynamic appears to be the individual’s perception that the extrinsic reward has thwarted their own self-determination; thus, the extrinsic reward shifts “people’s perceived locus of causality from internal to external, leaving them feeling like pawns to the extrinsic controls.”[47]

Nevertheless, students—like most human beings—have an innate, natural desire to socialize that brings with it the capacity to progress from the extrinsic end of the motivational spectrum to the intrinsic end.[48] As social beings, we “naturally internalize the regulation of socially sanctioned activities to feel related to others and effective in the social world,” and thus we “integrate those regulatory processes to maximize [our] experience of self-determination.”[49] Indeed, this capacity for individuals to progress along the continuum from extrinsic (least autonomous) to intrinsic (most autonomous) motivations presents one of the chief opportunities for teachers in working with students.

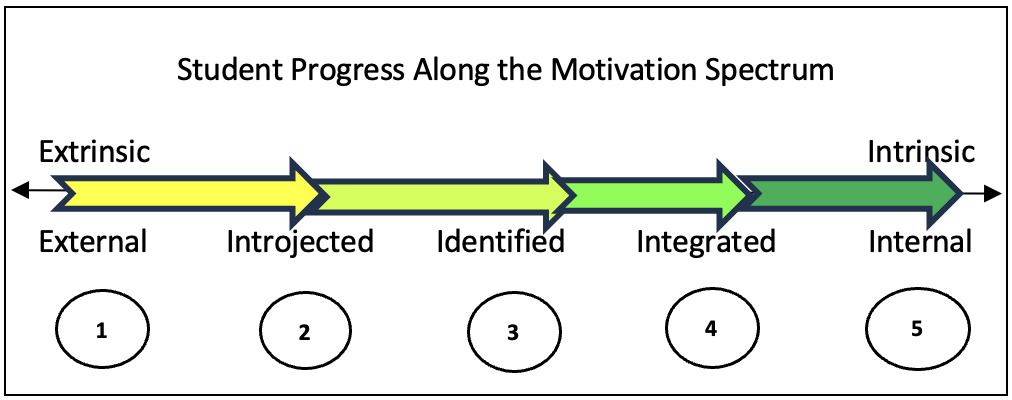

In an educational context, beginning students rarely engage with assignments and other activities in a course out of pure intrinsic motivation, sheerly for the inherent enjoyment of the activity; typically, students begin closer to the extrinsic end of the spectrum.[50] The goal, then, is to create incentives and conditions that conduce to students’ migration from extrinsic motivation toward intrinsic motivation, as depicted in Figure 2. Students thus can progress through increasing identification with, and integration of, the educational aims of activities within the course. Of course, one should not expect that a student will proceed neatly and inexorably through these five stages; for most students, progress is not linear, and their motivation at any given point in time can be either further to the left or further to the right on this continuum with respect to any particular task.[51] Nevertheless, faculty can and should seek long-term progress for students over time, even if that process is only begun during school and continued after graduation as they continue to develop their skills through further practice.[52] Importantly, an educator’s use of techniques and methods that rely on extrinsic motivators (such as awards, rewards, scores, or threats of punishment) will tend to impede the student’s progression along this continuum toward intrinsic motivation.[53]

A student in the first type of motivation, external regulation, is motivated solely by the promise of an external reward or the threat of an external punishment.[54] Although at this stage the student’s actions are intentional (they are being successfully motivated to act), the student will perceive that this action is controlled, rather than self-determined, because the action is dependent on external contingencies.[55] As an example, a student in the external regulation stage might choose to attend law school because of overt pressure from his parents coupled with the threat of being cut off from financial assistance if he fails to do so.

A student in the second type, introjected regulation, has internalized some of the expectations placed on them by others and thus is motivated by the desire to avoid negative feelings such as guilt and shame and to experience positive feelings such as pride.[56] Such a student is motivated by the belief that they should perform the action or complete the task at hand and would feel guilty or ashamed if they did not do so.[57] Although a student in the introjected regulation form of motivation is less dependent on external rewards or threats, they still perceive their actions as coerced or controlled by factors imposed on them from outside the self.[58] Thus, for example, a student in the introjected regulation stage might prepare a legal memorandum because it was a required assignment and she did not want to disappoint the professor.

A student in the identified regulation type has personally identified with the course activities and thus perceives them as useful, beneficial, or important to accomplish their own personal goals.[59] In this instance, the student engages in the activity at hand because they see the personal value or importance of doing so.[60] Such a student’s “personal importance results from one’s having identified with the underlying value of the activity and thus having begun to incorporate it into one’s sense of self.”[61] An example of a student exhibiting this type of motivation would be a legal writing student who works hard on a legal research exercise because it involves a skill that he believes employers will expect him to be able to demonstrate.

A student in the integrated regulation stage has integrated the activities in the course into their core values and personal identity.[62] Although a student in this stage is still extrinsically motivated, the student identifies with and aligns with the activity at hand to such an extent that they view it as consistent with their own developing sense of a coherent self.[63] A student in this stage, for example, may complete multiple rounds of revisions to an appellate brief draft and seek out additional feedback because being an effective advocate is part of her developing professional identity.

The final form of motivation is where the student engages in the activity for pleasure intrinsic to the activity itself, action for its own sake.[64] This intrinsic motivation can take any of three forms: (1) “intrinsic motivation to know”; (2) “intrinsic motivation to accomplish”; and (3) “intrinsic motivation to experience stimulation.”[65] With intrinsic motivation to know, the student engages in the activity “for the pleasure of gaining knowledge and exploring new ideas.”[66] The intrinsic motivation to accomplish entails the positive feelings that one experiences when “mastering a challenging task.”[67] And the intrinsic motivation to experience stimulation involves engaging in activities for the pure “enjoyment, fun, or excitement inherent in them.”[68] Thus, a student who has reached this stage may seek out extra practice sessions for an oral argument or participate in a moot court competition simply because she loves the thrill of engaging in debate, thinking on her feet, and articulating compelling arguments.

Numerous studies have demonstrated, in a wide variety of contexts, that certain techniques and methods are generally perceived as controlling and thus tend to undermine individuals’ progression toward intrinsic motivation or preservation of pre-existing intrinsic motivation. Examples of these techniques and methods are offering money, threatening punishment, imposing deadlines, grading, and providing critiques.[69] Grading on a strict curve, in particular—as is commonly done for 1L legal writing courses in law school—substantially undermines students’ autonomy and their progression toward intrinsic motivation.[70] The negative tendency of these can be offset to some extent, however, by the messages communicated alongside them, as well as the style in which they are implemented.[71] For example, avoiding controlling language (such as “you must,” “you have to,” or “you should”), acknowledging the student’s feelings, and emphasizing available choices can reduce the inherent tendency for more controlling elements of a course to undermine the student’s progression along the continuum toward intrinsic motivation.[72]

By contrast, an educator’s style of communication and interactions with students can exacerbate the negative tendency of externally-oriented motivators through the use of controlling approaches such as promising prizes, imposing pressure, making threats, or performing displays of authority.[73] Persistent use of external motivators can lead, inter alia, not only to aggression and resistance but also to passivity and “learned helplessness,” in which the student “comes to believe that his or her behavior has no direct effect on the outcome of the situation.”[74] Thus, the decisions an educator makes with respect to communications, course design, and style of interaction with students can significantly affect students’ progression along the motivational continuum.[75]

3. Role of Autonomy Support in Educational Applications of SDT Research

Building from the central motivational construct discussed above, SDT researchers in educational contexts and educators seeking to apply SDT research have developed the concept of “autonomy support” to describe contexts, approaches, styles, and actions teachers can implement to encourage students’ progression along the motivational continuum.[76] At the heart of autonomy support is the recognition that students benefit—both with respect to wellbeing and learning—in contexts that help to cultivate their autonomy.

In large measure, to date, applications of SDT to education have focused on what teachers can do. SDT researchers have identified three primary communication and interaction techniques teachers can implement to maximize integration and minimize undermining of intrinsic motivation: (1) providing meaningful rationales or explanations; (2) acknowledging feelings; and (3) emphasizing choice rather than control.[77] It should be no surprise, then, that educators seeking to apply SDT findings to improve outcomes for their students have tended to advocate for these three core techniques.[78]

Commentators have also attempted to sketch out, in general terms, certain attributes of teachers and styles of teaching that are typically associated with autonomy support. For example, autonomy-supportive learning environments and teaching approaches are those that generally “maximize student involvement and self-direction and minimize teacher-controlled actions.”[79] And “autonomy-supportive teachers distinguished themselves by listening more, spending less time holding instructional materials such as notes or books, giving students time for independent work, and giving fewer answers to the problems students face.”[80] Moreover, such teachers tend to “avoid[] giving directives, consistently prais[e] mastery, avoid[] criticism, giv[e] answers less often, and respond[] to student-generated questions and statements with empathy and perspective taking.”[81] Instead, they are “responsive,” “flexible,” and “motivate through interest.”[82] In sum, an autonomy-supportive classroom provides a “learning communit[y] in which students have meaningful roles in setting classroom rules, feel safe to explore and take risks, are supported to solve problems and set personal goals, and are responsible for monitoring and evaluating their progress.”[83] General guidance includes suggestions to provide options from which the students can choose; base instruction on students’ interests and preferences; and promote independent actions and decision-making.[84]

There has been much less examination of the students’ side of this equation, however; particularly, the mechanisms and limitations involved with the experience of learning. Perhaps this is due, in part, to SDT’s emphasis on the natural and innate quality of the big three factors.[85] Within the SDT perspective, students—like all human beings—have a natural capacity and desire to grow, to learn, to face and overcome challenges, and to adapt to their social environments.[86] Accordingly, then, within certain corners of the SDT school of thought, learning may be viewed as a more or less natural process that will take place under the right circumstances, like a flower blossoming when the optimal conditions of soil, water, and sunlight are provided.[87]

But there is an important issue lurking here: In addition to students’ natural capacities to learn, there are also certain—equally natural—limitations on those capacities that educators can and should take into account.

There is already a hint in this direction in the critical role played by students’ perceptions within the SDT framework. Although early research tended to focus on autonomy as simply a de facto circumstance—i.e., assuming that certain individuals are simply fortunate enough to be given autonomy in their work, while the more unfortunate are not—recent studies have emphasized that the degree to which an individual may benefit from the opportunities for exercising autonomy depends on their mindset and perception.[88]

Moreover, experienced educators, especially those who teach writing and other skills-based courses, have long recognized the need to take into account students’ status as novice learners; a recognition that suggests some need to temper the emphasis on autonomy for these students.[89] As discussed in more detail below, recent research on the cognitive aspects of learning—especially when novice learners confront complex tasks—provides a critical counterpoint to SDT, suggesting that teachers take a moderated approach to autonomy that includes guidance that is tailored to such students’ particular needs. This shift in focus from teaching to learning presents an important opportunity to calibrate the goal of autonomy cultivation to the difficulties faced by first-year law students in legal writing courses.

C. Cognition Research

The cognitive aspects of autonomy cultivation in legal writing courses become particularly important when considering the effects of cognitive load on students, especially when learning skills necessary to complete complex tasks such as conducting legal research and preparing legal memoranda, briefs, and other forms of legal analyses and argumentation.[90] The cognitive aspects of emotional experiences and stress also amplify the importance of pedagogical approaches informed by considering the cognitive load parameters of legal writing coursework.[91] These cognitive aspects can be influenced by curricular design, institutional culture, instructional methods, and situational contexts in an educational setting, such as in a law school legal writing program.[92]

1. Cognitive Limitations for Novice Learners

Consideration of cognitive limitations, especially among novice students, counsels in favor of a balanced approach that recognizes that efforts to encourage autonomous learning and decision-making must be tempered by use of more explicit guiding instructions.[93] A leading body of empirical research and theoretical examination of pertinent cognitive limitations at work in the learning process can be found among Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) researchers.

CLT seeks to “optimize learning of complex cognitive tasks by transforming contemporary scientific knowledge on the manner in which cognitive structures and processes are organized (i.e., cognitive architecture) into guidelines for instructional design.”[94] One of the theoretical foundations for CLT is the distinction between (1) knowledge that is biologically, or evolutionarily, primary; and (2) knowledge that is biologically, or evolutionarily, secondary.[95] Biologically primary knowledge does not require explicit instruction, and is generally “unconscious, effortless, rapid, and driven by intrinsic motivation.”[96] Biologically secondary knowledge, in contrast, does generally require explicit instruction, as it is cultural knowledge that humans have not evolved to acquire.[97] Such knowledge is “conscious, effortful, and often needs to be driven by extrinsic motivation.”[98]

Critically, for the present discussion, writing in all forms—including legal writing—involves biologically secondary knowledge.[99] Therefore, acquisition of legal writing skills must take place within the confines of human’s cognitive architecture.[100]

One of the key features of this architecture, as described in CLT, is the necessity of working with two separate memory stores when processing new information or acquiring non-evolutionarily primary skills: (1) a very limited working memory; and (2) a nearly unlimited long-term memory.[101] Working memory is “severely limited in both capacity and duration.”[102] With respect to capacity, an individual typically can only keep approximately 5-9 separate items of information in working memory at any given point in time.[103] And that individual can only hold these items active in working memory for approximately 20 seconds.[104] A classic example of these limitations is the difficulty most people have in memorizing sequences of numbers higher than 7 or 8 digits.[105] When the learner’s working-memory capacity is exceeded, the knowledge sought to be conveyed cannot be encoded into long-term memory.[106]

As a result, there is a bottleneck whenever a learner confronts new information, especially in situations involving complex skill acquisition, due to the limited capacity of working memory.[107] Indeed, “the limits of [working memory] are especially relevant in common situations in which people are learning complex tasks that heavily deplete [working-memory] resources.”[108] Accordingly, nearly all newly acquired information in such contexts must pass first through the narrow window of working memory before it can be stored in long-term memory.[109] On top of this, utilization of working memory during most problem-solving activities involves not only storage of information but also active processing, and these two activities operate simultaneously in a manner that easily can drain the limited available working-memory resources.[110]

Unlike the narrow confines of working memory, long-term memory affords a much more capacious storage and retention facility. Information that successfully passes through working memory into long-term memory typically can be retained, more or less intact, indefinitely.[111] The degree of difficulty with which new information can pass through working memory and be integrated into long-term memory depends heavily on the existing structures within the memory stores of that particular learner and the relationships or connections available for the learner to make use of based on those structures. The term “schema” describes a structured constellation (or “chunking”) of elements within long-term memory that is available to the learner for integration of new knowledge:

Cognitive schemas are used to store, organize, and reorganize knowledge by incorporating or chunking multiple elements of information into a single element with a specific function. Their incorporation in a schema means that only one element must be processed when a schema is brought from LTM to WM to govern activity.[112]

According to the “borrowing-and-reorganization principle” of CLT, “most of the new information stored” in long-term memory “is obtained by imitating what other people do, listening to what they say, and reading what they write. This new knowledge is reorganized by combining it with existing knowledge.”[113] Through repeated instances of similar task performance—i.e., extensive practice—learners over time “may incorporate a huge amount of information and eventually be triggered without depleting [working-memory] resources.”[114] This process, referred to as “schema automation,” is what enables experts to perform complicated tasks and routines.[115] Whereas a novice confronting the same task would engage with it as a giant number of independent and interacting elements, the expert, through reliance on her existing system of conceptual schemas, engages only with a limited number of such elements, through “the building of increasing numbers of ever more complex schemas by combining elements consisting of lower-level schemas into higher-level schemas.”[116]

When a novice learner confronts a new complex task, she lacks the extensive structure of preexisting conceptual schemas to enable effective use of working-memory resources.[117] Therefore, the opportunity confronting the educator is to aid the student in allocating working-memory resources and constructing effective conceptual schemas, through instructional design and teaching methods.

2. Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load

When acquiring skills that are biologically secondary, a learner will have to allocate the available working-memory capacity to the task at hand. The term “cognitive load” denotes the capacity taken up through this allocation.[118] The concept of cognitive load can also be broken down into two components: (1) mental load; and (2) mental effort.[119] Mental load refers to the amount of resources demanded by the instructional parameters, whereas mental effort is “the amount of capacity that is allocated to the instructional demands.”[120] Standing at the crossroads of these two components, the student must decide whether (and how) to allocate the resources necessary to meet the demand.[121] As a result, attempts by the professor to set demand levels appropriately through instructional design “will only be effective if subjects are motivated and actually invest mental effort in them.”[122]

CLT researchers in the educational context have identified three categories of cognitive load based on the relationship between such load and the educational task at hand: (1) intrinsic; (2) extraneous; and (3) germane.

Intrinsic cognitive load is that which is necessary to complete the given task; intrinsic cognitive load therefore cannot be eliminated because it is essential to accomplishing the educational objective of the task to be performed.[123] Intrinsic cognitive load for a given task is determined by the number of interacting elements that must be stored and actively processed to complete it.[124] With simple tasks, the cognitive load may be small, but the intrinsic cognitive load can be considerable when engaging in complex cognitive tasks.[125] Complex tasks “impose[] a high intrinsic [working memory] load, that is, load that is directly relevant for performing and learning the task.”[126] Intrinsic cognitive load can be reduced by, among other things, scaffolding the information provided and tailoring the level of guidance to match the student’s level of expertise.[127]

Extraneous cognitive load, by contrast, is cognitive load that the learner experiences in the course of completing the task but is unnecessary to accomplish the learning objective and depletes resources in a way that hampers the student’s ability to learn.[128] Extraneous load is a form of extrinsic load and may be generated by aspects of the task as assigned, but it may also arise from aspects of the learning environment—or even the learner—that are not necessary to completing the task or acquiring the knowledge sought.[129] Eliminating, or at least reducing, extraneous cognitive load is one of the principal aims of instructional design.[130]

Germane cognitive load is cognitive load that is not strictly necessary to the narrow learning objective but that is beneficial to the student by enhancing the learning process or rendering learning more effective.[131] As construction and automation of conceptual schemas are the main features of the learning process, germane cognitive load can be understood as “the amount of [cognitive] resources devoted to the development and acquisition of schemas.”[132] Professors can aid students in the design of germane cognitive load by presenting information and learning materials, and designing learning activities, “in a way that promotes the development and automation of schemas.”[133]

One of the primary aims of applications of CLT in instructional design is to eliminate extraneous cognitive load so that the load involved in a given task is either intrinsic or germane.[134] And yet one of the principal challenges in this context is that different students facing the same assignment in a single instructional environment may experience the same features of that assignment in different ways. For one student, certain aspects may be experienced as intrinsic or germane cognitive load, while for others the same aspects may be experienced as extraneous cognitive load.[135] Even the same student may experience the same method or technique as different forms of cognitive load at different times.[136]

These three forms of cognitive load (intrinsic, extraneous, and germane) are present in a common task law students perform in a first-year legal writing course: preparing a case illustration. A case illustration is one of the most common components of various forms of written legal analysis, whether in internal memoranda, briefs, or judicial opinions.[137] In a case illustration, the writer summarizes a court’s decision, with particular emphasis on the court’s holding, its reasoning, and the key facts that the court articulated to support its conclusion regarding the issue at hand.[138] As a complex task, writing a case illustration is likely to generate considerable cognitive load, especially for a first-year law student.[139]

The task of composing a case illustration will certainly generate a certain amount of intrinsic (inherent) cognitive load: cognitive load that is imposed as a necessary concomitant of the educational objectives of the assignment. At a minimum, to complete the task a beginning law student will need to: (1) read (decode and interpret) the decision; (2) identify passages in the decision that contain pertinent information; (3) extract, modify, and/or convert the content of those passages to incorporate into a draft case illustration; (4) compose a series of prose sentences incorporating the extracted contents into a draft case illustration; and (5) edit and revise the draft to produce a final case illustration.[140] Each step of this process imposes considerable cognitive load, and yet this baseline load is necessary for the student to produce the required work product. None of these steps (except, perhaps, for step (5)) could be eliminated without derailing successful completion of the assignment.[141]

Extraneous cognitive load could be induced in the context of writing a case illustration in a variety of ways. One of the easiest ways for unnecessary (i.e., extraneous) load to be imposed would be for the student to try to skip or combine some of the above steps, thus increasing the need for parallel or simultaneous processing.[142] For instance, some students may try to simply read the decision, then set it aside and try to write a case illustration purely from memory. Doing so requires the student to keep a multitude of cognitive elements in working memory for simultaneous processing. This is a good example of how breaking a complex task into a series of process steps helps reduce extraneous cognitive load.

The professor can also generate extraneous cognitive load by complicating any of the five above steps, including by requiring the student to conduct research to identify and acquire the decision to be illustrated;[143] assigning a particularly complex decision that contains numerous nonrelevant passages;[144] providing insufficient guidance regarding commonly used techniques for modifying and converting case contents for use in a case illustration;[145] or providing insufficient guidance regarding the typical components and sequence of components contained within an effective case illustration.[146]

Germane cognitive load could be present in a case illustration in the beneficial difficulty—even struggle—that the student experiences in completing each of the five steps,[147] as this work involves application of a repeatable process that can be used anytime the student (or, in the future, the lawyer) confronts the common task of composing a case illustration. By repeatedly applying the steps of this process, the student gains skill in processing court decisions for incorporation into legal writing products the same way that a skilled fisher learns how to gut, clean, and filet fish. By setting up a highly structured, guided multi-step process, students can focus much of their effort on acquiring schemas that have multiple and repeated long-term applications, thus enhancing potential for skill transference. Effort that the students expend to increase their understanding of that particular case, about the legal issues raised by it, and about the law as a whole also represents features of germane cognitive load. Such learning typically includes familiarity with certain recurring patterns, which provide a further basis for development of schemas.

3. Cognitive Load in Complex Problem Solving

We may think of a 1L legal writing course as “basic.” But legal writing actually involves a wide array of complex cognitive tasks.[148] Assignments in legal writing courses also aim to help students develop skills in problem solving.[149] Complex problem-solving tasks generally are high in intrinsic cognitive load.[150] The types of problems involved in legal analysis tend to be highly complex, as a concomitant of making them authentic and therefore relevant to the realities of legal practice.[151] This authenticity can be desirable in legal writing courses because such problems are similar to those confronted by real-world lawyers and require the use of tools and approaches common to the practice of law.[152] On the other hand, having to complete complex problem-solving tasks causes a considerable increase in cognitive load, especially when those tasks are important and required to be completed under time pressures, as those in the legal context typically are.[153]

Legal writing problems are also “ill-structured,” in the parlance of cognitive scientists, meaning that they “have multiple valid solutions and solution paths,” rather than a single, well-defined “correct” solution.[154] Ill-structured problems tend to be particularly high in cognitive load.[155] The ill-structured nature of legal writing problems is not a defect; indeed, much of the value of such problems in training law students derives from this feature. Moreover, ill-structured problems tend to provide enhanced autonomy for students,[156] which—as discussed below—is advantageous.[157] And problem solving involving authentic and ill-structured problems also tends to be more engaging.[158] Simply put, all legal problem-solving scenarios will necessarily involve ill-structured problems, thereby increasing germane cognitive load.

Nevertheless, the additional cognitive load imposed by the sort of complex ill-structured problems germane to legal writing courses does present a major challenge to novice law students, and one that legal writing professors should be motivated to examine as part of the parameters of the design of their courses and assignments. Such problems tend to impose a high cognitive load on novice learners,[159] and reducing extraneous cognitive load is especially important for tasks that are high in intrinsic cognitive load.[160]

4. Methods for Counteracting Cognitive Limitations

CLT researchers have identified several methods, techniques, and approaches for alleviating the limitations of the interaction between working memory and long-term memory in the educational context. Below is an examination of several of the most important ones.

Isolation of Interacting Elements. Cognitive load increases whenever multiple elements need to be learned or processed simultaneously.[161] Thus, if the elements can be isolated and processed separately, then this will lessen cognitive load.[162] Using methods that enable students to engage in sequential processing of elements—including breaking up a task into subtasks—can reduce the effective cognitive load, thus enhancing the student’s capacity to learn.[163]

Integrated Sources. Based on what has been called the “split-attention effect,” having to switch attention between a number of separate sources imposes a higher cognitive load than when dealing with a single source.[164] Recognition of this effect tends to counsel in favor of providing students with a textbook or other integrated source as often as possible, rather than relying primarily on a series of independent handouts. Of course, educators often create individual handouts over the course of a semester when conducting in-class exercises, and this advice should not squash their freedom to experiment and develop new materials. A recommended practice would be, whenever possible, to collect such handouts into an organized binder or handbook.

Worked Examples. With a worked example, the student is provided with a problem and a step-by-step solution (or partial solution) of the problem.[165] “[N]ovice students learn more from studying worked examples that provide them with a solution than from solving the equivalent problems” on their own.[166] When students are asked to apply a problem-solving strategy, they typically must “use most of their [working memory] resources for applying the [] strategy,” leaving scant capacity within working memory to learn anything else.[167] The step-by-step solution demonstrated by a worked example lowers the extraneous cognitive load that the student experiences, freeing up working-memory resources to permit acquisition of the problem-solving strategy itself.[168] Thus, an effective approach in the context of working with novice learners in the acquisition of problem-solving skills is to include worked examples, especially when that particular strategy is first introduced.[169] This effect is even more pronounced with respect to the capacity of students subsequently to transfer the acquired knowledge or skills to a new context.[170]

Professors should be mindful of the timing within a course, however. Although worked examples can be very helpful to beginners, they actually can interfere with the learning process of more advanced students.[171] This is because students’ progress in acquiring proficiency is accompanied—and made possible—by the construction and development of conceptual schemas within long-term memory.[172] Once the student has available conceptual schemas to aid in the completion of the assigned task, introducing worked examples may increase their experienced cognitive load due to the interference between the examples and the preexisting schemas.[173] This interference is known as a “guidance-fading effect” and is similarly reflected in the recommendations typically given regarding the use of a “scaffolding” approach, in which over time the professor gradually reduces the use of directive guidance materials.

Collaboration. One of the most effective—and most often discussed—approaches for counteracting the limitations of working memory in educational settings is collaboration.[174] Through collaboration, each individual learner can draw upon the processing capacity of other members of a group to effectively increase the total available working-memory capabilities in acquiring knowledge and skills.[175] Indeed, the effect of collaboration in enhancing working-memory processing capabilities “can be considered as a single information-processing system consisting of multiple, limited [working memories] that can create a larger, more effective collective working space.”[176] Part of this expansion effect from collaboration results from the opportunity for individual learners to offload the cognitive load temporarily to some members of the group, thus freeing up working-memory resources of other members.[177] By sharing and alternating in this way—in a sense “sharing the load”—each member can learn more than they would have otherwise.[178] Collaboration can be especially effective when dealing with highly complex tasks.[179]

Physical Objects. The creation or use of physical objects to serve as temporary aids can decrease the effective cognitive load. This includes using models and diagrams, as well as gestures, such as counting on one’s fingers.[180] The key feature of this set of techniques appears to be the use of a physical object as an embodiment of an intangible concept, permitting demonstration of the relationships between the physical objects to illustrate the relationship of the concepts.[181] It may be that these methods are tapping into evolutionarily primary capacities.

Multi-Channel Communication. Researchers have identified at least two separate channels for delivery of information: visual and auditory.[182] Using the visual and auditory channels separately can reduce extrinsic cognitive load.[183] This includes using visual activities, such as color coding, to organize and present information.[184] One important point to note is that the simultaneous combination of visual and auditory information does, by itself, create additional cognitive load, as the student must engage in effort both to interpret and to coordinate the information contained in the two forms.[185] Moreover, it is crucial that the information provided in the two separate channels is separate but interdependent, rather than redundant.[186]

Motivation. The dynamics associated with cognitive load and the interactions of working memory and long-term memory for any given individual do not typically involve an absolute limit. There certainly are scenarios in which an assigned task exceeds the individual learner’s absolute working-memory capacity, thus resulting in a complete inability to complete the task. But in most situations, what the learner experiences is more relative and malleable. Cognitive load can be seen as a sort of burden that the individual can compare to the anticipated benefit expected to be gained from it in deciding whether the activity is worth the investment.[187] Although an increase in the individual’s motivation to engage in the activity cannot increase their underlying working-memory capacity, it can nevertheless render them more willing to expend the effort necessary to stick with the task at hand.[188] Cognitive load functions, in this way, as a drain on available resources; but the individual decides how much each is willing to invest.[189] This economics-oriented explanation of students’ experience of the effects of cognitive load is consistent with empirical research in other contexts, such as studies on mental fatigue.[190]

Of course, as discussed above in Part I.B.2, students can be motivated to expend the effort required to complete learning tasks in ways that either tend to support their autonomy or undermine it.

Learning Environment. The physical environment in which students are working can also greatly affect cognitive load. If the learning environment contains visual or auditory stimuli that are irrelevant to the task at hand, these stimuli may increase extraneous cognitive load by drawing students’ attention.[191] For example, posters, slogans, and other visual decorations in a classroom—no matter how well-intentioned—may create unnecessary burdens on students’ working-memory resources needed for task completion.[192] These effects may be especially acute to the extent that the stimuli tap into evolutionarily primary instincts and tendencies, such as tracking sudden movements or deciphering speech. Even the color scheme of the classroom or virtual learning environment may have a measurable effect on cognitive load, with the use of “bright, warm color combinations” associated with a positive emotional state that is conducive to managing cognitive load.[193]

Coping Techniques. Additionally, there are certain techniques students can use to help free up working-memory resources, such as taking a few moments periodically to close their eyes,[194] practicing mindfulness meditation, or engaging in a creative, expressive activity.[195] Because cognitive load is largely temporary, these sorts of techniques can provide effective relief to students, thus enabling them to return to their work with a greater capacity to focus on the task at hand.[196]

D. Charting a Middle Way: Cultivating Autonomy in Light of the Cognitive Limitations for Novice Learners

At this point, it is worthwhile to recognize the potential tension—if not outright conflict—between seeking to enhance students’ autonomy, on the one hand, and simultaneously seeking to reduce the cognitive load that they experience, on the other. At least at the conceptual level, the aim of cultivating autonomy tends to favor greater freedom, independence, and openness.[197] By contrast, the aim of reducing cognitive load—at least as an end in itself—tends to favor more direction, guidance, and restrictions, as well as a general preference for simpler and easier assignments.[198] Moreover, the critical role of decision-making within autonomy-oriented instruction creates further complications. Put simply, making decisions increases cognitive load and entails significant mental effort.[199] But decision-making is essential for developing autonomy,[200] especially in the context of the sort of complex problem solving increasingly required of beginning law students.[201]

What is needed, then, is a navigable middle way that seeks to harmonize and appropriately prioritize these two competing interests: cultivating autonomy on the one hand and reducing cognitive load on the other. I propose that between these two interests, cultivating autonomy should be recognized as the primary aim, with seeking to minimize unnecessary cognitive load as a secondary aim. The goal in a legal writing course should not be to eliminate the need to make decisions; rather, the goal is to facilitate and support the student’s exercise of autonomy in developing ever more skillful approaches to those decisions.[202]

As a starting point, it is helpful to remember that cognitive load is not simply an evil to be eliminated. A temporary increase in cognitive load is not inherently bad. Indeed, studies have indicated that such instances can have a positive effect on learning by, among other things, increasing vigilance on the part of the learner to overcome challenges, thereby enhancing information integration.[203] Additionally, overcoming challenges and even struggling (temporarily) is an important part of the skill-acquisition process.[204] Increased cognitive load also tends to make individuals more risk-averse, which could have the positive effect of steering a student away from unethical options such as plagiarizing and cheating.[205] Moreover, stress itself has been shown to have some positive effects on learning, at least temporarily, by increasing the learner’s focus.[206]

Nevertheless, there also appear to be numerous negative effects from increased cognitive load—especially in ways that are particularly problematic to the extent that one considers cultivation of autonomy to be an important educational objective. Even temporary increases in cognitive load negatively affect individuals’ capacity to make decisions in the short run.[207] Moreover, sustained levels of high cognitive load over time may have long-term effects on individuals’ decision-making abilities, not only in the form of stress and mental fatigue, but also by precipitating diminishment in the capacity for exercising executive functioning.[208] Increased cognitive load also reduces individuals’ capacity for empathy and prosocial behavior, both in the short term and over time.[209] The potential for long-term, sustained cognitive overload to harm individuals’ capacity to form and maintain close relationships is particularly troubling in light of the key role that relatedness plays in both educational performance and wellbeing.[210]

As discussed above, the key question when considering the cognitive load demands created in a particular educational context is whether the cognitive load being experienced by a given student in response to a particular task is positive (i.e., intrinsic or germane) vs. negative (extraneous).[211] Educators can and should eliminate (or reduce as much as possible) extraneous cognitive load and maximize the predominance of intrinsic cognitive load.[212] And my contention is that they should do so within an overall framework that is generally oriented toward the cultivation of autonomy, as part of a fundamental commitment to the overriding value of serving the wellness and wellbeing of students.[213]

An important guiding concept for navigating this middle way is the use of decision aids. When confronted with any learning task that involves decision-making, students generally tend to adapt their decision-making strategies so as to minimize their expenditure of effort.[214] Knowing this, the educator has a prime opportunity to shape student decisions by providing tools, materials, and instructions that are specifically geared toward aiding the student in making decisions.[215] By providing a decision aid to guide decision-making, the student perceives the use of the provided aid as likely to reduce the amount of effort needed to complete the task.[216] Decision aids are all the more important where the student experiences increased cognitive load, such as that involved in the sort of problem-solving exercises that are common in legal writing courses.[217] In such situations, students tend to adopt decision strategies based on eliminating possible solutions and become less receptive to additive strategies that focus on considering insights to be gained from combining available information.[218] By providing specifically tailored materials and instructional guidance, the educator can guide students toward selecting decision-making strategies that are normative and beneficial.[219]

II. What We Can Do: Implementing a Guided Autonomy Approach to Legal Writing

Legal writing courses present a prime opportunity within the law school curriculum to cultivate autonomy. The focus of these courses is typically the independent development of a tangible work product over time, rather than completing a timed response to an examination prompt imposed on the student.[220] Legal writing courses also provide an opportunity to emphasize project-management and time-management skills and high-level executive decision-making.[221] And these courses typically involve a heightened role for one-on-one feedback and instruction, as well as greater freedom on the part of students to select strategic approaches and make decisions about the specific direction and content of their research, arguments, and analysis.[222] Legal writing courses are also heavily focused on realistic practice-oriented problem solving.[223] Thus, legal writing courses offer opportunities for creative choices and the encouragement and exercise of the students’ developing professional judgment.[224]

A. Some Guiding Principles for Implementing Autonomy-Supportive Approaches to Legal Problem Solving

When we teach students about writing, we also inevitably convey our understanding of what writing is, how it functions, and how we relate to it.[225] So the starting point for implementing a guided autonomy approach in the teaching of legal writing is to allow the insights gained from the empirical research discussed above to inform our understanding of the opportunities that legal writing can offer to students in their development as professional solvers of legal problems.

One of the keys to this enhanced understanding is to refresh our model for how thinking and writing interact within the context of legal problem solving. Although instrumentalism was largely jettisoned as a guiding model decades ago, remnants of this model remain and inform a prevailing view—at least among students—in which writing is seen as the product of thinking, such that one must rehearse a series of thoughts in the mind first, which one then records in writing.[226] In this view, the writer functions as a sort of transcriptionist of a series of thoughts.[227] Adherents of this view generally propose that one must think something first before it can be written, with the obvious conclusion becoming that if one wants to improve their writing, one should focus on improving their thinking.[228]

But this popular view of writing—which we might call a latent instrumentalism—is at odds with empirical findings and with a careful examination of the processes and activities of legal writers in practice. A more accurate model recognizes that writing includes a variety of techniques, processes, and activities to construct physically embodied structures that aid thinking and, in particular, by alleviating the difficulties created by the severe limitations of our active-processing cognitive architecture.[229] Although humans are pretty good at simple thinking tasks with limited simultaneous processing (such as, for instance, recognizing simple patterns, finding differences and similarities in form among a limited number of options, and following an order to complete a single task), we struggle with complex tasks that include a variety of different processes simultaneously, such as those that a legal writer will confront.[230] Skillful problem solvers use writing to construct various forms of scaffolding for themselves so as to overcome the challenges of cognitive load as they engage in complex problem solving.[231] A simplified understanding of this dynamic is that writers—specifically, legal writers—use writing to create tools that they then implement to solve problems.[232] And they also use writing to create organized summaries of their solutions to those problems, which is the typical form that a final, formal legal analysis takes.[233] In this way, we start to see legal writing as a set of techniques, methods, and processes that relate to thinking, giving shape to it, providing structures for it to inhabit, testing and developing it so that a series of solutions can be born and introduced to readers.[234] The more legal writing professors understand these features, the better they will be able to guide their students in the acquisition and development of skills necessary to engage in these activities successfully.[235]

Another important feature of this enhanced understanding is to fully appreciate the nature of three important writing-based steps in legal problem solving: (1) problem design or representation; (2) generating and developing solutions; and (3) solution presentation (which includes providing justifications and construction of arguments).[236] A skillful legal writer recognizes the importance of each of these steps and knows how to use available tools and techniques to accomplish each.

Problem Design/Representation. The critical importance of the first step, problem design, cannot be overstated. As noted above, legal analysis problems are ill-structured, in part because they lack a clearly defined initial problem state.[237] And this feature of legal problem solving cannot be eliminated without jeopardizing the most important skill a legal analyst can possess: problem design.[238] The reductive term “issue-spotting” is oversimplified, but its central role in legal education and assessment indicates the importance of this skill.[239] What a first-year law student must learn, more than anything else, is how to design and construct valid initial problem spaces to give clarity about the nature of the initial problem state, so that they can subsequently construct (and finally summarize) a valid solution.[240] Teaching students how to do so therefore provides one of the most critical, foundational educational objectives of a first-year legal writing course.[241] Problem design extends beyond merely formulating an effective issue statement. Knowing the form of valid solutions informs the design of initial problem spaces based on an understanding of the problem presented.[242] For example, having an understanding of the role and importance of the key components of a standard legal analysis (issue statement or conclusion; rule summary; case illustrations; and application) helps guide the student to identify and select elements from the available sources for processing and assembly.

Incoming law students tend to be open to the idea of solving problems. But they are often reluctant to take on the role of creating or designing problems to be solved. They are typically accustomed to being presented with well-structured problems with preset and narrowly defined initial problem states.[243] They find it very difficult (and often counterintuitive) to begin by purposefully designing and constructing the problem to be solved. And their resistance is increased due to the inherent uncertainty in legal analysis, as there is no single “correct” initial problem state.[244] Instead, what they find, inevitably, is a multiplicity of potentially valid initial problem spaces to construct.[245] These difficulties are exacerbated by the fact that the novice student does not begin by knowing what the criteria for validity even are, and learning those criteria is gained over time by solving legal problems and seeing how others have solved similar problems in prior cases—a classic chicken-versus-egg dilemma.[246] On top of this, the legal analyst’s understanding of the problem to be solved—in simplistic terms, the “issue”—evolves as they modify, develop, or even rework the working solution in the second step (problem solution).[247] So although the first and second steps involve separate cognitive steps, the analyst will typically move back and forth between these two steps again and again as a working draft is developed.[248]

Generating/Developing Solutions. In the second step, the legal analyst attempts to solve the problem as provisionally designed or represented in the first step by developing an appropriate solution.[249] The default approach in this step is trial-and-error, as the analyst tries a number of different possible moves in converting the initial problem state into a valid solution.[250] Trial-and-error is the least efficient approach to problem solving, but it is the approach a novice student is most likely to take because such a student is less familiar with the various sorts of moves that are germane to legal analysis.[251] Someone who has no alternative to a trial-and-error approach is also susceptible to giving up and terminating any further effort before a solution can be reached, as they are likely to conclude (and often rationally so) that the cost of expending the effort required is excessive as either a solution cannot be obtained quickly enough, or the perceived value of obtaining a solution is not deemed worth the required effort. Students who face this situation are likely to question the value of the assignment and blame the professor for poor instructional design.

The inherent uncertainty and indeterminacy of legal problem solving precludes complete elimination of the role of trial and error. Moreover, increasingly empirical research suggests an important educational value in designing a certain degree of struggle in problem-solving assignments.[252] When a student must struggle to find a solution to a problem, they activate and prime certain structures within the brain that are important for long-term acquisition and retention of skill-related knowledge.[253] But that struggle need not be endless and completely open-ended. Professors can and should provide guidance to novice students with respect to this step, by providing materials, instruction, and exercises that preserve the autonomy-oriented role of decision-making while providing decision aids that alleviate the negative aspects of cognitive limitations.

Interventions in guiding students in the second step (solution generation and development) focus on providing opportunities to learn the typical forms that solutions to legal problems take, the most common moves that analysts make in constructing those solutions, and the features and attributes of those moves. In doing so, we also begin to familiarize students with the validity criteria for evaluating proposed legal solutions. Templates for each of the three primary components of most standard legal analyses (rule summaries; case illustrations; and applications) can provide the students with an off-the-rack scheme for organizing information, which the student fills in. Having a pre-determined set of component categories aids the student in identifying pertinent content from the available sources.[254] A template can also guide the student in understanding the network of relationships between those contents and how individual components interact. For example, the Rule Summary Template (Appendix A) sets out a typical sequence of sentences in a rule summary paragraph that guides students in constructing a framework for elucidating the core concepts and their logical relationships in summarizing the applicable governing legal principles for a legal memorandum or brief. Preset forms, such as the Case Illustration Form (Appendix E), can also help guide students in identifying and collecting the contents needed to fill in the template from the available sources.

Solution Presentation. In the third and final step, solution presentation, the legal analyst takes a step back from the solution of the problem and purposefully constructs an organized summary of the problem and the steps of the solution, along with justifications and arguments in defense of the solution, so that the reader can understand how the solution was derived without having to do the work of providing their own solution.[255] Analogies to this step include providing a guided tour of a building and composing a walkthrough for a puzzle or video game.[256]

This step is not particularly difficult in itself. In fact, most people are familiar with the core techniques involved in providing a step-by-step summary in a variety of contexts.[257] The difficulty arises due to two separate factors. First, the effectiveness of this step depends on the two prior steps. It is impossible to provide a logical, coherent, and valid summary of a solution if the initial problem state and the subsequent solution are not properly constructed. Second, beginning students often do not think that there is even a need to engage in the third step (composing a summary of the solution separate from simply solving the problem), based on the mistaken assumption that the reader can understand the solution the student has found, simply by their having perceived a solution through the work they performed in completing the second step.

In other words, they are mistaking a tool for a component: The writing they produced may have been an effective tool for reaching a solution, but that does not mean that what that writing contains provides an effective walkthrough of that solution for the reader. One of the most common complaints about law students’ legal writing is that they fail to show all the steps of their reasoning.[258] But many students simply cannot see how this criticism relates to their work because the writing that they produced was the vehicle for their solution to the problem.[259] The disconnect here is failing to see how writing can be used in two separate ways: first as a means of arriving at a solution, and then second as a means of constructing an organized tour through the path leading to the solution. Novice legal writing students typically engage in writing that enables them to understand how the problem can be solved, and what they turn in as a final product is simply what they wrote in order to understand that solution.[260]

Beginning students also often neglect the third step out of a misguided deference to the expertise of the reader; they are afraid of talking down to the reader and over-explaining solutions. This makes the student more likely to assume that if what they wrote in the second step was sufficient for them to understand the solution, it will also be sufficient for the more sophisticated and knowledgeable reader to reach the same solution.

A final guiding principle is to understand the critical role of decision-making in legal writing. Even though decision-making imposes a high cognitive load—thus, it might appear to be a prime target for cognitive load reduction—this aspect of the learning objectives and context is too important to cut. Autonomy necessarily requires active, volitional decision-making. If the student perceives the decision as forced, this undermines the student’s progression along the motivational continuum toward intrinsic motivation.[261]

Understandably, it can be tempting for professors to protect students from having to make decisions by simply providing them with a comprehensive set of step-by-step instructions. Students will generally appreciate such instructions, in part because many of them are accustomed to receiving them from prior educational contexts. But such instructions take all decision-making away from the student, perhaps because the professor does not trust the student to be able to make decisions.

Now, there is certainly a place for judicious use of step-by-step instructions for some tasks in some contexts—most importantly, when breaking up complex, multistep skills into subtasks.[262] But the wholesale use of this approach prevents students from developing skills in decision-making and undermines the cultivation of autonomy. In such an environment, students may learn how to follow instructions (or obey commands), but they are not learning how to make the sorts of decisions that are critical for developing skill as a professional and independent legal problem solver. As an analogy, one does not become a skilled chef simply by learning how to follow a set of recipes.

Nevertheless, recognizing the cognitive limitations confronting novice legal writing students, we can guide students in the development of their decision-making capacities. The mute blinking cursor can be replaced by a menu of options, along with a set of tools. And we can give students opportunities to practice using those tools in pre-planned exercises. As we do so, we can keep in mind the aim of creating and preserving opportunities for students to recognize decision points: instances in which they have a decision to make. The goal is for students to increase their awareness of available options and decisions to be made. And that growth is supported, not thwarted, by giving them decision aids—materials and tools that guide the decision-making process.

B. Recommendations for Implementing Guided Autonomy Approaches in Law School Courses

Although “[a]pplying autonomy support is as much an attitude shift as it is a teaching technique,”[263] there is value in being able to consider some concrete options, tools, methods, and suggestions for cultivating autonomy in legal writing courses, especially in light of the cognitive limitations that are so prominent among first-year law students. What follows is by no means intended to provide a comprehensive list of potential techniques and methods, as it certainly remains true that “faculty members must develop their own individual strategies, upon reflection of their own teaching practices, and pedagogical goals.”[264] Moreover, these recommendations only reflect one professor’s efforts to implement lessons and principles derived from the available findings; they have not been subjected to rigorous empirical testing to evaluate their effectiveness—a deficiency that hopefully will be remedied by future research efforts.

Communication Style. One of the most important contributing factors in cultivating autonomy is the professor’s style of communication.[265] This includes not only the informational content of communications but also the specific words chosen, the professor’s attitude, and the tone in which messages are delivered.[266] The professor should emphasize students’ freedom and the availability of choices, rather than emphasizing requirements.[267] The goal should be to convey respect, rather than exert control.[268] Moreover, an autonomy-supportive style acknowledges students’ feelings, including their expectations and frustrations.[269] A further aim is to encourage students to engage in cost-benefit analyses regarding assignments and to be proactive in planning and tracking their work, which can be guided by providing them with forms or other materials to plan out timelines for completing assignments.[270] It is also advisable to talk openly about cultivation of autonomy as the express aim of the coursework: discuss the empirical research as an important basis for the design of the course and its assignments and invite students to contribute to the development of the course based on their experiences. This reinforces students’ perception of their own agency, and it also encourages them to see the importance of scholarship as part of the educational focus of a university. These elements of an autonomy-supportive communication style are consistent with students’ development of metacognitive capacities, which further benefits their academic performance.[271]